Home, your piece of the world, the land underneath you and the sky above you.

A discussion on the use of the uncanny in the video piece “Here after” (2004) by Patrick Jolley, Rebecca Trost and Inger Lise Hansen

By Aissa Lopez MFA

May 2018

Introduction

In my artistic practice, I have been considering our relationship with the architectural spaces we inhabit, particularly the house/home. I have utilized the uncanny as a method of exploration, as a way to articulate my conceptual concerns and demonstrate how these spaces as the background set of our everyday lives can become loaded with meaning.

An examination of contemporary artists’ use of the domestic space and the uncanny in their work was the subject of my Master’s thesis. One of those artists was Patrick Jolley (b.1964-d.2012).1 I was interested to examine his work further, as there has not been much written on his practice and I felt I could contribute to the understanding/ conversation. Having also come from Ireland there is a shared cultural heritage and understanding of the history of what “home” means in an Irish context, but the strength of Jolley’s pieces mean they work beyond the colloquial. The piece “Here after”2 (2004) was made in collaboration with Rebecca Trost and Inger Lise Hansen (b.1963). The socio-political concerns of this work and the modern anxieties they raise are as relevant as they were fourteen years ago, when the piece was first exhibited.

In this article, the aforementioned domestic space is being considered not just as the actual architectural one, that we see in “Here after”, but also as a conceptual space.3 The domestic as family home, as a site for memory, the mundane background to our everyday lives; where our roles in and relationships with our society can be shaped, where the dynamics of what is public and private can be played out and where memory and the repressed can resurface.

The artists use the familiarity of the domestic space and/or its objects in this work and disrupt them, utilising the uncanny as a meta-form and metaphor in order to expose and problematize contemporary cultural and socio-political norms/mores connected with to the home.

The Uncanny

By deciding to write about a piece which utilises the uncanny as a means of communicating its conceptual concerns, one is put in the position of explaining what is meant by the word uncanny. The uncanny has been interpreted and reinterpreted and the various meanings have had differing applications across a number of fields. It is necessary to give somewhat of an explanation on the aspects of the uncanny that are relevant to the reading of “Here after” in order to discuss the work successfully.

Freud’s essay “The Uncanny” (1919)4 has become a seminal work in discussing what the uncanny can be understood to be or described as; it has become almost a requirement that it be mentioned when picking apart an understanding of the uncanny, even in the briefest of fashions. Freud drew on E.T.A Hoffmann’s story “The Sandman” (1816) as way to explain his psychological interpretation of the uncanny. Hoffmann’s unsettling story comes out of gothic literary traditions and that have been positioned in relation to Edmund Burke’s “Terror sublime”.5

Freud spends a significant amount of his essay attempting to form a dictionary-like definition and origin to the term “uncanny” (“The Uncanny” (1919) p.123-124). He takes the German word “heimlich” or homely/ intimate as a counterpoint to “das unheimliche”, though generally translated as uncanny or unhomely the meaning is a little more nuanced, it is not exactly an opposite of homely, but a sense of strangeness or of the unknown contained within the familiar, intimate or homely. In Freud’s effort to explain and understand the uncanny through Hoffmann’s work he moves the “spooky”, unsettling and unexplained from the realm of the supernatural to the psychological.

Ernst Jentsch’s explanation of the uncanny- in his essay – “On the Psychology of the Uncanny” (1906) – rests on the individual’s inability to immediately identify or categorize something they encounter (which we can fit in with our contemporary cultural understandings e.g. ghosts which are the dead and gone/past yet appear in the present, and therefore defy categorisation). Freud theorised that the anxiety or disturbing sense of the uncanny that can come from this cognitive dissonance or an inability to trust one’s own judgement is an aspect, but not all that there is to the uncanny. He recognizes (using the example from Hoffmann’s “The Sandman” of the automaton) that it is unsettlingly when something is similar to another, familiar thing esp. when it is life-like but not alive. He expands this to include the double/doppelgänger, repetition and the return (as connected to desire, the drive and the death drive)>6. The uncanny experience is seen by Freud to come from the triggering of a repressed emotion/trauma that attempts to resurface or primitive beliefs (e.g. superstitions, ghosts and spirits) that reassert themselves albeit temporarily7. Repetition and the repressed returning are aspects of the uncanny, I have found and will demonstrate are exploited by Jolley, Trost and Hansen in their piece “Here After” in order to successfully communicate their conceptual concerns.

