Copying the right to use

Behind the curtain you have a photograph of the iconic bronze statue of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale The Little Mermaid, one of Copenhagen and Denmark’s most visited tourist attraction. The reason why this national symbol is seen behind a curtain, is perhaps not really because the statue is not worth of showing, but actually because I don’t have the permission to show an image of the statue in this article – at least without applying and paying for the rights first. The reason for this is simple, the copyright for using images of the renown sculpture is strictly upheld by the family of the artist, who designed and constructed the statue of the famous H. C. Andersen fairy tale from 1837.

However, this article is not really about The Little Mermaid. Moreover, it is an investigation into the capability of how to be able to show a photograph of The Little Mermaid without actually showing an image or a dominant representation of The Little Mermaid – in order to avoid interfering with the protected copyright rules. It maybe sounds like hocus pocus or gibberish talk; however, it is important how the definition is described, especially when navigating within the law and legal regulations. I will get back to this later.

The story behind the making of the statue and the heirs of the artist.

In 1909 the brewer, businessman, art collector and philanthropist Carl Jacobsen, the son of the founder of Carlsberg, commissioned the sculptor and artist Edvard Eriksen to create a statue in homage to the fairy tale of H. C. Andersen The Little Mermaid. The story goes that Eriksen, who was one of the most prominent sculptors in Denmark at that time, used his wife Eline Eriksen as model for the mermaid’s body and the head, Ellen Price, a Copenhagen Royal ballerina, who Jacobsen have been fascinated by when he saw Price in the role of the little mermaid in 1909. Four years later, in 1913 the statue was finished.

Since his death in 1959, the heirs of Edvard Eriksen got the reputation of strictly enforcing the legal copyright protection, which every artwork is protected by. It is perhaps the most well-known copyright case in Denmark, when it comes to reusing, to document or to illustrate the statue for use in a public or in commercial context. Throughout the years the statue has been an expensive encounter and an ongoing headache in the Danish tourist and news media world. Examples of this will be presented a bit later, first it is important to know the legal definition of using copyrighted material.

Across time, space and perspectives.

Throughout my own experience in my practise as an artist, most of my work is surrounding the question of using copyrighted materials. In my work I explore elements of found or archived imagery, which is a result of journeys related to my personal life and story. Whenever the pictures are found physically in the urban landscape, in connection with a local investigation, invited to work in local archives or the use of digital archives the images enable me to work across time, space and perspectives. In my works I often create a cohesive image or installation, often resulting in recognizable shapes and figures – every created by a selective index of images.

My method makes me able to lift up topics of national identity and memory, human rights, consequences of freedom of press, the importance of the archive and its fragility. All raising questions and dilemmas that perhaps will not be possible without the help of the person or people who took the photographs. It is these experiences I have gained through many years of dealing with copyright content, that have given me the foundation to write this article.

Each image must be treated individually, which is also why I often use the raw images I find in my artworks. For me the photographs represent an objectivity, a value and symbol of a human trace, which was captured in a decisive moment via the viewfinder of the camera. One could say an artifact, where the value is depended on the eyes of those who see it and the message it gives.

The legal definition of copyright.

The basic law of all copyright cases is, that each case must be treated individually. In connection with Danish law there are a lot of legal regulations, 93 individuals plus all the sub-points and additional paragraphs[i]. However, in the interest of this article the main captions are following:

§1. Anyone who produces a literary or artistic work has the copyright to the work, whether this appears as a fiction or non-fiction production expressed in writing or speech, as a musical work or stage work, as a film work or photographic work, as a work of visual art, architecture or applied art, or as it has been expressed in other ways.

§2. The copyright, with the limitations specified in this legislation, entails the exclusive right to dispose of the work by producing copies of it and by making it available to the public in original or altered form, in translation, reworking in another literary or artistic form or in another technique.

§63. The copyright to a work lasts until 70 years have elapsed after the author’s year of death.

The 70 years mentioned in § 63 is worth noticing in connection with the statue of The Little Mermaid. To be precise, on January 1st 2030 all copyright related to the sculpture will be expired and erased.

To be legal or not to be legal, that is the question.

