The ubiquity of the digital image

Introduction

As a photographer, I have been wondering how many pictures exist with me in them, standing somewhere in the background, that were taken by random strangers. There must be a lot of pictures like this, photos taken in public by others, accidentally capturing oblivious passers-by together with an intentional subject. My curiosity brought me to the website pimeyes.com. This site claims that they can find any face you are looking for on the Internet with the help of facial recognition software combined with the power of machine learning.[1] I did not feel very comfortable with uploading a picture of myself to this strange site. However, curiosity won again. To be honest, we are uploading images of our faces all the time, but perhaps the password of our personal social media account gives us a false sense of security. I uploaded my self-portrait, and in a second I had hundreds of matches. There were many pictures of people with similar facial features to my own, but not my own image – except for one, and only one, match, a picture of me from maybe 5 years ago which I cannot remember being taken. This photograph depicted me with two other people who were both very familiar to me. But that was it. The link to the picture couldn’t be retrieved, since this feature is for paying customers only. I can’t be certain where the picture is shown online, even if I have my suspicions.

It is an indisputable fact that photography has been through significant changes in the last 25 years. The image has moved mainly into the virtual realm where the main means of experiencing it by humans is via a screen. The camera has become a ubiquitous part of every smartphone, thus it’s available to everyone now, and not just enthusiastic individuals. This ubiquity of the camera is the main reason we are taking more pictures than ever before. According to Fred Ritchin, in 2013 more photographs were produced every two minutes than were made in the entire nineteenth century.[2],[3] The analytical portal Statista.com states that in 2013, when Ritchin’s text was published, the estimated amount of produced photographs settled at 660 billion. Four years later in 2017, it was estimated that this number had almost doubled, and 85% of photographs were taken by mobile phones.[4] If this trend persists, the number of images taken now in 2020 will be even higher; and we would then speak about trillions of images, such an abstract amount we can hardly imagine it.

The way in which we experience the majority of photographs today has changed, too. We see a large number of images on device screens, one after another. The time spent with each image is minimal, thus images are perceived more cinematically nowadays. Images are usually put in a virtual queue, similar to the physical film strip, and through the quick changing of images on a screen we put the virtual queue in motion, thereby creating a cinematic experience of viewing for ourselves.

Images made by and for machines

From the machine point of view, there is no difference between the text, image, video or any other digital file, and likewise any data.[5] The file can be analysed without the necessity of converting such data to a human-readable format. This possibility of machine interaction opens the door for a new form of surveillance. This ‘automation of vision’ allows analysing data on an ‘enormous scale and, along with it, the exercise of power on dramatically larger and smaller scales than have ever been possible’.[6]

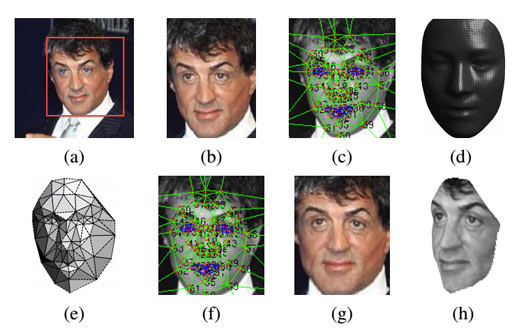

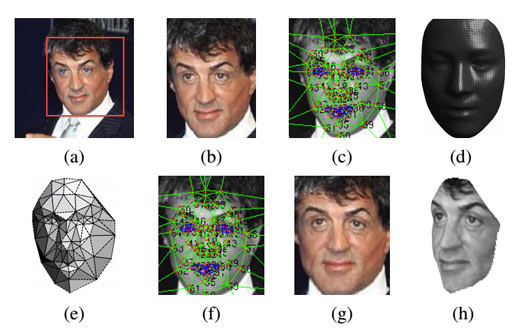

Trevor Paglen, in his article Invisible Images (2016) highlights that, on the surface visible level, there is not much difference between showing photographs in physical photo albums and the holiday pictures we share on social media; however, what makes online viewing of images significantly different is the invisible background algorithm. We are feeding an array of powerful artificial intelligence systems, which are learning how to identify people, places, objects and habits etc., regardless of whether actual humans see any of this data. For example, Facebook deployed its DeepFace (Fig. 1)

