Carefully Held Hands

Elin

The water is cold but the hands are burning. The red fingers are starting to shrivel, clenching a wet piece of cloth. A pressure pulsates under the nails. Beneath the water the hands look bigger, swelling as if they’re about to dissolve. They’re always swollen these days even above the surface. She stands there for a while observing them, pushing them down towards the base of the bucket, harder and harder, and slowly the water settles and places itself like a protecting cover of glass.

There’s been many weeks since she was allowed in the washing room. They don’t like to keep her there since she scrubs the fabrics until they break. Always the same fabric, that coarse striped fabric made by the sick. Some of them have been used for so long that they’ve become worn and frail, almost transparent. On those pieces the stains never go away, no matter how long or hard you scrub. Fat, food and bodily fluids break up the lines, creating islands of color, darker and more clear than the worn out gray of the fabric.

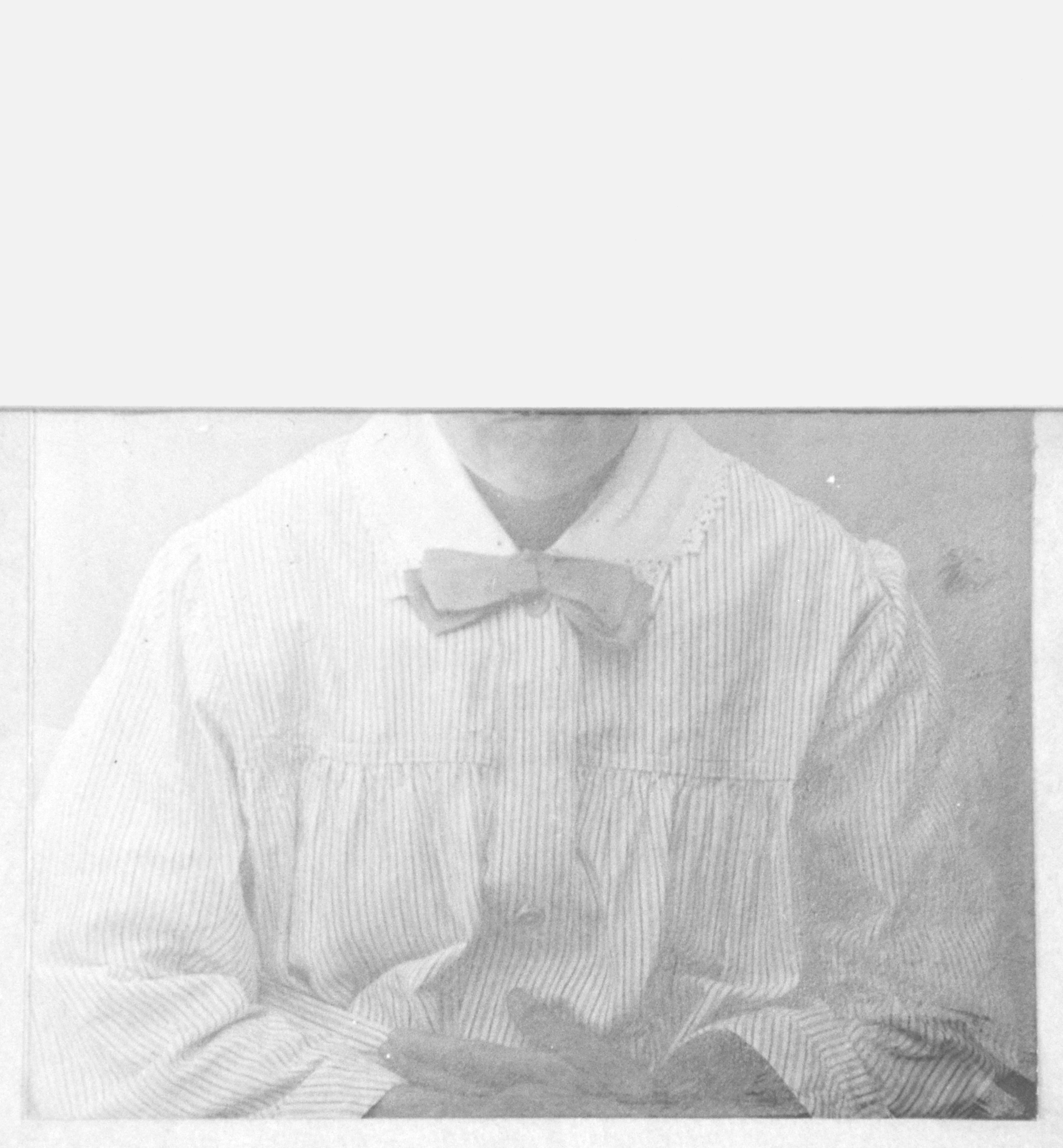

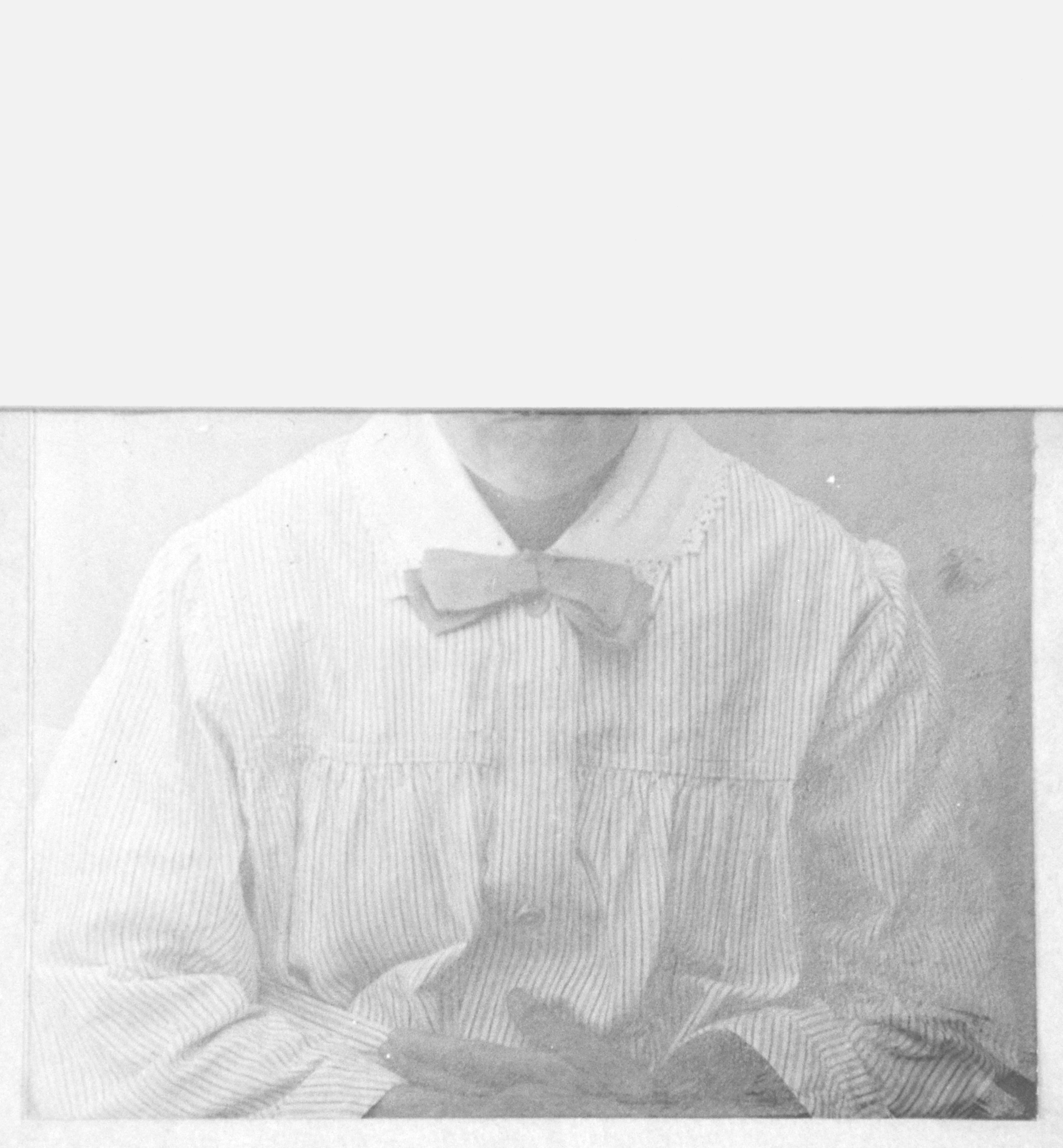

