A Mapping of Recent Years

The summer of 2018 I visited New York and had the chance to look at The Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition Being:New Photography 2018. After some patient cueing and at last with a ticket in my hand, it had a Cindy Sherman Untitled film still on the front of it, I reached the exhibition on the second floor. Large spacious rooms with numerous of photographic work by photographers I had never heard of. After thirty minutes of intensive looking, I came to the end of the first section and there it was; My Birth by Carmen Winant. In a hallway, two walls covered in archival images of women giving birth. A hint to photography’s obsession with death but also an installation of an image we don’t often see. The way Winant uses archival imagery is to be fair smart, the uncovering of a universal image and at the same time a hint to the photo historical spiral of death. One thing noted when engaging with archives is that they tend to directly tell a story about any possible subject and at the same time they indirectly tell something about photographic history, simply because archives are created within a certain frame of time. The archive and its materiality are therefor bound to a historical context. Winant’s My Birth uses the archive in a progressive way in regard to the installation of the work but it also shines a light on remembrance. At the time of the visit these sorts of analysis of photography was nothing I had practiced and therefor my first impression was simpler and in a sense more pure. Stunned by amount, history and archival possibilities.

The photographic medium was born and grew up together with modernity. The endlessly progressive view of the world, both visualised through photography but also noticed within the medium through formats, films and digitalization. No other medium has such a dominant and almost unnoticed present as photography in today’s society and yet is always gazing at the memory of a past. Always creating new images of the world at the same time as it’s archiving it. Photography has its roots and purpose on both sides of the same coin: Progress and Remembrance. This ambivalence is visual in contemporary archival photographic works and it led me to wonder if this might say something about photography’s current state.

Is photography as a medium confronting or getting lost within itself?

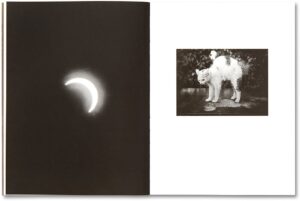

A white cat hogs its back next to a crescent moon and a man sitting on a porch is covered by a white cloud probably as a result of an aged negative or wet plate (FIG 1, FIG 2). In her photographic project Elf Dalia Swedish photographer Maja Daniels dwells into the valley of Älvdalen in Sweden where an ancient form of Vikings Old Norse is still a spoken language today. Daniels has photographed the valley for many years but also during this time found another source to interact with. This source was the archive of diseased local photographer Tenn Lars Persson who lived in the valley between 1878–-1938. The archive, as in Daniels’ case, functions as an ingredient for photographers to work with. Not only for reference but also directly in connection to their own image making. In Daniels’ work it opens up the possibility to create narratives, go back to pin pointed locations and dig into a visual language. When Daniels’ images interact with Tenn Lars Persson’s photographs interesting visual narratives occur as well as a loss of time. Suddenly Älvdalen seems to be a place without a specific time and with narratives spanning over an unclear amount of time. The materiality and interaction in Elf Dalia is displayed as present and past. Often the archival is also the material. Archival images of any kind – whether it is negatives or prints – do usually have some tendency to degrade over time and leave marks as clues of its age. Even if it has no marks of age it is still bound to its materiality as a negative or silver gelatine print. This materiality is interesting because it is also what many photographers seem to work with themselves. Not only by accident but, as Daniels’ work is an example of, also as a urge for the accidental to effect the result. Analogue photography or techniques is as important as ever in contemporary photography. It is an encounter with the past through film types, formats and printing processes. It connects to certain eras of photographic history. Elf Dalia is an interesting example of how Maja Daniels uses the archive of Tenn Lars Persson as a co-author, an image language with the same hunger for mystery and the occult. One way to get there is through the archival and the materiality in photography.