The philosopher Friedrich Schelling’s definition of the “unheimlich” fits well with “Here after’s” use of the uncanny. Schelling describes it as such:

“everything that was meant to remain secret and hidden and has come into the open.”8

Louis Vax’s criticism of Freud’s “The Uncanny” (1919) which Anneleen Masschelein discusses in her work “The Unconcept. The Freudian Uncanny in Late Twentieth Century Theory” (2011) connects the uncanny with notions of the fantastic, the strange or the eerie. He describes the strange as “unstable and dynamic” it seduces and repels (ibid. p.60 par.2 & 3) He critiques Freud’s attempts to define and dissect the uncanny experience, he considered the uncanny ambivalent in nature, that the experience of it changes context with the experiencing subject. (ibid p.63, par.2)9 Within the work “Here after” this is a relevant point to emphasise. The uncanny can exist between categories, vacillating between horror, the abject, the strange and the eerie, the spooky and the haunting10. It can be seductive in the curiosity and mystery it raises, it can be alluring in its’ aesthetic quality11. The uncanny changing with the experiencing subject, is something that needs to be addressed, in the piece discussed here, this is tackled by basing the work in domestic space, there is a common ground for interpretation. Jolley, Hansen and Trost use the tropes of the uncanny we can recognise from the studies of it in psychology, critical theory and from popular culture. Though there is a subjective experience to be had in the interaction and reading of the work, by the individual viewer, there is a common cultural code for understanding the work, embedded in the piece.

Ernst’s and Freud’s essays have been debated and discussed within psychology and the arts particularly in literary criticism and the study of horror and science fiction. There is much that can be read and said on the subject.12 But if we parse the uncanny as utilised generally in the visual arts, there is a potential advantage. The artwork does not have to explain the uncanny to the viewer but can show it, the artwork can potentially generate the feeling of “uncanniness” in the viewer, it can refer/elucidate visually to it without literally defining it by (re)-presenting the uncanny allowing room for the viewer to (re)-imagine what the uncanny is for them. Once the art work successfully does this the piece becomes open to a deeper reading, the layers of meaning can be revealed as the viewer asks themselves why is the uncanny being used? Why has the artist chosen to disrupt the norm? What does the piece wish to communicate by doing this?

The Home is haunted.“Here After” (2004)

