A walk through the quarry – discovering photography’s sculptural potential

A summer afternoon a few years back I stumbled across a quarry. I was walking down a narrow forest path when the trees suddenly gave way to reveal a barren expanse – a plain of sand and stone banked on one side by a huge cliff of jagged rock.

I had been transported from the familiar landscape of the Swedish spruce forest to what seemed like the surface of Mars. It was a Sunday, and the quarry lay empty as I began exploring it. Here and there lay symmetrically piled mounds of stone, ranging from huge, jagged boulders to the finest sand. These mounds where evidence of what happens in the quarry on weekdays – rock and sand are excavated from the ground, broken up by machines, and sorted into varying sizes for transportation and use in construction. This was a human made landscape. I was drawn to the fact that the ground I was treading on was ‘meant’ to be buried, undisturbed, somewhere deep underground. Instead, because of human intervention, I was now able to access deep time and its geological imprints. Walking through the quarry I had a feeling that the ground held secrets, that the earth turned inside out had something to tell me. Over the coming weeks, which have now turned into years, I returned again and again and quickly felt inspired to make photographic work, to capture the feeling the landscape instilled in me.

Let’s be clear, the quarry I’m talking about here is nothing extraordinary, it’s a perfectly ordinary quarry. The Swedish landscape is dotted with similar places, and if one looks further afield, there are of course bigger and vastly more dramatic mining landscapes to be found. So, however dramatic this place seemed to me, I learned as I started photographing that I couldn’t ‘compete’ with a landscape photographic tradition focused on vistas, relaying the awesome scale and grandeur of place.

In Beauty in Photography Robert Adams emphasises that a photograph can never match the dynamic qualities of being immersed in a place – a photograph will always provide a much-diminished representation. Think of how enveloping and awe-inspiring experiencing a sunset can be. Now think of a photograph of that same sunset – the corniest and most boring of photographic clichés, right? Ostensibly the real-word view and the photograph are of the same scene, however the former has the power to captivate us no matter how many times we’ve experienced it.

Adams states that ‘a serious landscape picture is metaphor’. For the photograph to be ‘successful’ it needs to use its limitations to its advantage, to somehow convey the experience of place rather than trying to convey the place itself. To use place to create a new place. Perhaps the most successful photographs, artistically speaking, are those where the limitations of photography are clearly recognized and used consciously to create something more, something that through a combination of composition, form and light speaks beyond the referent subjects of the image. The problem is that photographs are often treated as slices of reality and not as art objects in parity with painting or sculpture.

We tend to talk about what’s ‘in’ the photograph – as in: what is it? where is it? when is it? who is it? – what the photographer Wolfgang Tillmans has deemed the ‘w-questions’ in photography. Questions that photography seems to unescapably evoke in the viewer. But as well as ask the w-questions, which all treat photography as a transparent window showing us the things themselves, we should also ask what does the image, separated from its ‘real’ subject propose to us? Is it possible to view a photograph and not think about the w-questions? And can the photographer steer the viewer away from posing these questions?

For me, it’s photography’s duality that excites me – how we’re able to shift our gaze back and forth, between contemplating the photograph as ‘pure image’, de-coupled from the world, and as representation that is, inexorably, linked to the world.

Through my frequent visits to the quarry my photographic interests slowly shifted. I became numbed to the grand and beautiful vistas that wouldn’t let themselves be photographed and instead began to move closer, focusing my attention to the details in the landscape. The place itself became of less interest and I began seeing the quarry more as a canvas, a place where I could, to some degree, create the possibilities for images to arise by being attentive to my surroundings.