algorithm in 2014 that achieves over 97 percent accuracy in identifying individuals. This percentage is comparable to what a human can achieve – but no human can recall the faces of billions of people.[7] The main principle of this algorithm resides in building 3D models of faces from the photographs. Subsequently, it corrects the angle of the face, so that the person in the picture faces forward, and then puts a mathematical model of the face into a neural network which compares the model with other images. If the algorithm finds a similarity between images, it decides that it must be a match[8]. This neural network mimics the way the human brain operates – thus, it’s teaching itself. The more data we provide, the more accurate it becomes.[9]

The proliferation of digital images on social media, and other data, has caused the world wide web to, as Ritchin suggests, ‘become a form of consumerism wherein reports on contemporary events become easily overlooked items on the menu of choice’,[10] because viewers are able to access any data without ‘hierarchy of importance’.[11] This situation has also created a territory for a new form of censorship. In the past, censorship worked by blocking and deleting information. In the 21st century, censorship operates by flooding people with irrelevant information and data, in which it is hard to orient oneself and to know what to pay attention to. People also often spend time investigating and discussing side issues. Having power today means knowing what data to ignore as opposed to the past, when power meant having access to data.[12]

Image as a commodity

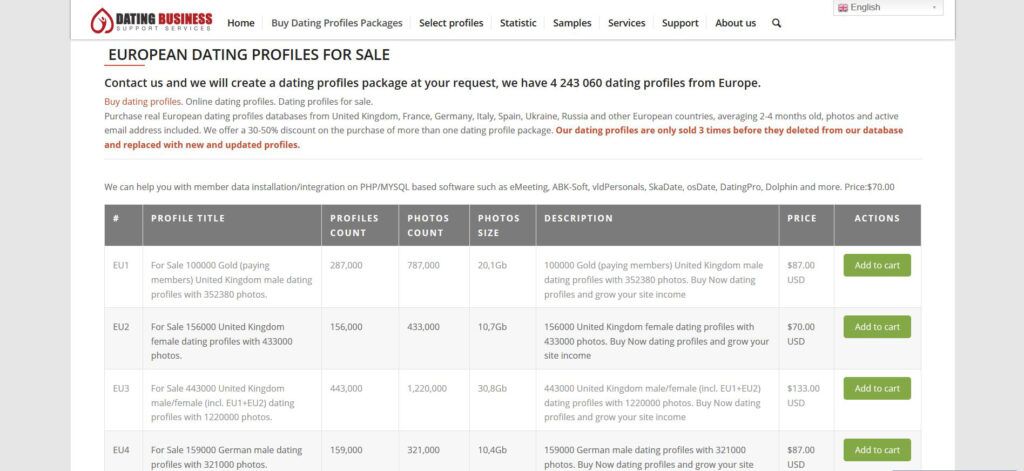

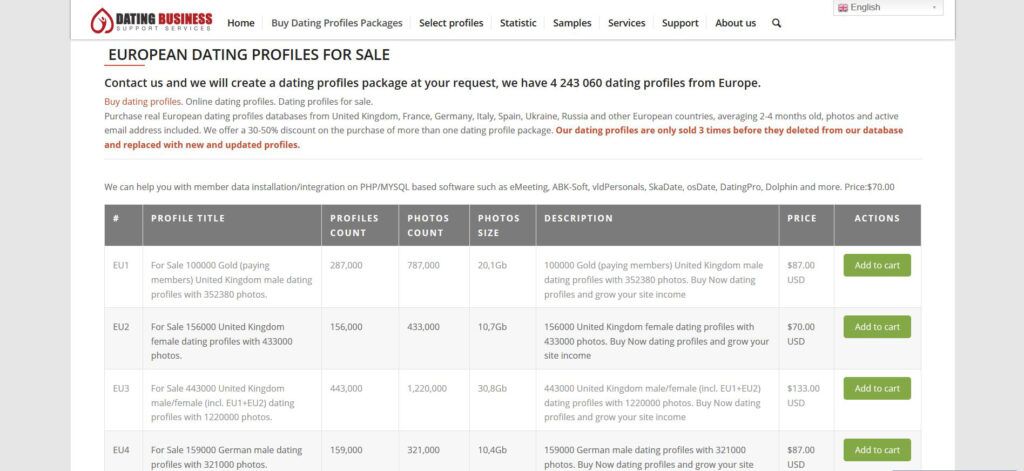

In May 2017, Berlin and Barcelona based artist Joana Moll worked with Tactical Tech, an international non-governmental organisation that engages with citizens and civil-society organisations to explore and mitigate the impacts of technology on society,[13] to legally purchase one million dating profiles for €136 from a US-based company, which trades profiles from dating sites all over the globe (Fig. 2).

The purchased profiles contained nearly five million pictures together with private information about users who had created profiles, such as, email addresses, sexual orientations, nationalities, interests, professions, and other detailed personal information. Joana Moll’s project The Dating Brokers: An Autopsy of Online Love is making visible the vast network of companies capitalising on this information from dating profiles without the conscious consent of users, who are being exploited. Companies are using these purchased profiles to populate their new dating