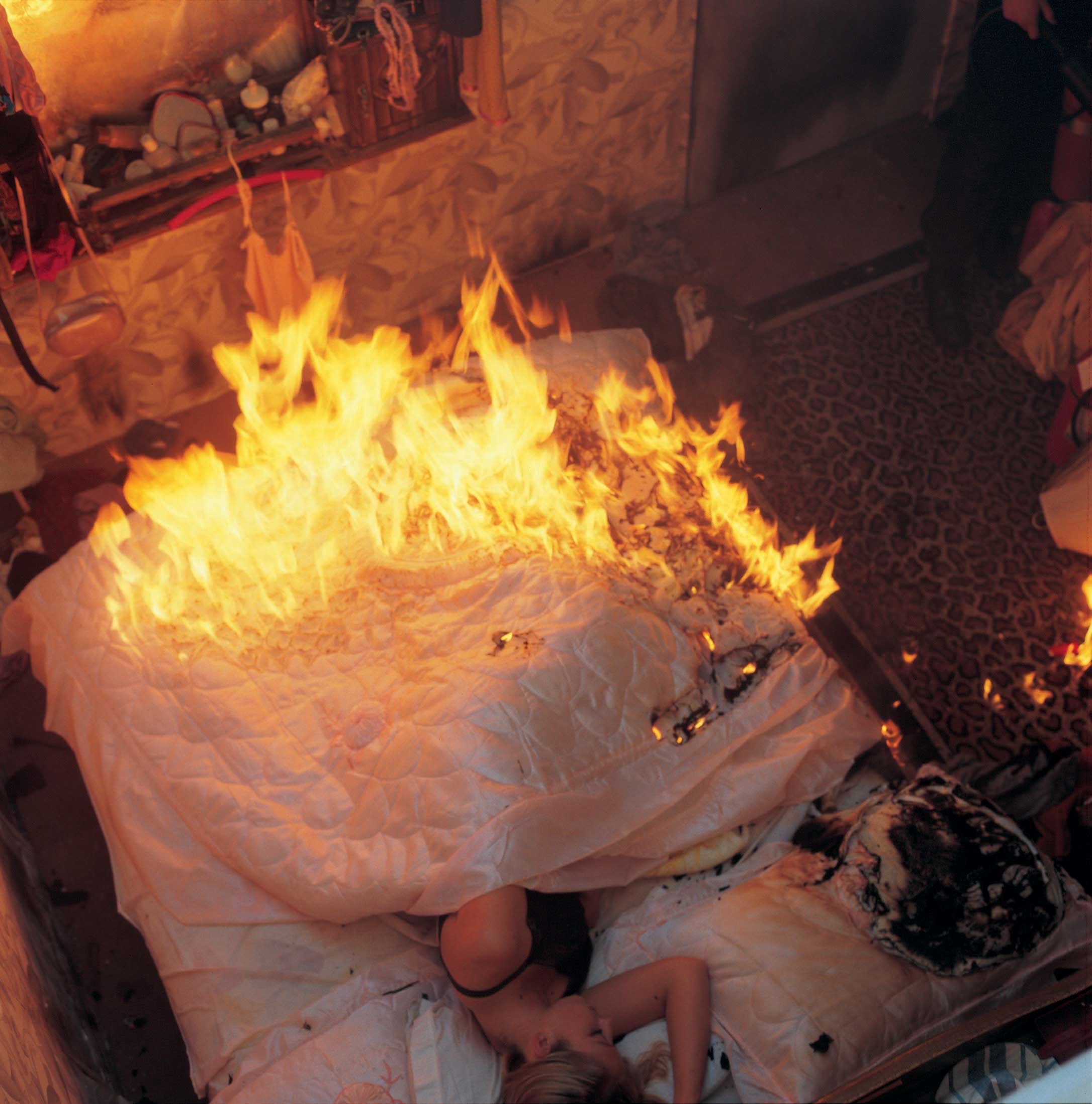

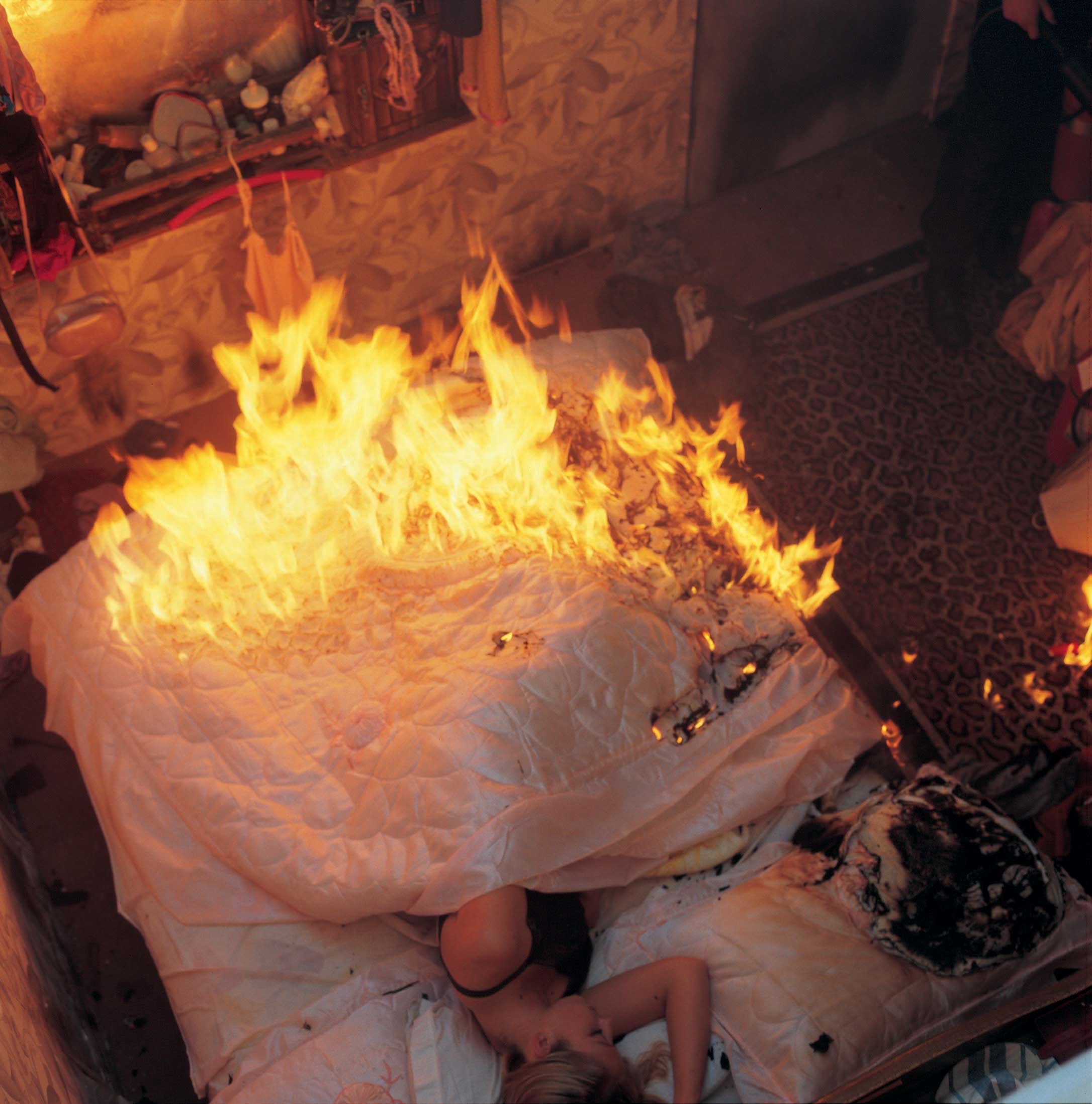

Irish artist Patrick Jolley’s (b.1964 – d.2012) had a history of dealing with the domestic space and the uncanny in both his photographic and film work. His films “Drowning room” (2000) and “Burn” (2002)13 (see fig.1&2), made in collaboration with American artist Reynold Reynolds (b.1966) both deal with the domestic, surreal, abject and the uncanny.

Here after(2004) is a black & white super 8 & 16mm short film which was made by Jolley in collaboration with Norwegian artist Inger Lise Hansen (b.1963) and German artist Rebecca Trost.14 Rebecca Trost had previously worked with Jolley and Reynolds on “Burn” (2002) as part of the production team and as cinematographer on their film “Sugar” (200515). Hansen shows in her work a similar sensitivity to Jolley for how the places we inhabit are loaded with meaning; and a shared interest in playing with time to build tension and create atmosphere in her pieces, you could say this is true to all film makers, though this is emphasized by Hansen’s use of stop go animation and time lapse which can be seen in the 16mm film piece “Hus” (1998)16 and in “Here after”.

The medium of film, like the photograph, can be said to have an inherent uncanniness to it. The film being a copy, imitation, double or repetition, capturing real, moving, life and replaying it back to us, the apparition of the past appearing in the present, all of which have ties to the concepts of the uncanny I have discussed previously.

This work is an example of the heimlich and unheimlich being utilised to full effect, problematizing the themes of nostalgia, the hauntological and the return. There are references to the imitation and the automaton also of the haunted house, of architecture being a vehicle for the uncanny17 which are seen in both Ernst Jentsch’s and Sigmund Freud’s essays on the uncanny.18 This is demonstrated in Here afteras repeatedly objects of the home seem to gain life and move of their own volition. The work continues to disturb the familiarity of the domestic space portraying its life and decay after being abandoned by the inhabitants. Yet their story and what they can stand for is told in and by their absence. These aspects all lend to the unsettling atmosphere and play with our modern interpretations of the haunted house and the psychological tropes of the uncanny as explored in Freud’s essay.

