A History of Haunting

On the edge of a family history in Iceland exists a story about a man named Haraldur Hamar. As time moves on this story becomes more and more mysterious as if the facts seem to be slowly turning into fiction and with each piece of information found that more incredible his story becomes. Haraldur was born in 1892 in Reykjavík, the son of a respected poet and Haraldur decided early on to follow in his father’s footsteps. Around the same time as WWI begins, Haraldur moved to London. Perhaps he wanted bigger things than Iceland could offer, or maybe he did not believe he would have the opportunity to fully be himself if he stayed.

“Life is bright and beautiful, and the hardships are also fun, if they don’t ride you to hell. I have started to engage with real life, and we can’t know how our offspring will be.”

His story exists in fragments here and there, in archives, tall tales and rumours. Eventually it became the subject of my artistic work ‘I saw three suns in the sky’. I see Haraldur as a collaborator and his writings inspires me. He was a poet and dramatist, a bohemian and a dreamer. He wrote plays, though none were performed and only one still exist: Sancta Sanna. He concidered it his masterpiece and is said to have carried it around wherever he went. According to his friends Sancta Sanna was a play only meant for reading. Another play he wrote was lost to time, but was said to be too strange and Scandinavian to ever reach a stage in England. Some might want to call him a failed artist, some indeed have, but he never seems to have lost faith in his talents. Reading between the lines you could guess that there was more to his “failure”.

“My mind wonders, and then many will occupy it, and they dance longer than I can endure. The talents I possess must fight the fame of my forefathers, as is normal. But I shall have victory, and like the storm I will brush through the mountaintops. I will carry victory to all the talents I possess.”

Because his story is fragmented and filled with gaps, in a way his presence became stronger. He exists between the lines, and I have been able to create my own vision of his life through my reading of his words. The starting point for my work was going through archives and family documents. I visited sites that hold physical records like the archive in The National Library of Iceland but what existed there was incomplete. I realised that Haraldur exists both inside and outside of the archive. His name has floated around in conversations between people and was kept alive with rumours and stories. People who remembered seeing him in his later years could not or would not say precisely why he was never successful as an artist. When asked, they described feeling sorrowful that such a talented man never achieved his dreams.

“I am hoping that I will get on a plane soon and I look forward to it. But don’t mention it to anybody, because mom might get scared that I will fall, but if I fall, I will fall up, not down.”

It is a search for a man long gone, carried out by talking to people that might have met him or seen him, writing down rumours, asking around in the family and using a clairvoyant to reach Haraldur in the afterlife. All of this information that I gathered is what can be discussed and labeled as a figurative archive. The figurative archive concerns itself with information that is not found in, or is overlooked by literal archives. By literal archives, I am referring to places and institutions that hold physical records. The figurative archive consists of knowledge and information that is more difficult to grasp, like memory and rumours. Often it is the knowledge and information that does not exist in physical form and will not follow the rules of the literal archive. Making this distinction within the archive is something that Ernst Van Alphen, a professor in literary studies, considers when discussing archival artists that often work with and highlight information that literal archives have left out. (1) Van Alphen draws on Michel Foucault’s notion that the archive is a term for what can be said and what can not be said. By using the term archive we have already incorporated a set of rules that without maybe realising it, involves certain exclusion of material and knowledge.

“The moon is shining and the sky is clear. The trees are mirrored in the water and the swans swim on silver ripples. I sit here alone by the window and my mind travels home, over the ocean, to my fathers grave. I cry there for a short while.”

