Ears for the Eyes: Auditory Perception through Photography

Photography is often claimed to be a silent medium that freezes numerous moments of our lives and resonates quietness. Jean Baudrillard stated in his essay For Illusion Isn’t the Opposite of Reality… (1999) that the silence of the photograph is “one of the most precious qualities”.[i] Regardless of what is happening in the moment of taking a photograph i.e. “whatever the noise and the violence around them, photographs return objects to a state of stillness and silence.”[ii]Attention is given to the composition and precise stagnancy of movement that is created. But it does not mean that all photographs may be perceived this way because photography is always enveloped in sounds.

There are many ways to visualise sound. You can burn sound, you can draw sound and you can convert sound to salt patterns. It is easy to indulge in the process of making such visualising experiments with, for example, tutorials from YouTube channels. It is also undemanding to photograph a sound event: a musician’s performance, a firework explosion or a windy day. So far, we can only create recordings of two senses, sound and sight, and there is a similar property in recording both types – freezing a moment and capturing everything, regardless of what we wish. As the editors of Aperture state in their issue 224, titled Sounds: “Photography might be a silent medium, but in recording the experience of sound, these images turn up the volume.”[iii] In the next ten minutes, we will search for quiet photographs documenting sonic events and loud photographs that make our mind jump.

Imagine sun, wind and beach at any time of the year. I can already hear the waves in my mind, can you? There is something that makes me reimagine being on the beach when I think of the elements that bring this image together. The beach is such an ordinary yet powerful place where natural forces heighten our senses. The smell of sea and pine trees. The wind tousling hair and clothes. The sound of never-stopping waves with white foam approaching the coastline. I don’t even need to close my eyes to hear this natural setting. It’s already there in my mind.

Looking at photographs of sand dunes, pine trees and the sea’s waves makes me hear that environment. It is deeply embedded in my memory as a place that is never silent and never still. In search of loud photographs, I stumbled upon a vivid publication in the same Aperture issue on sounds, which gives an overview of how sound can be depicted using photography.[iv] A variety of approaches is introduced: long exposure photographs of a record player, headlight trails from loud, moving vehicles, photograms and cyanotypes of cassettes, moments of lightning and guns, musical instruments and screaming young teenagers. A particular photograph titled Sea Breeze (1978) by the American artist Suzanne R. Dworsky struck me as greatly powerful. It teleported my eyes and ears to my own nostalgic beach with a warming sun on my skin. The photograph is merely a close-up shot of a girl’s ear pierced with a colourful earring, messy hair, and the waves and beach in the background, but it was enough to bring back the memories of sounds from my own beach.

Such an immersive feeling evoked by photography leads to an understanding that this is, of course, an illusion. Only recently I came across the term phantom auditory phenomena (also referred to as auditory hallucinations), which are false perception of sounds including musical tones, words and sentences, and conditions such as tinnitus.[v] To my surprise, I found that there is no established link between the perception of photographs and phantom auditory phenomena. I believe that being able to hear a photograph is very much the same as to experience auditory illusions because there is no external sound stimulation, yet it can be perceived in our mind.

Baudrillard made a direct link between photography and silence, and I agree with him that some photographs do resonate stillness, particularly black and white and modestly sized images. However, I am certain that when it comes to colours, there are screaming colours and there are calm or rather quiet colours. What does it mean? Colour properties have to do with the attention we give and how we focus on objects, meaning that some colours attract attention faster than others. They are seen quicker in one’s peripheral vision. Thus, if a photograph attracts the eye, i.e. consists of bright colours, it may be screaming at you. But if it lacks contrast and appears no different to the reality we see when we peer through the window, then I would perceive it as a quiet image. For example, take the well-known photograph by William Eggleston titled The Red Ceiling (1973) that has also become the cover image for the album Radio City (1974) by the band Big Star. This photograph is absolutely screaming at me with cacophonic sax and piano sounds. To this day, I clearly remember my reaction when I first saw this photograph: what a beautiful, screaming red!

Even noise, that is of sound origin, is a common term in photography. Noise is unwanted auditory disruption, and in digital photography, the same term is used for referring to visual flaws caused by the image sensor. Meanwhile, in analogue photography, noise refers to the photographic grain that is a characteristic of photographic films.[vi] Unwanted information during the recording is something that sound and photography share. Note that by inquiring into this area, I learned that the relation between sound and photography is not frequently discussed and remains underexplored.

Even if not all of us might hear photographs enriched with specific musical instruments, our brains are prepared to listen as we look at still images. A team of Italian scientists has conducted research on whether vision can trigger our auditory perception, publishing their results in a paper, titled When a photograph can be heard: Vision activates the auditory cortex within 110 ms.[vii] Their findings indicate that our ears are indeed prepared to hear sounds as we look at images. I believe that it is a matter of how we think about images and what particular senses we connect together. In the introduction of the paper, the scientists refer to silent movies and the ability of the audience to effortlessly recognise particular sound events and fill the lacking sound with their imagination. Even though silent movies were always accompanied by live piano music, and the theatre was never silent, the audience experienced all the sounds that were known to them. Going back to the photograph of the beach by Dworsky, it means that if we have been on a beach, we know how it sounds; therefore, we hear it.