The work goes further than being a piece solely about the uncanny itself, the uncanny is used as a means to communicate the piece’s conceptual concerns. The site of the work is key to the other readings of the piece. It was made as part of “Breaking Ground” – the Per Cent for Art program for Ballymun Regeneration Ltd. in Dublin, Ireland. This scheme existed between 2002 and 2009 and various art projects ran to mark the impending demolition of Ballymun’s mid 1960’s tower blocks. The work was made in the Shangan tower block, was originally shown in the nearby Eamonn Ceannt Tower. The films were projected onto the walls and other surfaces of the abandoned flats and the sound was piped through the rooms. After the exhibition, the permanent artwork of the twelve-minute film Here afterwas made.

Ballymun was built as a solution to the social housing crisis in Dublin at the time, it was built with all the optimism that other similar projects were constructed around Europe. It quickly transpired to be far from the imagined utopia; as a result of the lack of local facilities, transport links and the city council poorly maintaining the tower blocks. The housing was not a mix of state owned/public and private but purely that of people who could not afford a home otherwise. These small flats were cold, damp and soon mould filled. The area became terribly affected by drug abuse and crime. People living there became trapped, other social housing rarely available and their economic conditions making it almost impossible to move elsewhere. The word Ballymun became synonymous in Irish society with destitution, a place to avoid, a place that if seen on your CV prejudiced people against you as an applicant. There was a long campaign for improvements by the Ballymun community residents, which turned into a campaign for their demolition and new housing to be provided, eventually happening in the early two thousands.19