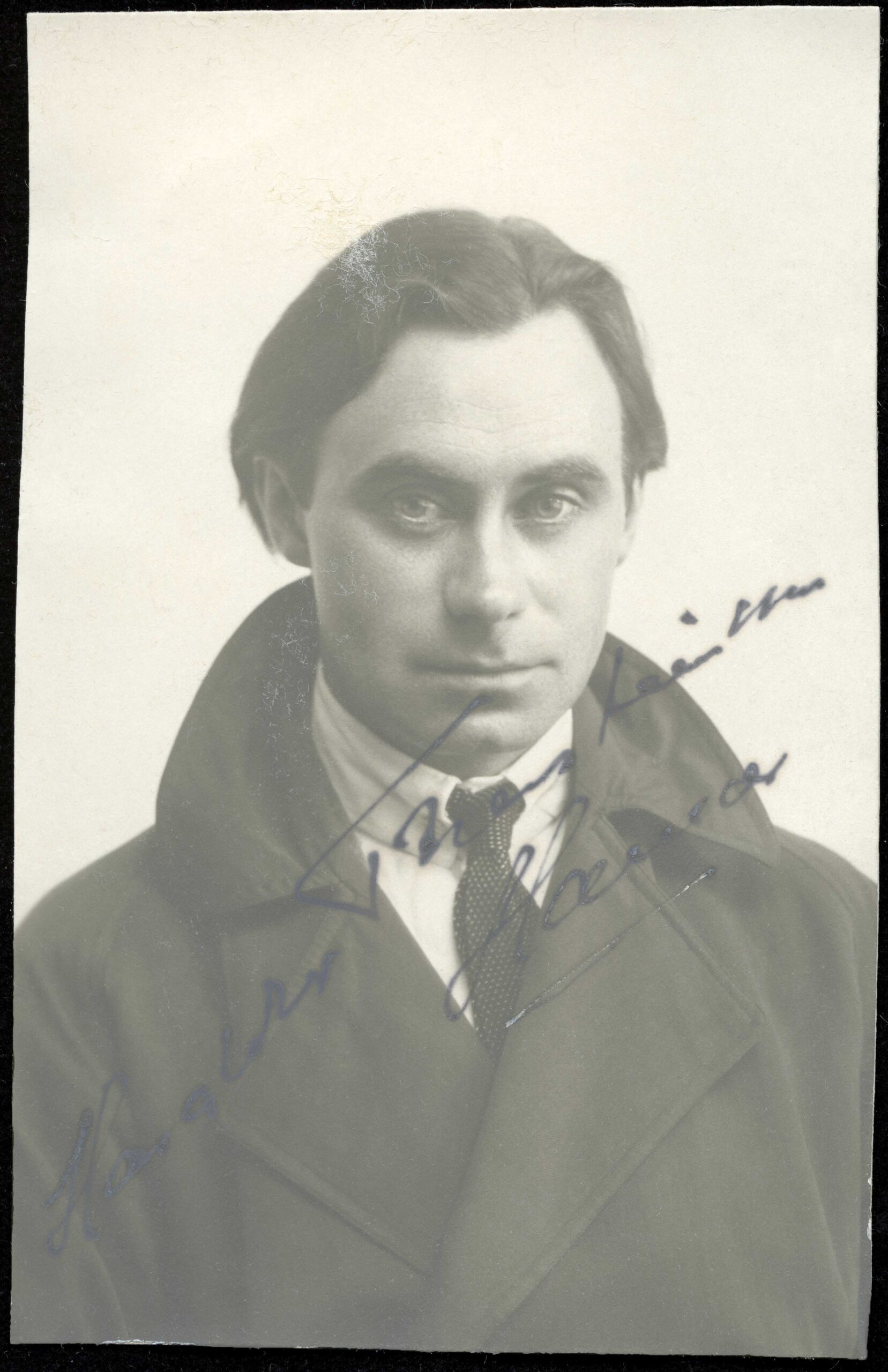

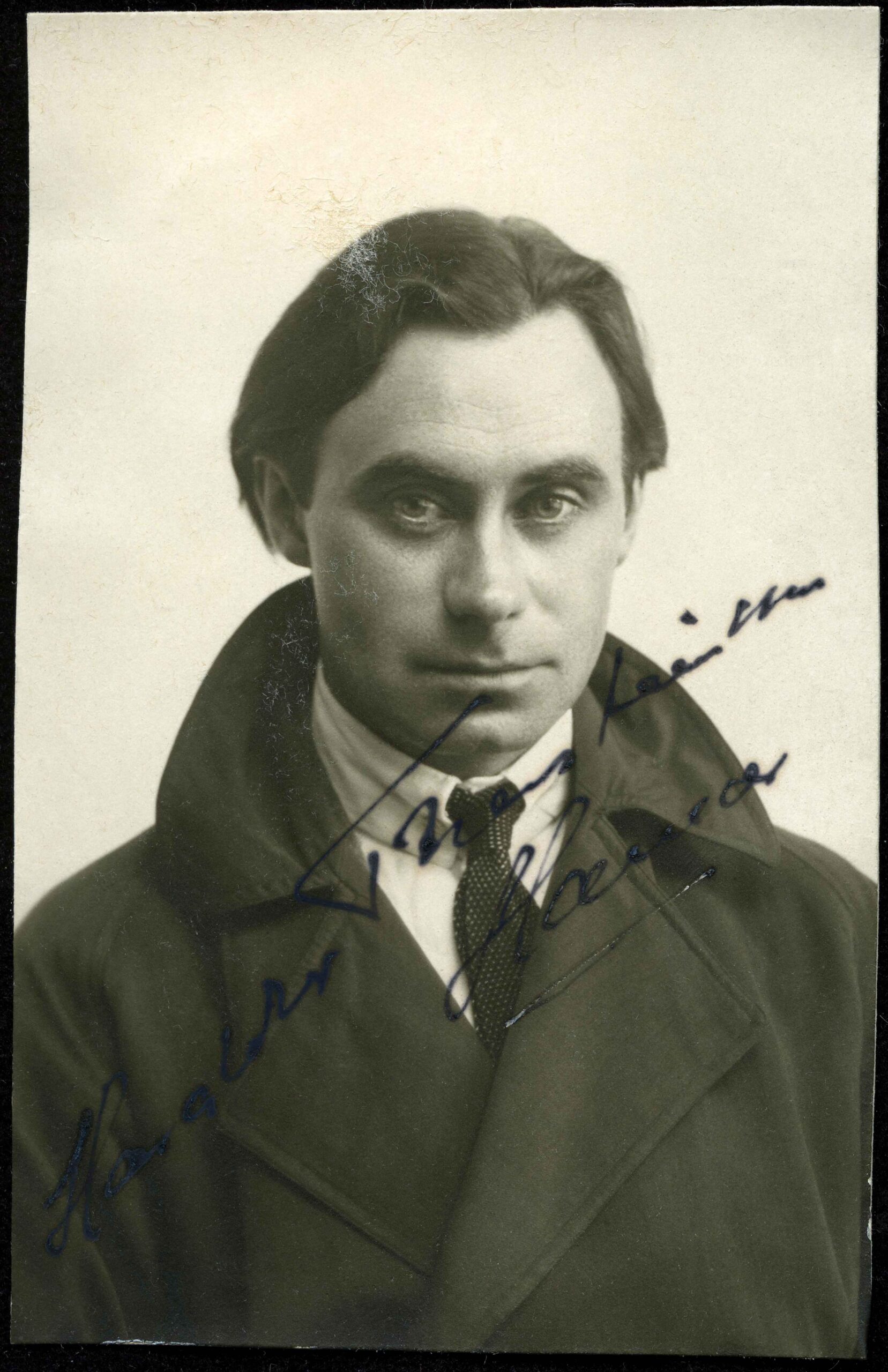

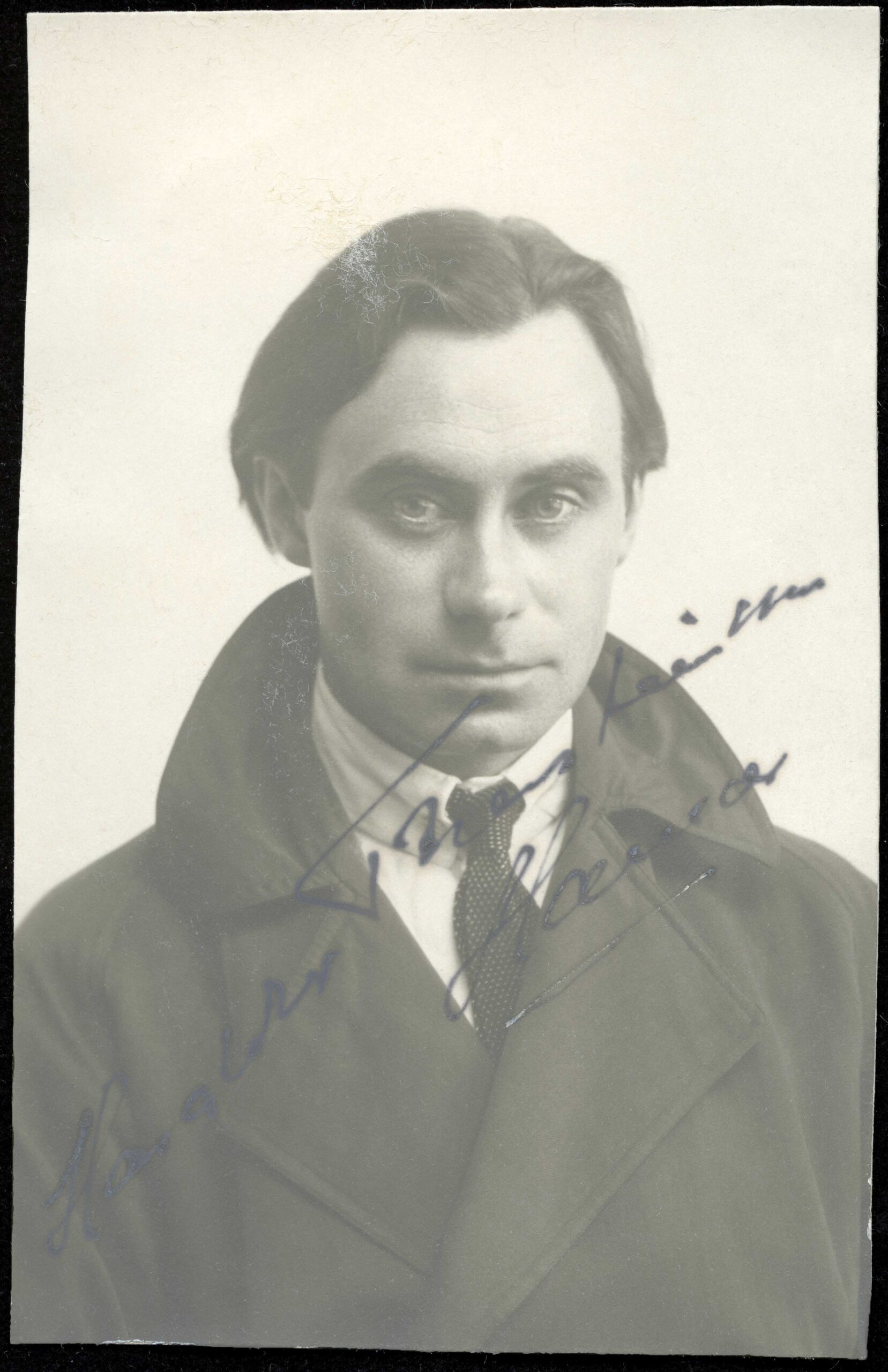

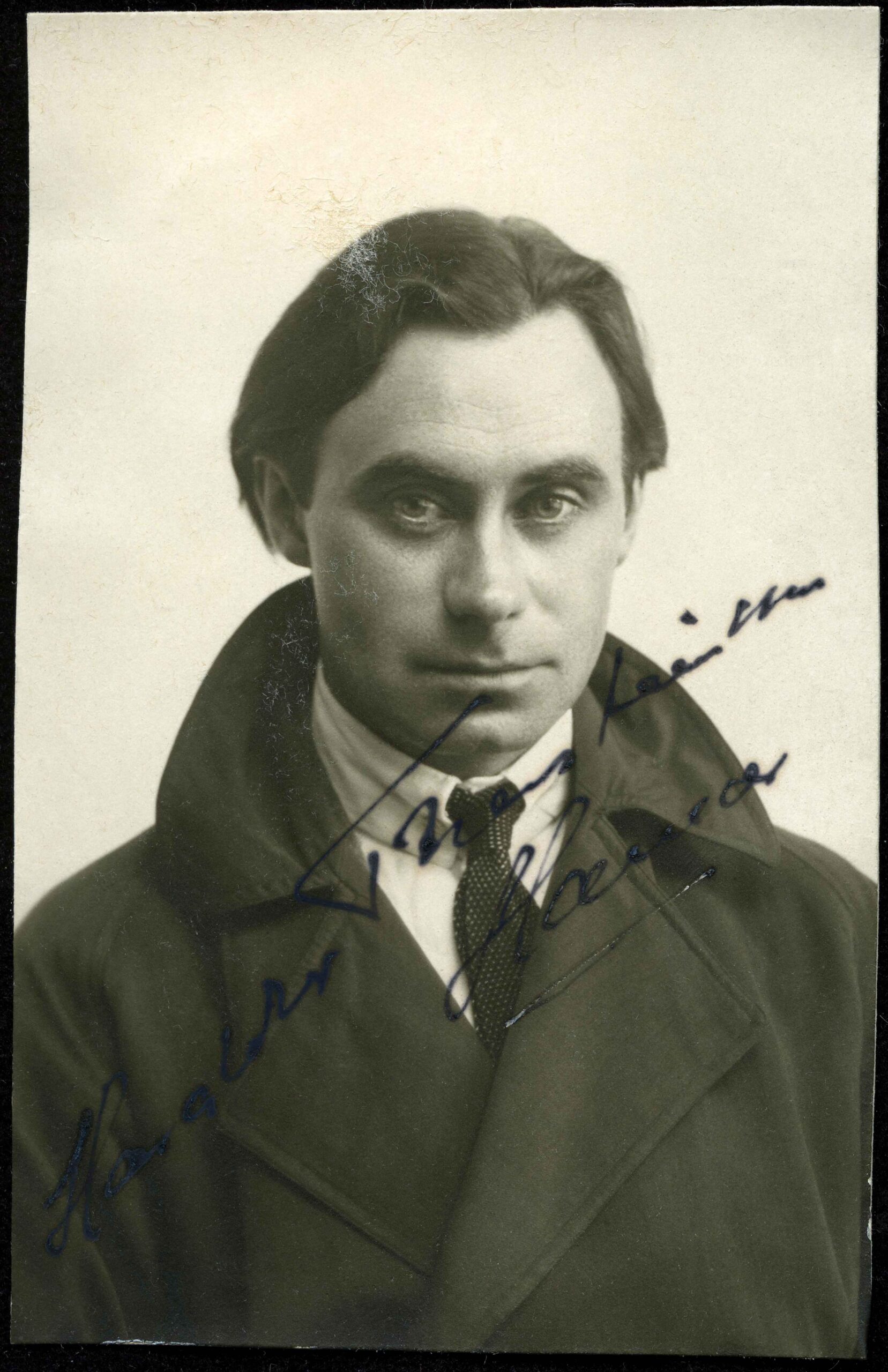

Haraldur’s letters, fragments of which are inserted throughout this text, were written to a friend between 1913 – 1920. They are archived in The National Library of Iceland. (2) The letters have been a constant source of inspiration and even if there are only five of them, they are incredibly rich in emotion and information; a window into Haraldur’s life and mind. Letters and photographs carry within them some of the same elements. They are rich objects that have the ability to hold and distort time, they are carriers of history, of people’s lives. Liz Stanley a professor in sociology compared the two by describing them as ‘flies in amber’. (3) They are reminders of lives lived and time that has passed. There is a photograph of Haraldur in the archives at The National Museum of Iceland, it is a passport photo of him taken in 1923 when he is at the age of 31. It is one of the few photographs that I