Just before you try googling pictures of The Little Mermaid and conclude that there are several examples of photographs of the statue, you need to be aware of one more §. Reportage of day events:

§25. When a presentation or display of a work is included in a day event and it is reproduced in film, radio or television, the work must be included in the extent that it happens as a natural link in the reproduction of the day event.

This means with exceptions of course, that most of the photographs you see are in one way or another linked to an event connected to The Little Mermaid. In most cases the examples you see on google have been in connection with vandalism of the national symbol.

However there have been several examples where the heirs of Edvard Eriksen have been disagreeing with the importance of showing the statue in a current situation, or felt violated in the use of The Little Mermaid in a processed version.

For instance, back in July 2001, where the Danish union newspaper Folkeskolen a magazine for teachers working at elementary schools, was convicted to pay 16.250 DKK for royalty, violation and lack of permission to the statue in a drawing. The cartoon on the front cover of the magazine illustrated the Mermaid looking amazed at a Swedish flag. The newspaper used 80.000 DKK in expenses for legal assistance.

Recent example of an expensive encounter with the family, was a case about an article published in the Danish Newspaper Berlingske in 2020. In a cartoon the statue was depicted as a zombie with red eyes, caring the danish flag, while the phrase “the evil in Denmark”, was written on her stone. The infringing plaintiff won the court and the Berlingske’s editor-in-chief, had to pay 285.000 DKK and the costs of the case 34.200 DKK. The case was later appealed[ii].

Common for both cases was that the statue was a main motive of the illustrations, which bring us to the next step in my investigation.

The collage rule.

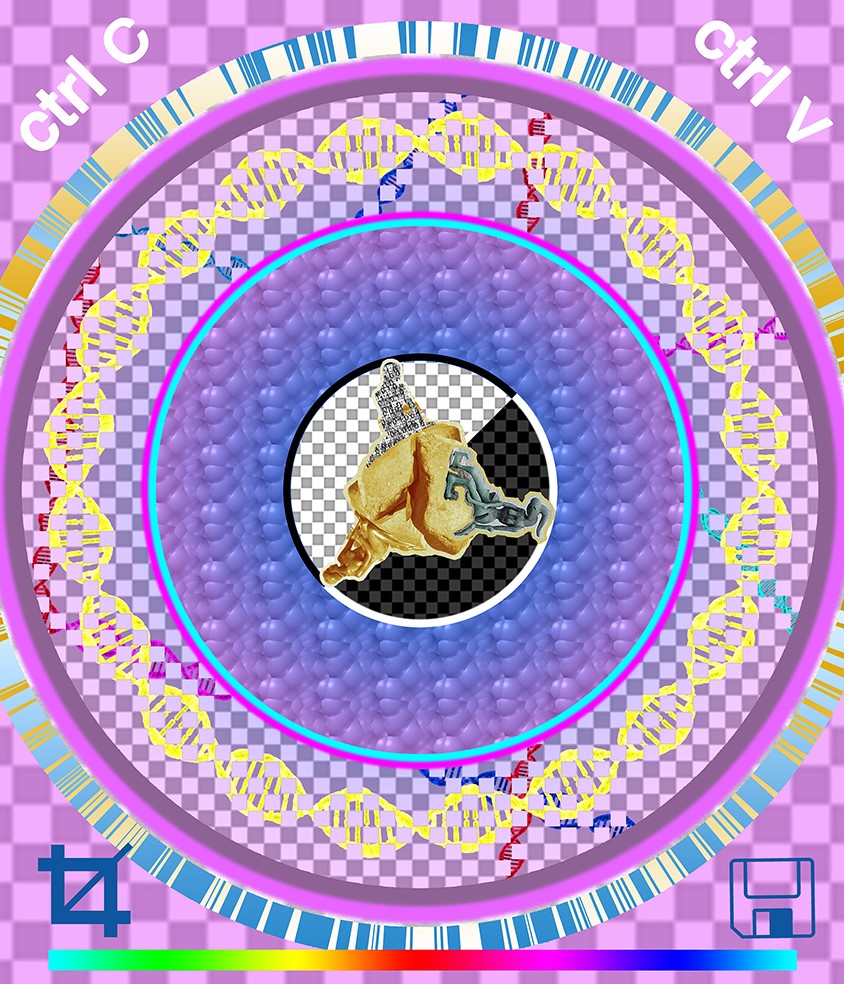

In 2008 the Danish visual artist Bjørn Nørgaard won a case against the heirs and also the right to use the statue in one of his collages without violating the copyright rules.