Here aftershould also be seen in the wider context of the history of house or home in Ireland, which has long been a contested space. During the time of occupation and colonialism where the foreign landlord had to be paid their inflated rents, often ending in eviction, the idea of home was a fragile one. This sense of fragility was carried on to the impoverished tenements found in Irish cities as recently as the 1960s. The Irish’s stereotypical idea of a home is one you own, a house, with a bit of land, this possibly harks back to colonialism or from a traditionally rural farming heritage. Owning your home in Ireland means, perhaps naively, a secure home.20 There is not a tradition of long term renting like some other European countries nor are there the state controls that would make this a viable option. Therefore, the landless rented flats of Ballymun failed to meet the ideal standards in more ways than the obviously inferior construction and poor living conditions.

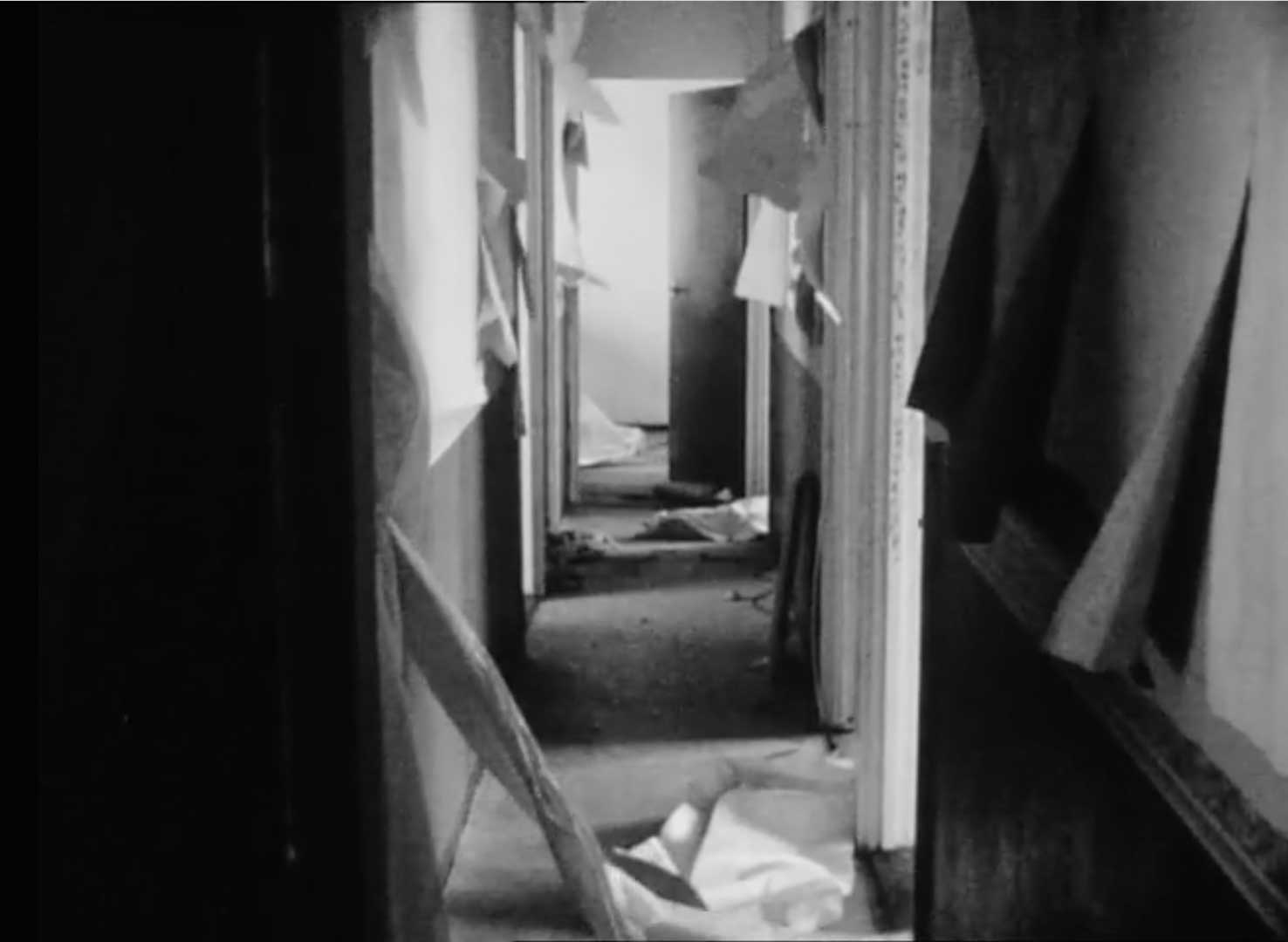

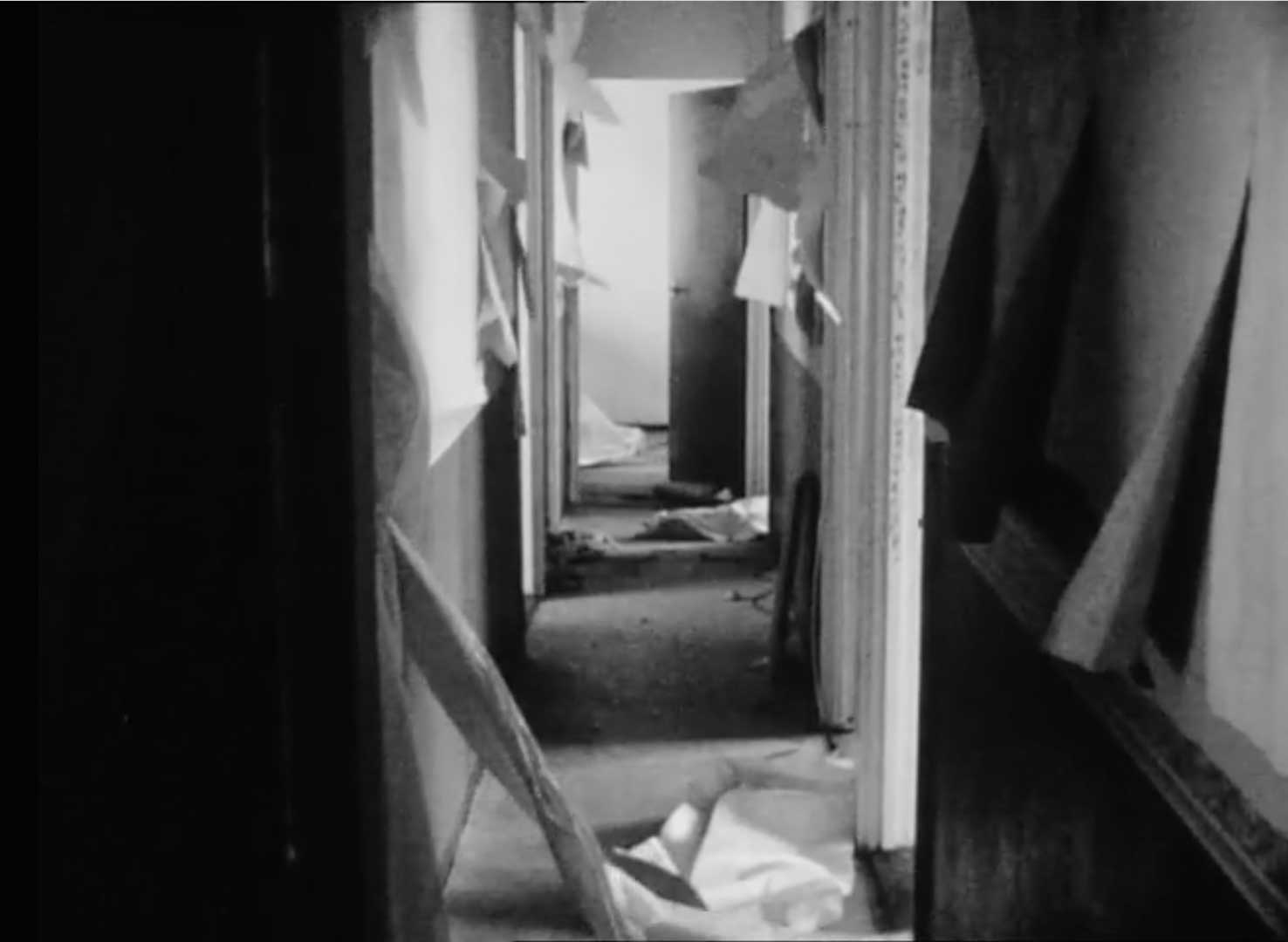

When we approach a reading of “Here after” it is necessary to keep this context in mind, what Ballymun’s apartment blocks have come to symbolize. Jolley aware of this opens Here afterwith a shot of the towers, derelict and austere, there are quick edits as we look up at them, a grey sky the backdrop (fig.3). The sound (all recorded on site) is of the wind, an eerie atmosphere is built. The opening shot of the interiors is of a long corridor, reminiscent of a haunted gothic ruin, but instead of long flowing curtains we find peeling wallpaper blowing in the wind (fig.4).