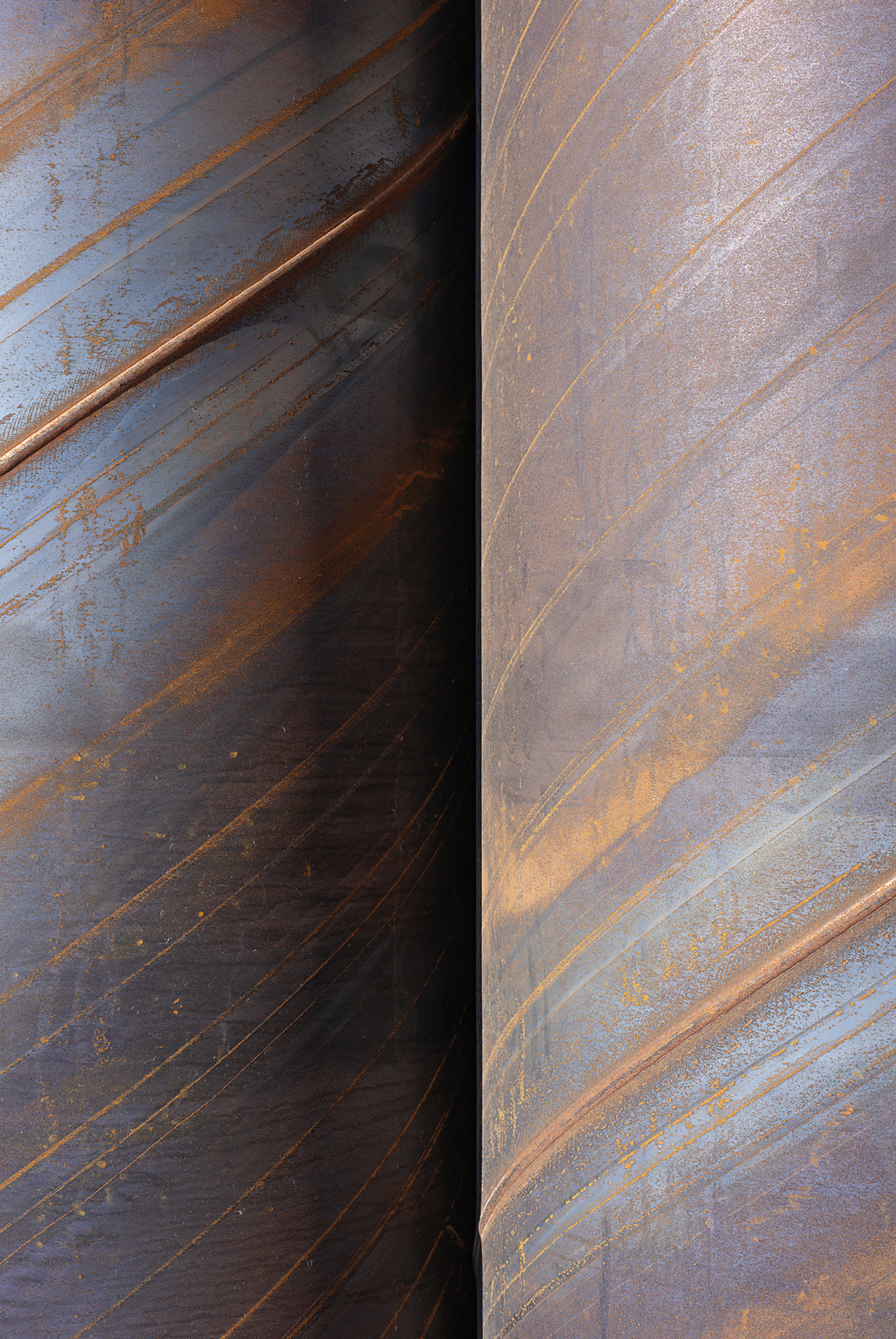

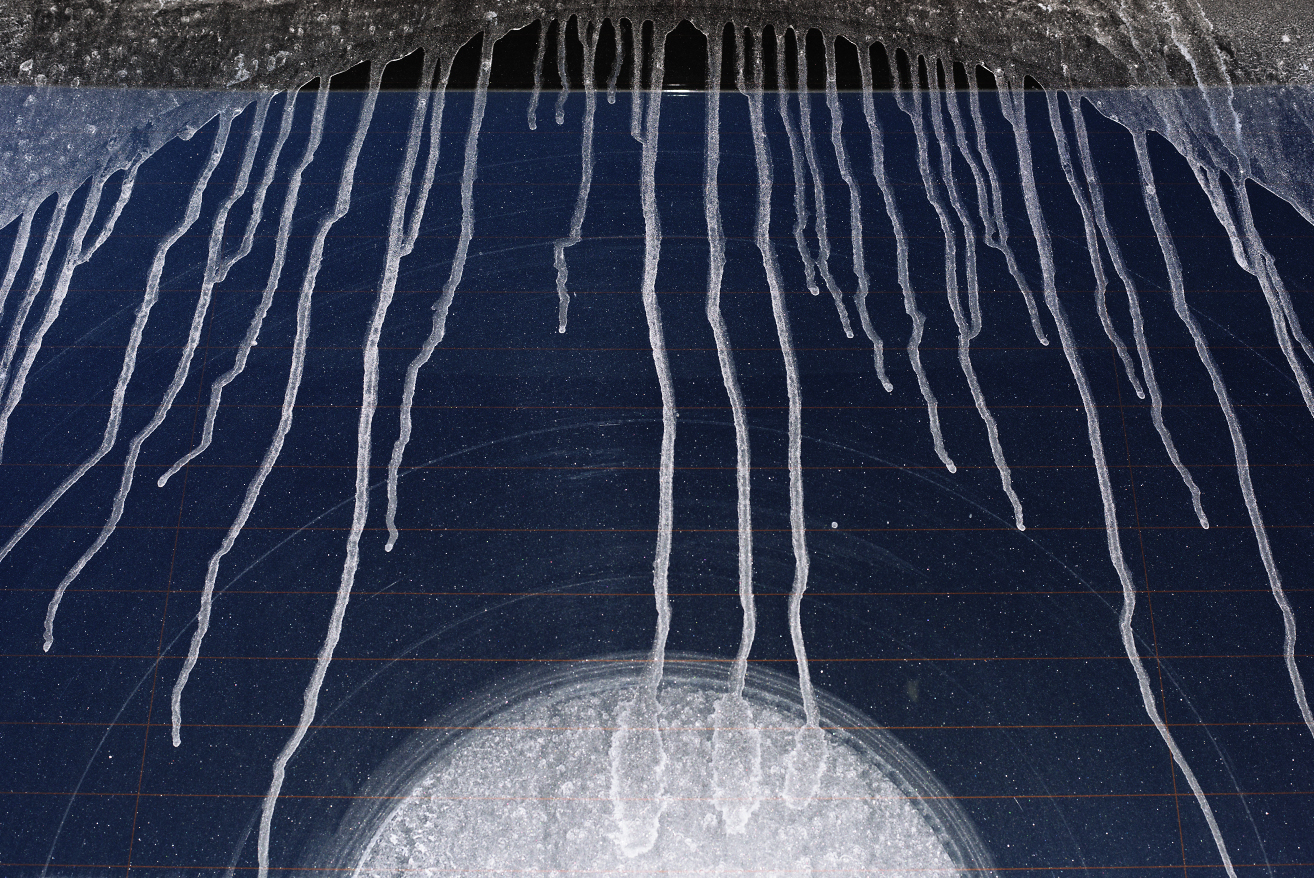

In Maquette, a series of black and white images showing a downpour of wet sand down a steep embankment, the quarry one day offered me ready-made sculptures. I view these photographs as records of records, a kind of meta photography of images that have already been stamped into the earth. According to the Oxford English dictionary, Maquette is defined as ‘a sculptor’s small preliminary model or sketch’. I chose this playful title to emphasise a sculptural reading of the photographs – the landscape through the forces of nature is creating imprints of itself. Sculptural models through which my photographs then become fully fledged ‘sculptures’. Imprints of imprints, images of images.

My photographic work isn’t about creating physical sculptures but finding them and enhancing them through photography. It’s about finding the right vantage point, through which an image can be made that abstracts the subject matter away from the recognisable. It’s about destabilising the vantage points that are commonly offered – in the case of landscape photography: vistas, horizons, people, trees, and other markers from which we can deduce scale and more accurately place and assess the image. Instead, I tend to move closer, to fill the entire frame with the ground to destabilise notions of scale and recognition.

I want to argue that the intervention that is photography, the purposeful act of making an image has the possibilities to bestow sculptural qualities onto subjects that we normally wouldn’t recognize as such. Here, it’s the photographer and the camera, working in tandem, who are the sculptors. Through photography, with its limited frame and fixed perspective it’s possible to concentrate form, to separate it from its original context. The world around us lacks boundaries or instructions from where or how to view it, herein lies photography’s sculptural potential.

Photographs are their own place. They draw on the world, on place, to create new places. Places that are also, to an extent, out of the control of the photographer. We point our cameras and hope that it makes an image for us that can transcend the visual through the visual, to give us something beyond that which we photographed.

References

Adams, Robert. Beauty in Photography. New York: Aperture, 2009.

Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.lexico.com/definition/maquette (retrieved 2021-12-22)