sites with faces, increase matchmaking possibilities and eventually attract new paying users. One of many companies who are involved in the trade is US-based Match Group Inc., who have in their portfolio dating sites such as Tinder and Plenty of Fish. [14] Through the pictures from those exploited dating profiles and also a paradigm of social networks where people are able to upload an almost unlimited number of self-representations, our faces are getting disconnected from our physical bodies.[15] As Hito Steyerl proposes:

‘[Our] face is now an element – a face/ mixed_with_phone, ready to be combined with any other item in the library. Captions are added, or textures, if needs be. Face prints are taken. An image becomes less of a representation than a proxy, a mercenary of appearance, a floating texture-surface-commodity.’[16]

Stolen or sold images from dating sites can be used to humanise social media chat-bots. Proxies, who are scripted to act like real humans, are wearing a person’s face, distorting discussions by spamming them with advertisements and picturesque images of tourist destinations, and they can be operated by political parties to enforce their interests.[17] Pictures used for these bots become quite autonomous, active, even militant.[18]

Another example of images as a commodity could be the case of Vigilant Solution. Vigilant Solution is a US-based company that has billions of vehicle locations captured by ALPR (Automatic License Plate Recognition) systems in their database. ALPR is a technology that allows law enforcement and private companies to track the travel patterns of drivers through networks of cameras that record license plates, along with the time, date and location.[19] In January 2016, Vigilant Solution signed contracts with local Texas governments. The company provided the ALPR system for their police cars and gave them access to their own vehicle database. As a return, the local governments provided Vigilant with the records of outstanding arrest warrants or overdue court fees which had been uploaded into their database. When the ALPR system on the police car spots a suspicious vehicle, the police officer pulls the car over and gives the driver two options: they can pay an outstanding fee on the spot with a 25% surcharge, which goes to Vigilant, or they will be arrested. The main controversy, in this case, is that Vigilant keeps every license plate reading from the police ALPR system together with other provided personal data, which can be capitalised on in other ways.[20] This case is a great example of machines making pictures for another machine, and also an example of surveillance on a mass scale.

