Footprints.

The river right next to my old school separates Germany from Austria and still brings floods every spring when the snow melts in the Alps, carrying whole trees, parts of small houses or bodies downstream. We often watched the hustle and bustle from the windows of our classrooms and always called out when we saw something unusual. Sometimes a large trees smashed into the bridge connecting the two countries.

When I moved to Berlin to study and to leave that politically very conservative region, I also left a part of myself behind without realizing it. During these years I was constantly going into the woods in the surrounding area to fill this hole and be with myself away from the noisy and stressful city that I loved. One day I saw a picture of ‚Rapadalen‘, a valley with many lakes and branched rivers in northern Sweden surrounded by rocky mountains. I was fascinated by the beauty and booked a trip there. I hiked through the northern Swedish forests in jeans and sneakers and initially regretted my decision that I made as a classic city dweller. The nights were cold even in summer. On the second day my shoes dissolved. But I didn’t want to admit failure and kept on walking. Back and forth, uphill and downhill, paddling across the lakes and passing through several rivers. Finally and after some more days of hiking, I passed the valley and went up the mountains on the other side again. I pitched my tent and headed towards the sunset in the direction of Skierffe’s top, the striking mountain that borders the valley. Once there, I sat down on a rock with hundreds of meters of vertical drop in front of me. There was no noise to hear, it was almost completely quiet. Only a few insects buzzed around me. I stared into the distance and at the valley for hours until night finally fell after these long arctic summer days. The moon and the infinite amount of stars lit up the valley while a herd of reindeer was grazing not far away. They seem quite unimpressed by me. For the first time in my life, I saw a landscape where there was nothing (hu)man-made visible at all and where nature at least seemed wild. “Wow…”, I thought, “this is what the world would look like if there were no people having impact on the environment.”

I took a detour and settled in Cologne just a few weeks before the most expensive police operation in the history of the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia. This event is today known as the bitterest defeat for politically influential and powerful companies in Germany ever since. The ‘Hambach Forest’, a small and inconspicuous forest not far from Cologne, had been occupied by environmental activists years before, but the conflict over its future reached its climax that year and led to weeks of “fighting” and standing against a huge corporation and police departments from all over the country acting in its favor. The company wanted to clear the forest, a 10,000-year-old ecosystem, home to unique animal and plant species, in order to mine lignite and thus expand the diameter of the largest artificial hole in Europe. Sometimes, when the excavators – as tall as the Gothia towers in Gothenburg – stirred up the dust in the air, it was impossible to see the other edge of it.

At that time, I still had a press card and was able to move freely in by police cordoned-off areas and which also protected me from the arbitrariness of the state authorities. I served as a messenger between the people who had already spent days isolated in the trees and provided them with news and food. I identified with them. When the verdict of the Supreme Court was announced and the measures were immediately suspended, a huge burden fell from us. The barriers were lifted and tens of thousands of people poured into the small forest. It was a strange atmosphere, somehow spooky and happy at the same time. We were wounded and exhausted. All of us. Not just those who were holding out in the trees, but also those who had been protesting every day in front of the barriers. We sat down on the granulated wood left behind by the heavy machinery used to clear the land. People brought their guitars and played melancholic music as the first leaves fell to the ground in the light winds of fall. “It’s over,” we thought. And it really was. We had tears in our eyes and couldn’t believe it.

The courts had condemned the police operation – initiated by the then Prime Minister, who has a professional past with the mining company – and the eviction of the tree houses as well as the arrest of activists as unconstitutional.

Today I live in Skåne, in Lund, an area is known for its agricultural landscapes and its smaller mines. I enjoy the train rides to the University in Gothenburg. The rails run along the cost and sometimes very close to the sea. When I am traveling early in the morning and it starts getting brighter, the sun immerses the landscapes, the sea and its rocky islands pastel tones intensively. The train then passes a factory north of Varberg that is often surrounded by thick clouds even when the rest of the sky is blue. One day last fall I noticed a freight train loaded with logs waiting on a track parallel to ours. As we passed it, it seemed to have no end. I wondered why it was standing there, where the trunks came from and what it might look like at its origin now. I found out online that the factory is Sweden’s largest sawmill and that only 0.3% of Sweden’s many forests are considered primary forests.(1) Does Rapadalen count as part of this 0.3%, I wondered? Apparently not. At least it was not included in a map of ‘primary forests in Sweden’.(2)

In the book ‚No mine in Gallok – Ecocide and colonialism in Swedish occupied Sápmi‘ the storyteller and practitioner of samic jojk-singing, Juhán Niil Stålka, writes:

“So it began, and so it continues: every inch of land you passed when you came here [to Gállok], […], it doesn’t matter which way you took, from the coast or the inland, everything is a plantation, […]. They clear-cut everything, completely destroyed the old forest and grow only one species. In the south it is spruce, here it is pine. […] And the Swedes that come to this area now say: ‘Oh what a beautiful forest’. […] They don’t see the difference between a real forest and a plantation. The biggest species we have are fungi. You don’t see it, it’s under us, you only see the fruit. When you clear-cut, everything gets killed. When it gets killed it rots and leaches methane gas. It is dreadful. It is the Western economics that boosts this so-called ‚development’”.