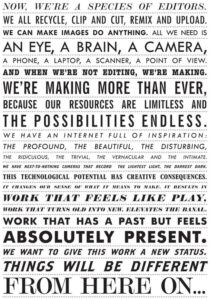

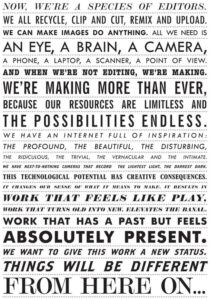

Contemporary photography seem to confront, reflect and being inspired by its past. As obsessive gravediggers it shovels through albums, reveal archives and repeat techniques of the past. At the same time the progressiveness in the usage of the archive is perhaps changing the way we approach the medium. Perhaps best noted in the From Here On Manifesto 2011 by Clément Chéreoux / Joan Fontcuberta / Erik Kessels / Martin Parr / Joachim Schmid. (FIG 3)

The Manifesto from the artists and curators was intended to launch a new age of photography. Encouraging usage of all images in existence. WORK THAT HAS A PAST BUT FEELS ABSOLUTELY PRESENT. This manifesto clearly states the usage of all imagery but also encourage the usage of the massive source we know as Internet. The archive in this sense seems bigger and wider in its meaning. It can mean literally all images ever in existence. At the same time Winant and Daniels turn to quite specific archival sources with a distinct age. Their physical or esthetical age has an importance for the artist’s specific works.

The archive is present but maybe it has always been. The way photographers has dug, used and saved the past of photography. One example is Berenice Abbott, known for her famous modernistic images of New York. Abbott was in the middle of the 30s part of the progressive modern movement of photography and at the same time Abbott was the one whorecognized and saved Eugène Atget’s photographs documenting a disappearing Paris in the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. Atgets images came to have great influence on photographers for a long time. Abbott seemed to have noticed the importance in the past and present of photography. If Abbott would have lived today It would have been interesting to see her view on the manifesto, usage of archives and if she herself would have incorporated images in or with her own image making in a different way.

Atget, Abbott, New York and back to MoMA.

Looking down at my ticket:

7/12/2018 – 4:49PM

General Admission

Student

$14:00

Perhaps the archive simply is some sort of ticket to interaction with another world and time. Just like Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Still on the front of my ticket. It is also an interaction with a visual past, a visual archive. The famous self-portrait series in which we see Sherman reenact stereotypical women characters from 50s and 60s movies. We recognize the black and white 35mm stills but we can’t point out what movie they are from. We simply recognize a universal image created from motion picture, but through Sherman’s work also its normative gaze on women. Our visual remembrance interacts with Sherman’s progressive usage of the non-existent collective archive.

Photography seems like it always has confronted itself in different ways by looking and engaging with what we call archives. Its underlying present also makes it appear a bit lost, its everywhere and nowhere at the same time. The 20thcentury was such a crucial time for what we define as photography today. In the 21th century photography is everywhere all the time. In this sense the medium is lost in its ambivalence with its present and past.

The ambivalence is insecure and self-critical. It is also the potential and power in photography and how we are affected by it. The archive can be a guide within a photographic work, giving the viewer a sense of recognition and an established reality, reassuring us of our past. The artistic interaction with the archive tears this establishment apart and throws us back into uncertainty. It interacts with us on a deeper level where thousands of threads within us recognize, categorize, re-categorize and de-recognize what we just have seen. Our perception of the world is continuously and progressively constructed from photography but with the archival in play, a glimpse of awareness is created. The relation between the viewer and the work is not longer only about what we see but also about how we situate ourselves to the world, time and what we consider being our specific reality.

Bibliography

Museum of Modern Art, Carmen Winant My Birth 2018, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/222741 (Hämtad 2021-03-12)

LensCulture, Book Review Elf Dalia,

https://www.lensculture.com/articles/maja-daniels-elf-dalia

(Hämtad 2021-03-12)

The Guardian, Why You Are The Future of Photography,

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/jul/13/from-here-on-photography-exhibition-arles (Hämtad 2021-03-12)

Wells, Liz, Photography A Critical Introduction, fifth edition, New York: Routledge, 2015

FIG1: Image by Tenn Lars Persson (1878–1938), from “Elf Dalia” by Maja Daniels (2019), Courtesy of Elfdalen Hembygdsforening (EHF)

FIG2: Image by Tenn Lars Persson (1878–1938), from “Elf Dalia” by Maja Daniels (2019), Courtesy of Elfdalen Hembygdsforening (EHF)

FIG3: From Here On Manifesto 2011 by Clément Chéreoux / Joan Fontcuberta / Erik Kessels / Martin Parr / Joachim Schmid.