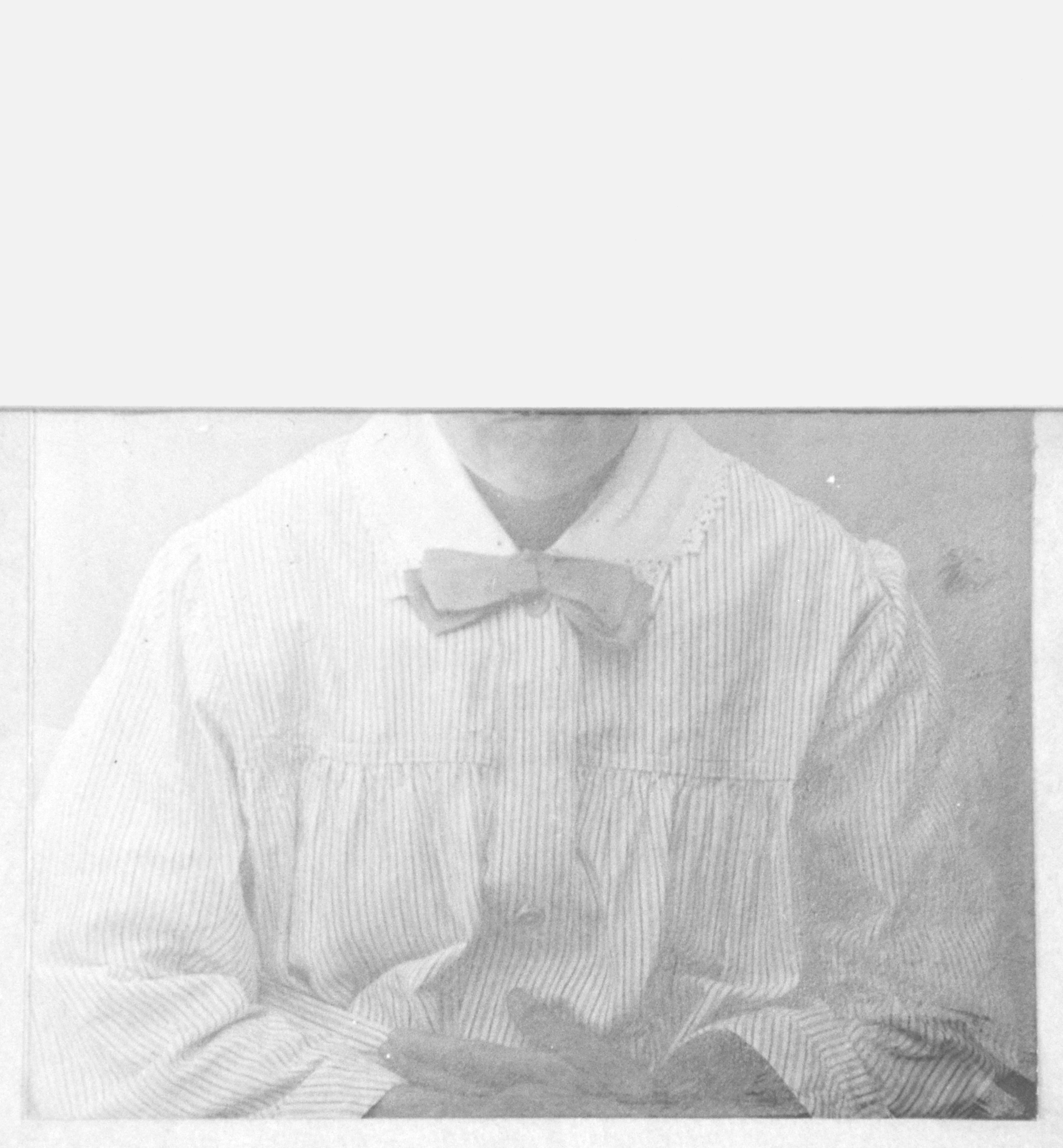

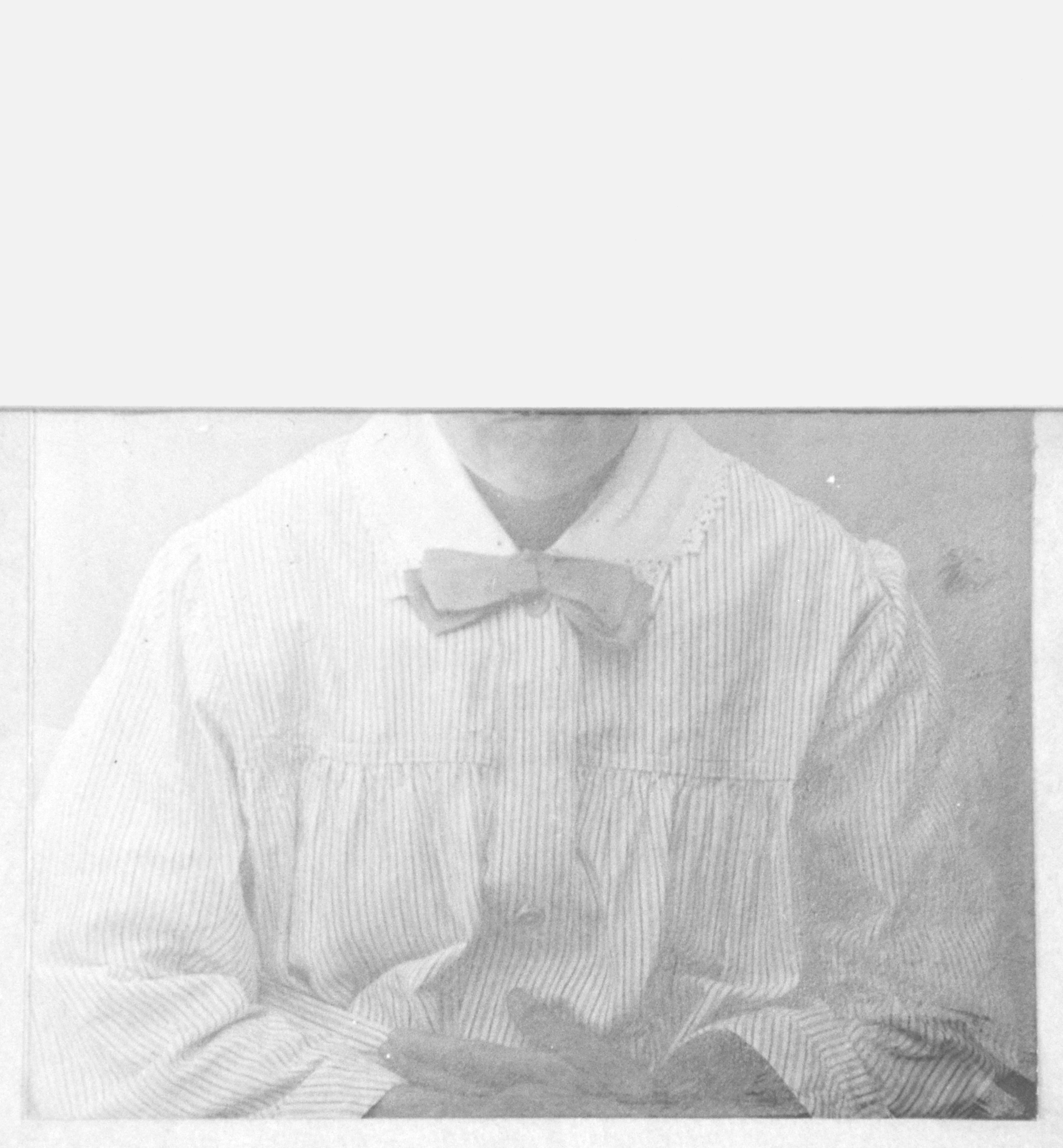

I’m looking at an old black and white photograph. A woman is sitting there in a striped dress with a neat collar, her hands folded in her lap. We can only see her chin and lower lip since the photograph has been covered by a piece of paper. I first encountered this image at the regional archive of Västerbotten, while reading patient journals from female patients at Umedalens mental hospital during the 1940s. This was the first file I found that had “lobotomised” neatly handwritten on the cover. The photograph was not yet covered and the woman’s face looked back at me with an expression of combined defeat and defiance. The details of her face are lost to me now but I remember how it drew me in, the complexity of her expression and the hands in her lap. She held them so carefully, one hand open towards herself and the other held to support it. There’s such gentleness in the positioning of the fingers, as if they’ve lost their function of grasping.