I would like to argue that uncommon sounds and visual representations of them are meaningless if we have never heard them before. Let’s approach sound from a different perspective. The renowned Japanese photographer Naoya Hatakeyama explores human influence on nature. He focuses on the imagery derived from sound events; in other words, explosive blasts frozen by the camera’s shutter. Explosions, as we know them, are painfully loud, but his photographs of limestone scattering in all possible directions are somehow quiet. I have not seen rocks or limestone explode in such a way; as a result, the photographs from Hatakeyama’s series Blast (1995) are silent to me. This is not only because of my unfamiliarity with the subject but also because there is no possible way to witness an explosion within a fraction of a millisecond through the human eye alone. Only photography and slow-motion film can show this to us. And even then, sound is softened or non-existent. Yes, explosions are loud, but not when a fraction of them is perceived to be frozen in time and space through photography.

The American philosopher Robert Pasnau convincingly argues that sounds are properties of objects and hearing is a locational sense, making sounds dependent on their source.[viii] Manifestly, sounds are effects of sources: for example, we say that we hear the cat because we hear the sound it produces. No wonder that when we hear an explosion, we look, and search for its source. Usually we experience sounds as sounds of something and they are claimed to be this way, but what happens when a visual property is imposed on us accompanied by a sound, and we are forced to believe it is the true sound source?