Photography has gone through a major evolution since the invention of digital image and easily accessible digital cameras. The unfolding of the commodification of digital images at the end of the second decade of the 21st century is just one example of many. When new digital technologies began prevailing in the 1990s, it was difficult to predict what photography would become in 30 years. Critics in the 1990s saw the new digital technology as the death of the photograph and developed the discourse in two directions: apocalyptic on the one hand, and euphoric on the other. Also, some critics argued that images made up of ‘manipulatable code would no longer carry reliable traces of the visible world’.[21] Fred Ritchin, in his essay The end of photography as we have known it, published in 1991,expressed his concerns around the possibility of a change to photography on a professional and also personal level. He argued that with the help of a personal computer, one can easily be placed in front of the Eiffel Tower without having to leave home, or modify other personally important events.[22] Ritchin was concerned that family albums will show how people wanted to look instead of how they really looked in the moment at which the photograph was made. He also stated his fears that this manipulation ‘will further degrade the reliability of the documentary photograph for the public’.[23] Martha Rosler argued in her essay, Post-Documentary, Post-Photography? originally published in 1999, that ‘the status of the photographic image as a faithful representation of sheer visuality [was] radically impeached by the wide availability of computer programs that easily manipulate and alter the image’.[24] However, it could be arguedthat photographs have always been subject to the photographer’s agenda. Editing, falsification and manual retouching of photographs for idealisation or political propaganda were always prevalent in the photographic analogue realm.[25]

On one hand, we have what is described as an indisputable technological shift in photography in the last 30 years, where photography has become ubiquitous. But today in 2020, we still tend to trust that photographs are, to some degree, a representation of reality. Images made for photographic identification (such as passport photos, for example)[26] or surveillance prove this claim. On the other hand, it is difficult for us now to visualise and consider what will happen in the future with more advanced surveillance algorithms and VR technologies, augmented reality, 3D printing and realistic images constructed by artificial intelligence. We can only speculate, just as we speculated in the last decade of the 20th century when visual culture went through one of the biggest technological revolutions since 1839. But it is worth considering what we learned in the past three decades, and cautiously refrain from overly catastrophic or extremely positive thinking, and try to keep all speculative ideas unbiased.

References:

Chen, J., ‘Neural Network’, Investopedia, 13 Oct 2019, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/n/neuralnetwork.asp (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

Dubois, P., ‘Trace-Image to Fiction-Image: The Unfolding of Theories of Photography from the ‘80s to the Present’ October, 158, Fall 2016.

Flusser, V., Towards a Philosophy of Photography, London, Reaktion Books, 2000.

Harari, Y.N., Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, London: Harper Collins, 2016, Available from E-Book Library, (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

Maass, D., ‘Here’s Why You Can’t Trust What Cops and Companies Claim About Automated License Plate Readers’, Electronic Frontier Foundation, 19 Mar 2019, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/03/heres-why-you-cant-trust-what-cops-and-companies-claim-about-automated-license (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

Moll, J., The Dating Brokers: An autopsy of online love, https://datadating.tacticaltech.org/viz (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

Paglen, T., ‘Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You)’, The New Inquiry, 8 December 2016, https://thenewinquiry.com/invisible-images-your-pictures-are-looking-at-you/ (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

Pedersen, H., ‘Communities Across the Country Reject Automated License Plate Readers’, Electronic Frontier Foundation, 21 Aug 2019, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/08/communities-across-country-reject-automated-license-plate-readers (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

Richter, F., ‘Smartphones Cause Photography Boom’, https://www.statista.com/chart/10913/number-of-photos-taken-worldwide/, 2017, (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

Ritchin, F., Bending the Frame, New York: Aperture, 2013.

Ritchin, F., ‘The end of photography as we have known it’ in Wombell, P., PhotoVideo: Photography in the age of the computer, London: River Oram Press, 1991.

Rosler, M., Post-Documentary, Post-Photography? in M. Rosler (ed.) Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings, 1975-2001, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004.

Simonite, T. ‘Facebook Creates Software That Matches Faces Almost as Well as You Do’, MIT Technology Review, 17 March 2014, https://www.technologyreview.com/s/525586/facebook-creates-software-that-matches-faces-almost-as-well-as-you-do/ (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

Soutter, L., Why Art Photography, New York: Routledge, 2013.