Her name was Elin and the picture was likely taken at Furunäset hospital where she was first placed before being sent on to Umedalen. She was at this point well acquainted with public care institutions, having been under its wings at different times of her life. She ended up at Furunäset after being violent with her husband and children then running away from her home. In the journal the doctor described her as “more lively than dim”, that she was something of a brooder with an “unyielding disposition” and that “she’s often sad and anxious”, “she does not know where her children are and does not long for them”.

Two figures are moving along a gravel road, it’s getting dark and the forest is rising like two walls on each side. They are walking slowly because one of them is small. She’s holding her mother by the hand and with the other she is keeping a sturdy grip on the knot beneath her chin so that the scarf won’t blow off of her head. Snot is running from her nose down towards her mouth, the taste of salt and earth. They’ve been walking for a long time, but the weariness has passed and the legs are moving mechanically now. Onwards, endless roads and forests. Sometimes they see a flicker of light through the trees and smoke slithering upwards, when that happens the mother’s face stiffens and she increases her steps, the girl can feel her pulse through her hand.

One cannot trust people, she has learned that, cause if you do they will take them away from each other. They give you food and shelter but as soon as you turn your back they’ll have summoned the authorities. Many times they have run until their feet were red with blood, away from the houses, towards the forest and the darkness.

Now the mother’s walking there calmly, with her gaze directed forward towards the point where the road makes itself visible from the darkness. In a moment she will stop, listen for a while and then deviate from the road. The girl doesn’t like sleeping out here among all the unseen creatures, among the cracking and howling, she imagines all sorts of horrors behind the trees, unseen devils just waiting to put their claws in her and drag her down their dark pits.

Mother and daughter huddle together beneath a large fir, whose heavy branches bend down and protect them from the wind. They sit closely and the mother takes the girls hands in hers, exhales on them and rubs them warm. Her own hands are dry and covered in small wounds, cuts like rough pine needles along the surface of the skin. Five years ago she left the husband and the home, then the girl was eight months old and wrapped in a bundle. They haven’t stopped since then, nor have they arrived, just walking away, onwards. The girl knows better than to ask.

“The patient’s parents are workers. They were not together for more than eight months after the marriage took place, since the mother abandoned the husband and took the girl, walking until she was five or six years old. The mother only wanted to wander the roads, was never at peace and lacked any sense of living in an orderly fashion.”, the doctor wrote in his notes.

Elin was lobotomised after many years at Umedalen. She was apparently violent after the operation, hitting her hands together and often turning them on herself. “Her hands are almost always swollen” it says in the journal. She lost some of her balance and kept falling over. She was shouting and quarreling at night. “At times something comes over her, she cannot say what, that puts her in anger”.