The rules do not apply here, the familiar becomes disturbed. Time moves too slow objects falling taking a little longer than they should, then inexplicably too fast, light races across abandoned rooms, shadows like people move in hallways. Invisible forces enact violence on furniture and some pieces seem to age and decay before us. We have entered a space that does not behave as expected, and as the piece progresses it becomes more sinister, inanimate objects seem to gain a life force, they breathe, mattresses plummet through ceilings, doors close by themselves, the building and furniture ooze unknown liquid, the floors open up and carpets seem to be eaten by these sinkholes, pulled into a void below. (fig.5, 6 &7)

The multiple mattresses and furniture that fall through ceilings emphasize the verticality of the spaces. Apartments stacked one over the other, multiple mattresses like multiple people existing literally on top of one another. This is not the ideal detached independent home, the space shared only with your intimate family, just the land underneath you and the sky above you.

Heidi Kaye writes in her essay The Gothic film(2015) about the persistence of gothic tales. That they may seem to be destined to be continually reborn to suit the fears and desires of each new period21 Jolley, Trost and Hansen utilise traditional techniques and aesthetic forms associated with the uncanny, the gothic tale of the haunted house that can be found in literature and horror movies in Here after.22

The nature of film itself can be seen as spectral, the past returned to haunt us, only coming to existence it the ghostly projection, an illusion of light. The artists’ choice to use black and white film adds to the dramatic lighting which helps create the haunting atmosphere. In referring to the history of black and white horror films, there is a doubling up of his use of the unheimlich, they stimulate our memories of previously experiencing horror and the uncanny, while we experience the uncanny again in the film Here after. They leave us doubly unsettled. In this they remind us we should already have been unsettled by Ballymun, in revealing the small living spaces and decrepit interiors they do not let us ignore how we failed a whole community. The work highlights our fears and anxieties about falling into poverty, of losing our homes and becoming one of the ‘abject’ lower classes, they point out the instability of our place in society and the flawed state systems that we are meant to be able to depend on.

The idea of home is haunted by its own fragility and by an ethereal, possibly, impossible ideal. In this piece, the artists problematize cleverly our relationship with the space/place. The camera observes for us, makes us look at this rejected/ abject site. From the generic forms of the tower blocks in the opening shots, each an austere twin of the other, to repeated scenes of decaying small rooms and corridors, the homogenized uniformity, the deindividualization of the living spaces is revealed. The work contains a menacing ambiance, mirroring the stereotypical opinions of the area.

They do not make it so simple though, the traces of people remind us people’s lives and homes were here, posters on a bedroom wall, a well-used couch with a pair of boots sitting nearby, as if the person has just walked out of the room. The artists received permission from the former tenants to use the flats and the objects left in the building; it is the repeated evidence and absence of people that is a pivotal part of the work. The objects are familiar, we can imagine people’s lives there or project ourselves into these now relatable spaces.

We recognize there are families’ memories held here; normally when we leave behind a home it continues, we can imagine others leading out their lives in the same spaces. But these were ill functioning homes, badly designed, perhaps doomed to end in destruction from the start and our witnessing their sped-up decay emphasizes their short life expectancy. The place and the objects now have a death sentence. We cannot have the comfortable nostalgia for a past home, or a beautiful abandoned ruin, these buildings have become symbols in Ireland for a failed state project that made the inhabitants’ lives harder.

There is a wider experience of these failed recent re-interpretations of Le Corbusier’s modernist apartment buildings which makes the work relatable outside of an Irish context.

The use of the unsettling atmosphere, the sense of the uncanny and the well-made aesthetic quality of the work makes the piece captivating and unnerving at times. The domestic space as heimlich and the exploration of it as unheimlich prompts us to consider our phenomenological and psychological relationship with the spaces we live in. Yet as I have explained here Jolley, Hansen and Trost go further, this work has a social and political comment to make. It makes us consider how our place in society determines the spaces we inhabit, our potential relationship with them and how they impact our quality of life and the fears and anxieties around this. The work does not want us to forget, or repress the memory of Ballymun, the buildings may be demolished but they can perpetually return in this film work. A reverent and a reminder of this ill-fated housing project and of the people who lived there.

Conclusion

Evident even on the most cursory of inspections is the fact Jolley, Trost & Hansen take the familiarity of the domestic space and/or its objects and disrupt them, thereby utilizing the uncanny to explore cultural and political norms/mores. As I scrutinized the work further it became clear that their successful use of the uncanny is integral to revealing the depth at which the aforementioned exploration occurs and is necessary for the communication of the conceptual concerns.