Steyerl, H., ‘Proxy Politics: Signal and Noise’, E-flux journal #60, December 2014, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/60/61045/proxy-politics-signal-and-noise/ (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

Weibel, P., ‘Photography and the Administration of Data’ in Hasselblad Foundation, Watched!, Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2016.

List of images:

Figure 1: Head Turn, 2014, https://www.technologyreview.com/s/525586/facebook-creates-software-that-matches-faces-almost-as-well-as-you-do/(accessed 2 Apr 2020).

Figure 2: usdate.org, an example of the available packages of profiles for sale, screenshot

https://www.usdate.org/product-category/european (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

Websites:

https://pimeyes.com/en/faq (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

‘Artist Erik Kessels unveils 24 hour photo installation’ https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-15756616 (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

[1] https://pimeyes.com/en/faq (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

[2] F. Ritchin, Bending the Frame, New York: Aperture, 2013, p.28.

[3] ‘Artist Erik Kessels unveils 24 hour photo installation’ https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-15756616 (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

[4] F. Richter, ‘Smartphones Cause Photography Boom’, https://www.statista.com/chart/10913/number-of-photos-taken-worldwide/ ,2017, (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

[5] P. Dubois, ‘Trace-Image to Fiction-Image’, October, No. 158, Fall 2016, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2016,

p. 159.

[6] T. Paglen, ‘Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You)’, The New Inquiry, 8 December 2016, https://thenewinquiry.com/invisible-images-your-pictures-are-looking-at-you/ (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

[7] Ibid. 6

[8] T. Simonite, ‘Facebook Creates Software That Matches Faces Almost as Well as You Do’, MIT Technology review, 17 March 2014, https://www.technologyreview.com/s/525586/facebook-creates-software-that-matches-faces-almost-as-well-as-you-do/ (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

[9] J. Chen, ‘Neural Network’, Investopedia, 13 Oct 2019, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/n/neuralnetwork.asp (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

[10] F. Ritchin, Bending the Frame, New York: Aperture, 2013, p.28.

[11] Ibid, p.30

[12] Y.N. Harari, Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, London: Harper Collins, 2016, p.326, Available from: E-Book Library, (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

[13] https://www.tacticaltech.org/#/about

[14] J. Moll, The Dating Brokers: An autopsy of online love https://datadating.tacticaltech.org/viz (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

[15] H. Steyerl, ‘Proxy Politics: Signal and Noise’ , E-flux journal #60, December 2014, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/60/61045/proxy-politics-signal-and-noise/ (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

[16] Ibid. 15

[17] Note: Proxy is the agency, function, or power of a person authorized to act as the deputy or substitute for another , https://www.dictionary.com/browse/proxy?s=t (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

[18] H. Steyerl, ‘Proxy Politics: Signal and Noise’ , E-flux journal #60, December 2014, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/60/61045/proxy-politics-signal-and-noise/ (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

[19] D. Maass, ‘Here’s Why You Can’t Trust What Cops and Companies Claim About Automated License Plate Readers’, Electronic Frontier Foundation, 19 Mar 2019, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/03/heres-why-you-cant-trust-what-cops-and-companies-claim-about-automated-license (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

[20] T. Paglen, ‘Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You)’, The New Inquiry, 8 December 2016, https://thenewinquiry.com/invisible-images-your-pictures-are-looking-at-you/ (accessed 2 Apr 2020).

[21] L. Soutter, Why Art Photography, New York: Routledge, 2013, p. 93.

[22] F. Ritchin, ‘The end of photography as we have known it’ in P. Wombell, PhotoVideo: Photography in the age of the computer, London: River Oram Press, 1991, p.13.

[23] Ibid. 22, p.14.

[24] M. Rosler, ‘Post-Documentary, Post-Photography?’ in M. Rosler (ed.) Decoys and Disruptions: Selected writings, 1975-2001, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004, p.210.

[26] P. Weibel, ‘Photography and the Administration of Data’ in Hasselblad Foundation, Watched!, Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2016, p.235.