Darkroom: Where time sculptures silence

Remaining: 7 673 days, 14 hours and 12 seconds.

Place: The darkroom. With the smell of chemicals and the inherent limitations of red light, the darkroom is a place that illuminates the phenomena of time. Here, day-to-day time ceases to exist and is replaced by a different rhythm. Perhaps it’s here that it becomes most evident, the transition – not a transition forward or backward, but through. From what I thought I knew, to what I don’t yet understand. Here, time has rather become a passage I live in and with, finite and unpredictable. Time that cannot be tamed, only inhabited. When I develop an image, I cannot force the result faster than chemistry allows. Time is my partner and sometimes my opponent. I wait while the image emerges, layer by layer, as if the subject has been lying dormant, just waiting to become visible. The film director Andrei Tarkovsky talked about ”sculpting in time” (1) , and in the darkroom I realise that I can only guide the process, not dominate it. Time determines when the picture is finished. In that moment, I experience a vertical movement, a deepening both in the image and in myself. It’s as if, in that moment, I’m standing still and moving forwards.

I recognise symbols and their meaning which often appear in my images. At first, they appear as fixed shapes, but over time I see how their significance shifts. They do not change because I consciously alter them, but because I return to them with a different gaze. The philosopher Julia Kristeva talks about ”monumental time” (2) – a cyclical movement where we return to the same point but see it from a new angle. Each return, I notice, is not a repetition that leaves everything unchanged, but a transition where I carry previous experiences into the next encounter. When I look at the symbols in the picture, they take on a new context, a new charge, depending on where I am.

The transition involves me digitally manipulating the light and contrast of the image on the computer. This is a first transformation, where I add something of myself through technology. A further movement occurs when I print the image and re-photograph it with my analogue camera and then bring the negative into the darkroom. I overexpose some areas, leave others hidden, experiment with different chemicals. A different shadow appears, a different rhythm in the image. The image bears traces of several temporalities – the original exposure, the digital adjustments and the analogue post-processing. The layers of time ‘speak’ to each other, and I see how they correspond across different phases of my own artistic process.

Will those who view my images experience the same time layers as I do? Or do viewers create their own time space in the encounter with the work? The author bell hooks describes how time can be a place of freedom, and that resistance is sometimes found in the ability to stop and look slowly (3). Perhaps this is what happens when someone looks at a photograph for more than a brief second: the image gradually opens up, new details appear, and a transition takes place in the viewer’s mind. Every image has the potential to become a mirror in which the viewer sees something new – not necessarily what I saw. Seeing is not a passive act.

I read into the philosopher Hélène Cixou’s text “The Laugh of the Medusa” that at the same moment we try to approach something, it also changes in us (4). My images bear the stamp of my temporality, but in the encounter with someone else they are part of their time. At the intersection of the artist’s time and the viewer’s time, a space is created in which the image continues to change. My experience of transition is not about leaving something behind, but about reshaping it and carrying it forward into a different context. When I look at my photographs in retrospect – sometimes long after they first became an image – what I see is not a linear journey from start to finish, but a constant cycle of questions, shapes, light and shadows. I’m reminded of Kristeva’s (5) description of monumental time: we’re not just moving forward, but returning, reshaping, unfolding. There, in the cyclical movement, I become aware that time isn’t something that is consumed, but something that is ever present.

I once thought that time would give me ready-made answers, but instead it has taught me to ask more questions. The transition isn’t about a straight line from ”then” to ”now”, but about how each step can open new layers of understanding. This is how I see my artistic practice: letting the images develop in their own rhythm, and for myself to live in that rhythm. Just as I once clung to numbers in the hope of clarity, I now try to let them slip through my fingers instead. In the darkroom, when I let my eyes rest on, and return to the same photograph, more layers of interpretations emerge from the symbols in the image. I experience a transition that never ends. Is this the moment when art and time come together? Time has become my co-creator. Every time I allow time to enter, something new emerges. In this sense, the photograph creates an ongoing dialogue with time itself.

I have moved away from the idea of the precise rhythm of efficiency, where hours and minutes are stacked in neat columns, to an artistic practice. Where slowness is not a denial of action, but a way of letting the language of time speak. The passage of time shapes the work at least as much as I do, and instead of dictating the final form of the work, I follow the layering movement of time. Like a curator of this transition, a custodian of an image that is never still. Each time I return to the same image, it’s never the same, and neither am I.

Remaining: 7 139 days, 9 hours and 51 seconds of a linear statistical life.