have found of him and the last photograph taken of him that I have seen. Because of that it affected me differently from other photographs. It is an image where his presence is incredibly strong. His gaze is directed into the lens and in my mind I could see him move about in the photograph, blinking his eyes, following the photographer’s instructions. At this point in his life, Haraldur was there in a photo studio having his picture taken. In the words of Roland Barthes this can be described as being ‘the emanation of the referent’. (4) It refers to the ability of a photograph to hold something more within its flat surface than meets the eye. In this photograph Haraldur’s presence radiates out and affects me here one hundred years later.

“…my soul became a cloud that rained eternal fire, hail and sulphur. But now my soul is getting quiet again, the sky is clear and blue, and if you will accept I will send you few rays as a summer gift to make up for the mess I was in the last letter.”

Calling Haraldur a collaborator is a form of haunting, and trying to make a connection by contacting a ghost through a clairvoyant demonstrates a willingness to be haunted. But I am not the only one who he has haunted. After his passing, his name slowly faded from the family history but he still haunted family members and made his presence known, determined to keep himself from being forgotten. He found his way to a relative that had a meeting with a clairvoyant in the 1970s. He asked the relative to think kindly about him, because it made him feel better in the afterlife. Haraldur also told that relative that he had accompanied his sister during her summer holiday to Italy. Imagine enjoying your vacation in Italy unaware that you are followed by the ghost of your dead brother. Or when another relative met with a clairvoyant and was told that Haraldur was to blame for their partner’s drinking that he was drinking through them. Freeing the living from their mistakes by blaming their faults on those who have passed.