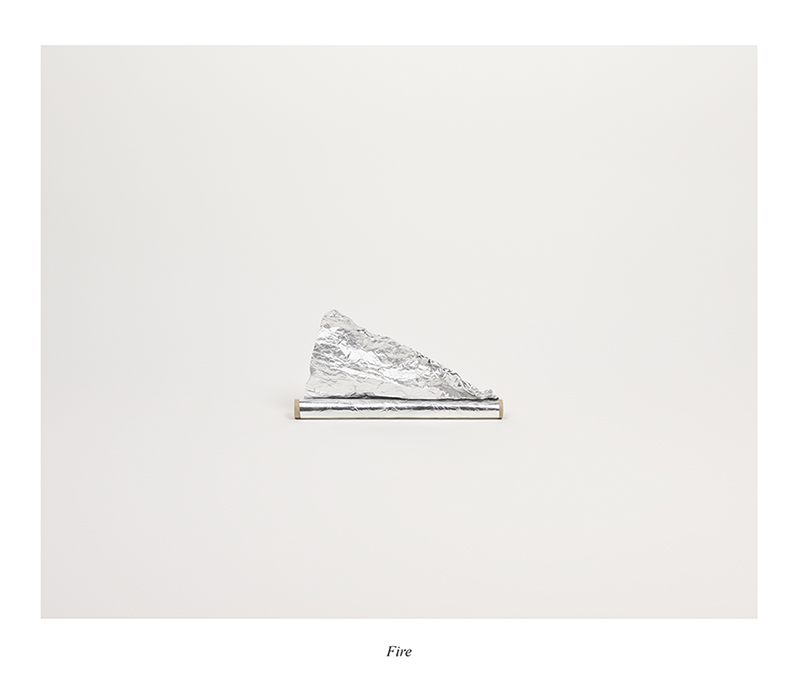

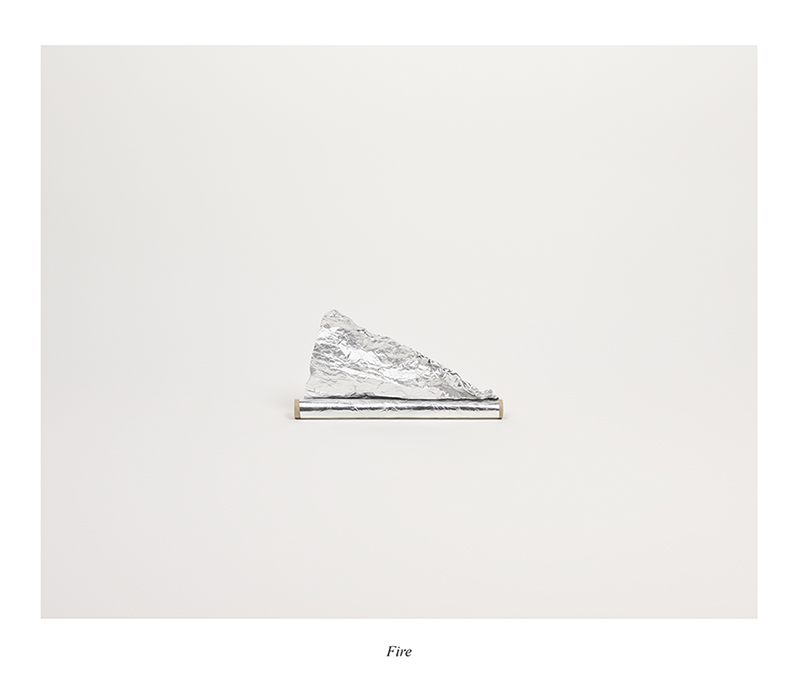

I would like to answer this question by introducing a project called Foley Objects (2013) by Finnish artist Jonna Kina. It consists of thirty photographs with captions that at first glance do not seem to relate to each other. However, after observing the series for some time, it becomes evident that the photographs display objects that create specific sounds that are required in movie production. Our ears are so used to hearing grass rustling in movies that we barely question the sound source of it. I find it interesting to connect this to aforementioned philosopher Pasnau’s thoughts, because Kina’s work reveals something hidden behind the making of movies. It also forces us to rethink what we know of sound and how visualised materiality in photography can become audible. Let’s get back to the example of how hearing a cat means hearing the sound that cat produces. When looking at a photograph, we often forget the physicality of it, and refer to the cat in the photograph as the primary element whereas in fact, it is a two-dimensional reproduction of a cat through photography.

Let’s think further towards recording sonic events in photography and how auditory perception can influence colour. For an enhancement of emotions, such as sadness and joy, the use of a specific colour palette and contrast of light and darkness have been widely used by artists. The Taiwanese artist Yehlin Lee creates his own system of colours and Taiwanese aesthetics in his project Raw Soul (2011-2017), which concluded in the release of a book under the same title in 2017. Photographed on his home island, Lee’s process involves looking for aural aesthetics with vision. The series describes the feeling of and relation between musical timbres and colour tones, and the parallels between melodies and lines.[ix] Lee’s approach is very intuitive. In his book, Lee writes: “Like a submarine, I wait for the inner background noise to quiet down. When sound is heard from within, I click the shutter.”[x] This is a poetic approach to reflect on the national landscape that is dependent on the mood and resonance of sounds. The imagery can be freely interpreted and understood as waiting for a signal in order to take a photograph i.e. to portray a specific sentiment and sound.

To conclude, it is evident that photography and sound have a lot in common, but this relationship lacks exploration and in-depth research. Both photographic and sound recordings operate as representations of reality yet are often disregarded as such. Both are trapped in the duration of time. We often emphasize the recognition of the object or sound, rather than the fact that this is merely a depiction and a recording. We do not appreciate the idea of representation because this is not what we see and hear. We look at a cat, not a photograph of a cat. We hear thunder, not a recording of foley objects which sounds like thunder. Even though photography is primarily a visual medium, I am sure that certain imagery can evoke phantom auditory phenomena in our mind. Even several of the terms used in photography are related to sound theory and auditory perception. However, there is so far no convincing link made through research in art. We cannot perceive surroundings through purely one sense without the interposition of the other senses. The six examples given in this article provide just a beginning towards an exploration of photographs that induce auditory hallucinations, photographs that are documented sonic events, and photographs that are representations of objects that suggest a specific sound. Let’s open up our eyes with our ears.

References:

[i] Baudrillard, J. “For Illusion Isn’t The Opposite of Reality…”. In Jean Baudrillard : Fotografien : 1985-1998 [Ausstellung 9.1.-14.2. 1999, Neue Galerie Graz Am Johanneum]. Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz. 1999. p.135.

[ii] Ibid. p.135.

[iii] Famighetti, M., Wattenberg, B. ‘Editors‘ note‘. Aperture. Issue 224 (Sounds). 2016. p.9.

[iv] Aperture. Issue 224 (Sounds). 2016. p.116-123.

[v] Wible, C. G. The Brain Bases of Phantom Auditory Phenomena: From Tinnitus to Hearing Voices. Semin Hear 2012; 33(03): 295-304. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1315728

[vi] Boncelet C. Image Noise Models. In Bovik A. C. Handbook of Image and Video Processing. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-119792-6.X5062-1

[vii] Proverbio, A., D’Aniello, G., Adorni, R. et al. When a photograph can be heard: Vision activates the auditory cortex within 110 ms. Sci Rep 1, 54. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00054

[viii] Pasnau, R. What is Sound? The Philosophical Quarterly 49, 196 (1999), pp. 309-324. doi: 10.1111/14679213.00144.

[ix] https://medium.com/stories-behind-photography/see-the-sound-in-photography-looking-for-sound-art-aesthetics-within-the-sense-of-vision-8ef92b2b4e1 (Accessed 2 April 2020)

[x] Lee Y. Raw Soul. Akaaka Art Publishing, Inc: Kyoto. 2017. p.117.