She died at 08.25 a.m. on the 12th of december 1947, at the age of 52. “Schizophrenia + Haemorrhagia ventriculi lat. dx. post lobotomiam.” Death due to lobotomy. The journal doesn’t mention where she was buried.

The reddish pink houses stand in slightly stretched rows up on a hill with geometrically planted pine trees all around. There is something odd with these pines, as if their placement is meant to give an impression of harmony and well-adjustment. No wild sprouts or bushes anywhere, just well kept grass and these trees. Everywhere they stand, upright and exposed with their bare trunks.

When she’s laying in her bed she can see the top of a tree and with some luck she might see a bird, but they usually stay away from this place, there’s nothing for them here. Even the tree’s branches are trying to get away, climbing as far up as they can to avoid the people underneath. Too high for anyone to reach. Only here are they on the same level, when she’s floating in her bed on the second floor.

She has to tilt her head backwards completely to see it and rest it on one of the top vertebrae of her spine and can only hold still for a short while. It’s easier from the day room where she can sometimes sit in a chair by the window.

The nights are the worst, she can only see darkness then. Anger sets in, takes control of her body which hits and tears at everything and at itself. Hands press against her skin, nails that scratch and pull, tearing her flesh. She hits her hands together with such force that they swell up and she can no longer feel them. The walls are pressing in, closer and closer and the anger is trying everything to keep them away. Holes and piles of gravel are what remains. Then injection and a belted body, hindered movement that twitches and pulls.

Umedalens hospital on the outskirts of Umeå was at its prime one of the largest mental institutions in Sweden. It was also the institution that performed the most lobotomies on patients in this country and the majority were women. This procedure cut connections between the prefrontal cortex from the rest of the brain, thus cutting away those parts involved in speech formation, working memory, mental imagery, gaze and risk processing. The part of the brain where a lot of one’s personality is located. The death rate was high and many patients died as a result of hemorrhage and other complications. Of the forty two women I found between the years 1947 and 1951, with “lobotomised” written on the cover of their journals, twenty three died as a direct result of the procedure. Elin was one of them.

Most of these women were diagnosed with schizophrenia, a diagnosis more loosely used in those days. The psychosurgery of lobotomy was considered as a last resort for those patients who were especially difficult and it was regarded as the revolutionary new step in mental care, awarded with the Nobel prize in 1949. But it was quickly criticized and by the 1950’s it was slowly being outdated by the introduction of psychotropic drugs. Like Elin, the majority of the women came from a poor background. Some of them had a long history of mental illness, others seem to have suffered from a sudden psychosis or postpartum depression, conditions that spiraled out of control and even more so within the restricted walls of the institution.

The archival staff chose to cover Elin’s face before sending me the photograph. Seventy five years after her death I found this to be a further act of violence towards her. As if the shame was still placed on her shoulders even after so many years. As time passed my view shifted and the covering became more an act of care than of shame. As Temi Odumosu puts it in her article on The Crying Child, problematizing the role of museums and other institutions in digitally distributing photographs of violence and oppression:

“What if the digital object could do all the speaking that the original could not do? What if the digital object could say on behalf of persons represented: ‘Look, here is my story. I’ve experienced pain, and now you are part of it; tell me what you intend to do with me?’ And such a question, extended by way of a collection to the invisible user, seems fair.”

The archive chose not to give everything to the onlooker, to restrict access to this face and thus forcing us to listen instead of simply looking. Elin is protected from our gaze, she’s no longer just marked as “the mad woman”, she’s more complex than being restricted to the photographic imprint on paper or pixels on a screen. Her voice carries through time in all its rage and frustration.

References: Ögren, Kenneth. Psychosurgery in Sweden 1944-1958: The Practice, the Professional and the Media Discourse. Department of Clinical Sciences, Division of Psychiatry and The Department of Culture and Media. Umeå University, Umeå Sweden. 2007

Odumosu, Temi. The Crying Child: On Colonial Archives, Digitization, and Ethics of Care in the Cultural Commons. Current Anthropology, Volume 61, number S22. The University of Chicago Press. 2020.