“Sometimes I dream of him, and I have no doubt that it is him that speaks to me. I have no doubt that dead men can influence the living, if they have a certain wit about them, something that I don’t understand to the fullest, but believe me it is for certain. More to come later.”

Not only does Haraldur haunt people in his afterlife he also did it before his passing. The writer and friend of Haraldur, Sacheverell Sitwell wrote in one of his books a chapter titled, Dream of the Icelander, where he writes about a dream where the two of them met.(5) Sitwell had this dream in 1954, three years before Haraldur dies and was certain at the time he dreams that his friend had been dead for many years, because the last time he remembered seeing Haraldur was back in 1923. What he did not know was that Haraldur was still alive in Iceland slowly fading away and in no contact with his former life in England. Sitwell invokes his friend’s ghost himself, without any agency on the part of Haraldur. Making it clear that Haraldur is not the agent, nor is he the performer of the haunting, but the one who is being haunted is the agent and performer. The person that is haunted is the one that conjures him up, dreams of him, speaks to him, listens to him and retells the story.

“Sorry my darling. But I am clearly crazy! I was born in sunshine, I grew up in sunshine, I live in sunshine, and when I die, the sun will set, but only to rise again more beautiful in my eternal world.”

IMAGE

Haraldur Hamar Thorsteinsson, 1923, © National Museum of Iceland, mannamyndasafn nr.Mms-42201, black & white positive print.

REFERENCES

01. Van Alphen, Ernst, Staging the archive – Art and Photography in the Age of New Media. Reaktion Books Ltd, London, 2014.

02. Landsbókasafn Íslands – Háskólabókasafn, handritadeild (Lbs): National and Manuscript Department: Lbs 12 NF: The Collection of Guðmundur Finnbogasson. (Letters translated by Sonja Margrét Ólafsdóttir.)

03. Stanley, Liz, “The Epistolarium: On Theorizing Letters and Correspondence”, Auto/Biography, vol.12, issue 3, p. 201-235. DOI: 10.1191/0967550704ab014oa.

04. Barthes, Roland, Camera Lucida. Random House, London, 2000.

05. Sitwell, Sacheverell, Journey to the Ends of Time – Volume I, Lost in the Dark Wood. Cassell, London 1959.