Place: In transition – What impact does this have on the remaining days?

Notes

- Tarkovsky, Andrei, ”Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema.” Translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989), 63.

- Kristeva, Julia. ”Women’s Time,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 7, no. 1 (1981): 16-17,

- Hooks, bell. ”Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom.” New York: Routledge, 1994, 13–14.

- Cixous, Hélène ”The Laugh of the Medusa.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 1, no. 4 (1976): 875-893.

- Kristeva, Julia. ”Women’s Time,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 7, no. 1 (1981): 16-17.

Figures

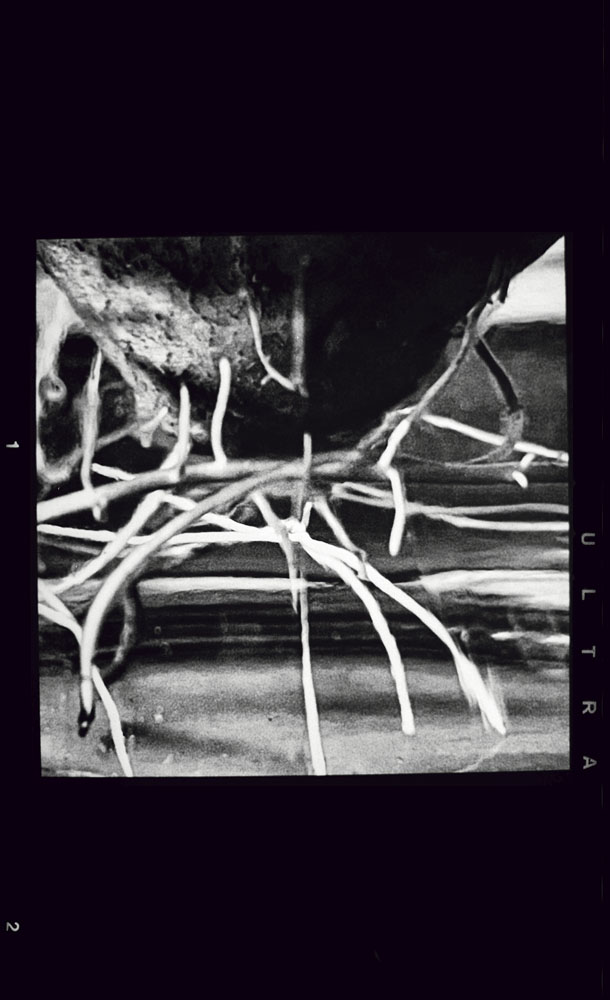

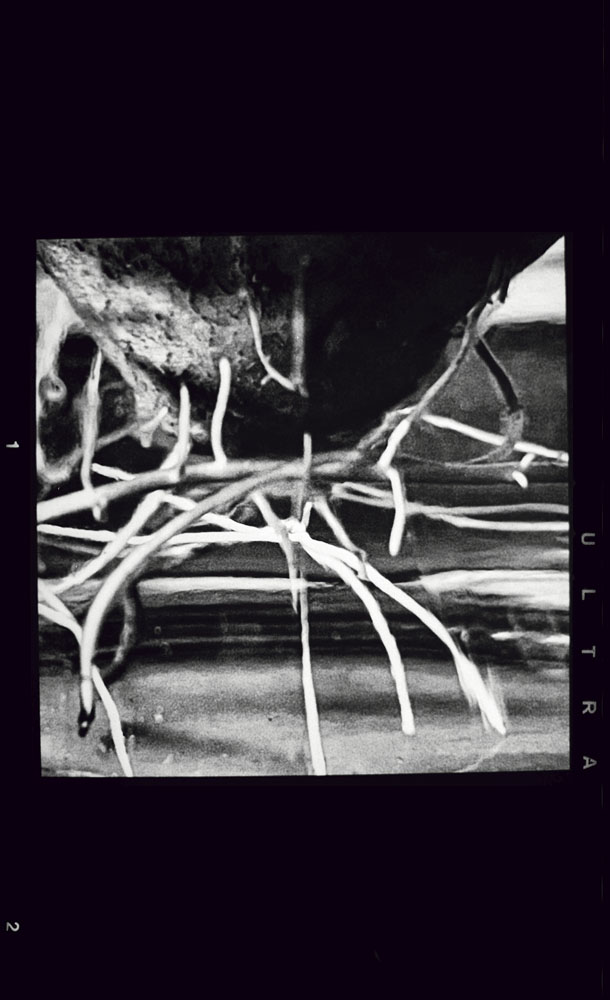

- “On my Own in Berlin.” From Peter Wendel, Kostymen sys i det tysta / The Suit is Sewn in Silence (Stockholm: Journal, 2022),