In my artistic practice I try to make people see the privileges and natural resources many of us are born with, which we did not do anything to gain and do nothing to protect or pass on. We need to find new ways to live more consciously to coexist as equals, humans, insects and nature. In my photographic work I attempt to at least minimize the effects of my own ‘footprints’ as well as motivating its viewers to do the same.

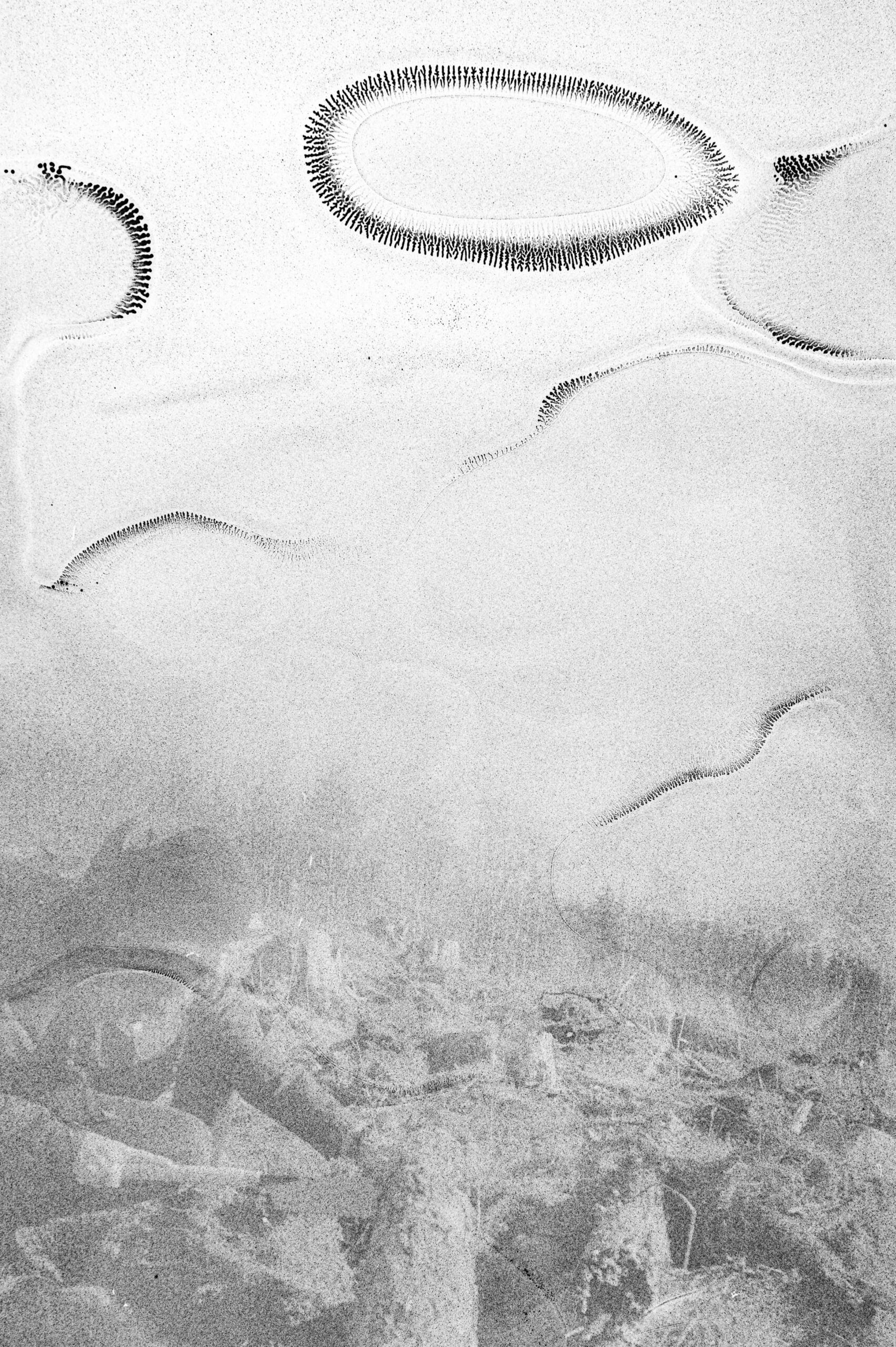

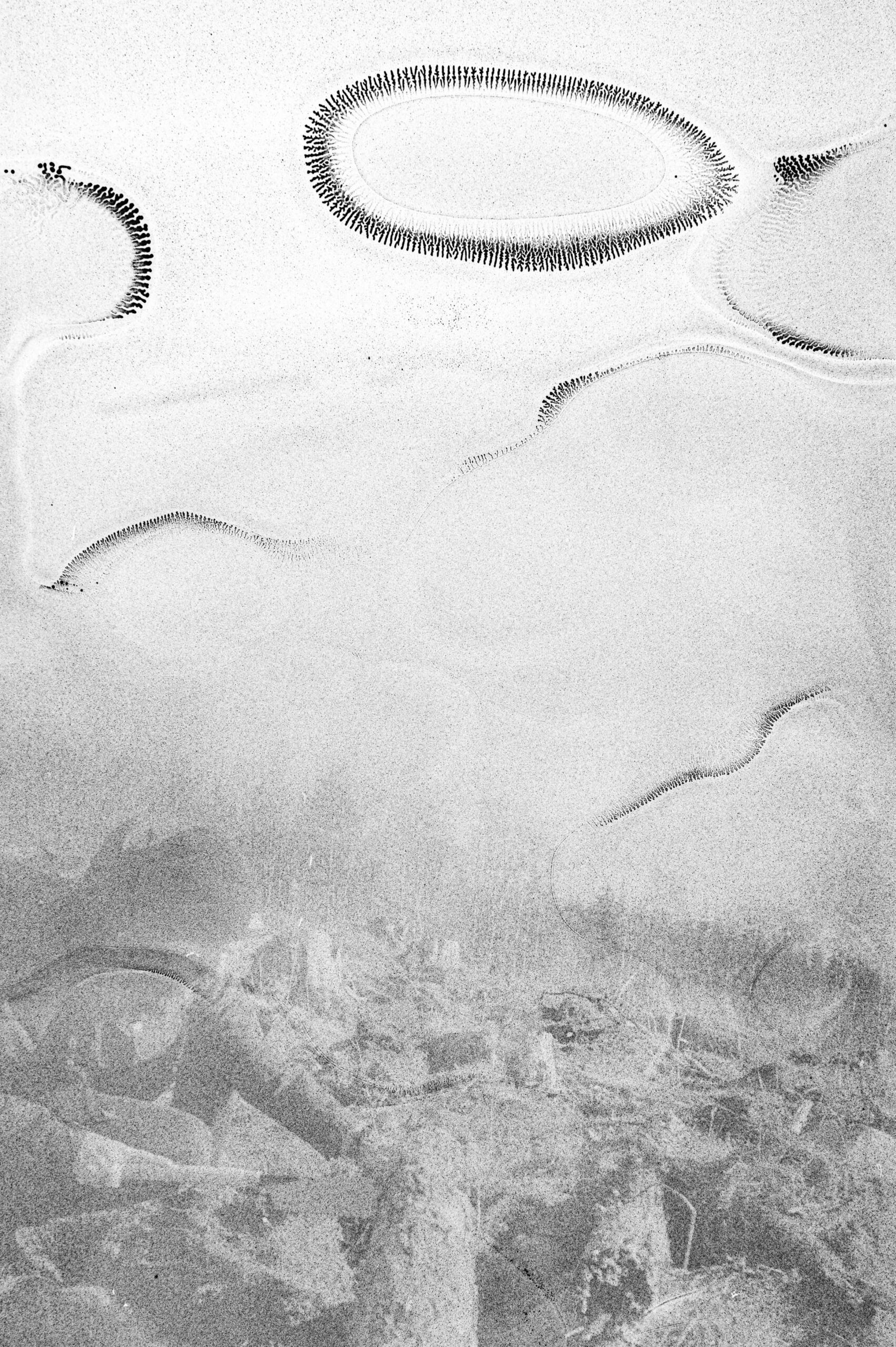

In parts of the work I am striving into a collaboration with nature in which both, nature and myself, are contributing to the final result. This is being implemented through portraying various forests and allowing an individual compound of biochemical substances affect the analog film. These substances are found and collected in the respective forested areas and consist of liquids from characteristic plants and water sources. At ‚Kullaberg’, a peninsula in the north west of Skåne I found an immense amount of honeysuckle and bellflowers. Related to the vicinity of the sea the found water was more salty than in other regions while some of the water found in a creek at ‚Skrylle‘, a forest east of Lund, was polluted. Additionly, its blueberries made the mixture’s PH more acidic than in average. In some months of the year wood anemones and celandines are omnipresent at ‚Dalby Söderskog’, Europe’s smallest national park located close to ‚Skrylle‘. Those and many more plants, such as nettles, orchids, different kinds of mushrooms and berries had been collected to dissolve the biochemicals and let them affect the analog film. As a general result, colors run, a part of the film surface had been destroyed or a pattern was drawn on it individually like fingerprints. This method leaves some of the visual design over nature’s representation by itself. The outcome is unpredictable and visualizes the individual character of each ecosystem.

(1) Högskolan i Gävle, „Dofter avslöjar vilken skog som är viktigast att bevara“, www.forskning.se, visiting page on 2024-02-20, https:// www.forskning.se/2020/08/10/dofter-avslojar-vilken-skog-som-ar-viktigast-att-bevara/#:~:text=I Sverige finns 85 000,exempel Tyresta nationalpark utanför Stockholm.

(2) Ahlström, Anders & Jong, Geerte & Nijland, Wiebe & Tagesson, Torbern, „Primary productivity of managed and pristine forests in Sweden“, Environmental Research Letters, visiting page on 2024-02-20, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Mapped-primary-forests- in-Sweden-Blue-markers-indicate-primary-forests-that-are-included_fig1_342023824

(3) Minority World refers to economically more privileged countries