Bjørn Nørgaard’s work, a colourful gobelin, was made in connection to the 200 years jubilee of the birth of Hans Christian Andersen in 2005. Nørgaard had placed two identical photographic representations of the statue in a dialogue with two other identical photographic representations of his own genetically modified version and statue of the mermaid. All four images were placed in the centre of the collage surrounded by circles, human looking forms, shapes and symbols.

The basis of the court’s decision was that Bjørn Nørgaard’s collage constitutes a new and independent work (§4.2), and that the use of the photographs was not suitable to enrich Bjørn Nørgaard or the publisher on the expense of their partnership. In the decision it was made clear that the original Mermaid did not have a dominant location in the artwork. Nor did the court see any violation against the representation of the original Mermaid.

The basics of the experiment.

In the decision the court was focusing on modifications §4.2.

§4. The processing of an original work of art: The person who translates, reworks or otherwise processes a work, including transferring it to another literature or art type, has copyright in this figure, but cannot have it in a way that is contrary to copyright of the original work.

§4.2. The copyright of a new and independent work, which is generated through the free use of another, is not dependent on the copyright of the original work.

And also the question of the role of the motif in §24:

§24. Reproduction of works of art, etc.

Works of art that are part of a collection, or that are exhibited or offered for sale, may be reproduced in catalogues of the collection. Such works of art may also be reproduced in notices of exhibition or sale, including in the form of transmission to the public.

§24.2. Works of art may be depicted when they are permanently placed on or near a place or road accessible to the public. The first provision does not apply if the work of art is the main motif and the reproduction is used commercially.

As a first thing to my experiment, I want to make use of another paragraph which I have not addressed:

§70. Manufacturers of photographic images.

Whoever produces a photographic image (the photographer) has the exclusive right to dispose the image by producing copies of it and by making it available to the public.

§70.2. The right to a photographic image lasts until 50 years have elapsed after the end of the year in which the image was produced.

This paragraph also makes me able to use the original image of the Royal ballerina dancer Ellen Price in the beginning of this article, which was taken in 1909 and therefore 112 years ago – meaning 62 years after the expiring copyright.

For this experiment I want to use the photographer Sven Türck image of The Little Mermaid as how it looked in 1954 – 68 years ago. Nevertheless, the statue is still copyrighted in the form it has in the photograph. As a solution for this I want to use the gained experiences that Bjørn Nørgaard had in the legal encounter with the hires. The Mermaid should represent or question different story than what the statue portrays, it should not be the main motif in a collage, and I should not modify the original representation of the statue in a way that can violate the hires – one of the strongest arguments in many of the cases raised by the family. Moreover, and in relation to the decision in Nørgaard case, I need to add some circles, human looking forms, shapes and symbols. And finally, I need to add something that makes a dialogue with the mermaid without talking about the statue.

The Result.

One thing should perhaps be addressed in this connection. At this point we are not able to conclude if the experiment turned out to be a success or not – at least not before the rule of the 70 years is applied 9 years from now, January 1st2030. It is of course my strong belief that I have the law on my side since, this article is seen as a literary academic artwork in conversation with my art practise, to research and question the legislations in connection with copyright material. Here The Little Mermaid copyright is just used as an example, which in theory comply to all literary or artistic works. § 1.

Nevertheless, only the future will tell.

References:

https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2014/1144

https://www.folkeskolen.dk/13124/folkeskolen-tabte-til-havfruen

H.C. Andersen Evigheds-KunstKalender

https://journalisten.dk/havfruens-arvinger-tjener-fedt-pa-ophavsret/

Transcript of judgment B256101Y – JJ, 2008, Østre Landsret

Footnotes:

[i] The paragraphs mentioned in this article are translated by the author. Reservations are made for any wording that has not been accurately translated.

[ii] The result of the court is by 04.04.2021 still ongoing.