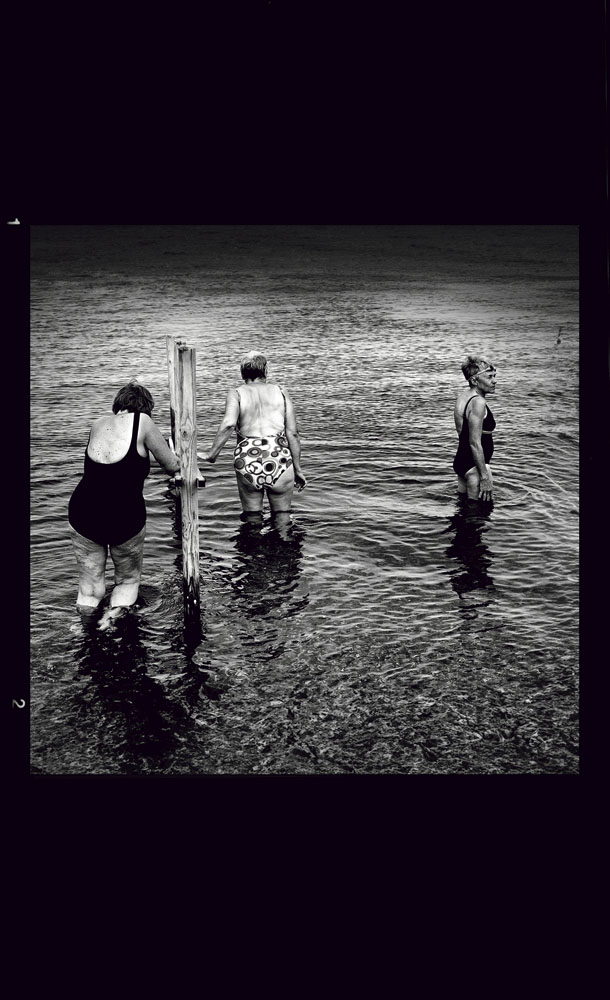

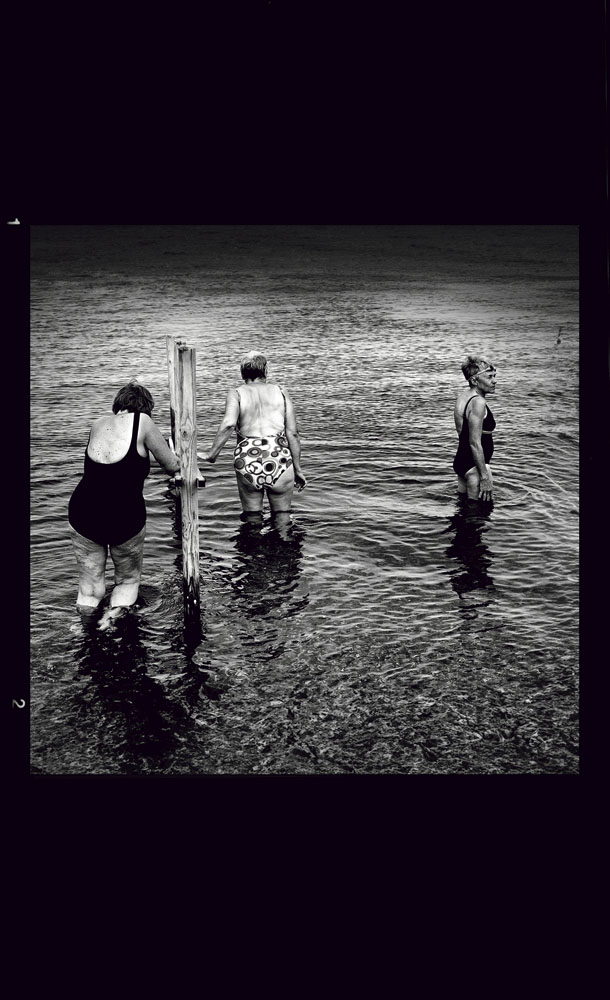

- “Sunday Bath.” From Peter Wendel, Kostymen sys i det tysta / The Suit is Sewn in Silence (Stockholm: Journal, 2022),

- “Breakfast View in Berlin.” From Peter Wendel, Kostymen sys i det tysta / The Suit is Sewn in Silence (Stockholm: Journal, 2022),