The house/ home as a protective world becomes penetrable by outside forces. The notion of domestic as a private space where the individual is hidden from public view, where we are possibly free to be ourselves, is revealed to be potentially an oppressive site, effected by socio-economic issues and political decisions, often beyond the individuals’ control. We are reminded that our position in a society determines the spaces we can inhabit and our potential relationship with them. The space that can be viewed a safe haven, becomes a trap. The idea of the ideal home becomes an un-ideal or imperfect one. Where our fears and anxieties around our ability or the possibility to maintain a home in its fundamental sense, as a dwelling that lends shelter and safety for our family, is examined.

On closer examination, the repeated use of absence and presence is an important aspect of the piece; the first obvious absence, we as viewers are asked to recognise, is the lack of the ideal home, seen in the opening shot of the imperfect abandoned tower block apartments, since demolished. What we do find left (or present) is made strange; with the clearly apparent absences the “missing” can be made present by this negation and there is often “an-other” presence alluded to by uncanny methods.

The disrupted reality created by the artists enables this, an absence/presence can be indicated and in the absence of language the visual artwork can attempt to subvert the symbolic and leave a gap for the repressed to return and potential a space for the Real to enter23.

A notable aspect of “Here after” is the use of repetition, particularly as it relates to the uncanny;24 which is integral to the work and is intelligently utilised by the artists to engage the viewer and structure their ability to problematize and communicate their theoretical issues, surrounding the contemporary domestic space and their larger socio-political concerns. In the repetition, the uncanny is emphasised and the habitual is reflected25. By presenting in the work, the same or similar differentiated repeats, after our initial experience of the piece’s unsettling aspects, we become familiar with the work; how to read it, even what to expect, but just like the uncanny, it is in the familiarity that the unfamiliar (hidden and repressed) is revealed and emphasised. The viewer is made look, to confront the conceptual concerns of the piece – the layers of possible meanings are uncovered and a deeper reading of the work can take place; elevating its ability to give voice to the ignored, repressed and underrepresented.

In “Here after” the artists take the familiar idea and aesthetic of the haunted house and repeat it back to us, changing it to a modern setting where the horrific conditions of this failed social housing are revealed. The motifs reoccur, multiple mattresses fall through spaces, beds and sofas breathe and quickly decay. They ask us to confront the fragility of our ability to maintain/ retain a home, for us to question the boundaries of our social divides and our trust in the governmental institutions that are meant to protect and provide for us. The film acts as a referent and a memento mori, to the buildings and imperfect homes that no longer exist; essentially, it can be played back to us, again and again, lest we forget26 this unsuccessful state project and the devastation it caused for the individuals and families who lived there.

In my discussion of “Here after” I have shown that the uncanny disruption of the domestic space, its objects and our relationship with it/them questions the habitual or the norm, the given, accepted or learned positions we hold in the society we live in. This questioning, this invitation for the viewer to reflect, is as powerful today as when it was first exhibited.

Jolley, Trost and Hansen cleverly use the aesthetic, atmosphere and the psychological tropes of the uncanny to communicate their theoretical interests. The uncanny and its unsettling effects do not have to remain stuck in a self-referential loop, repeatedly making us uncomfortable in familiar ways. These familiar ways, repeated, the signs and signifiers of the doppelganger, the automata, the unintentional return, and the haunted unheimlich house used in the work, can also be read as simulacrum. These simulacrum27, signifiers made empty by their reproduction, were ready to be filled by Jolley, Trost and Hansen with our modern socio-political issues, fears and anxieties; thereby problematizing our position and role in the cultures and ideologies which helped create them.

Afterword

I chose to discuss “Here after” as the conceptual concerns it raises still resonate today.

Furthermore, as mentioned in the introduction, there has not been a considerable amount written on Jolley’s body or work, I wanted to contribute to the understanding and possible conversations on his practice.

There is an onus on us, the viewers, to give “Here after” and the issues it raises serious consideration. The fact Ballymun was not a sole experiment, if we are to be generous we might say “not the only mistake” (if were attempting accuracy we would say “incompetence and wilful negligence”28). There are other areas in Ireland, in Dublin, Cork and Limerick that were built with similar lack of care, which continue to suffer a now familiar neglect. There are the many issues with housing for Travelers (a native ethic minority in Ireland) such the lack of safe Halting Sites29 and other places, where poverty and the states disregard for its citizens have combined to make basic living conditions and home a precarious possibility. The socio-political concerns and the anxieties surrounding the home, that the piece raises are as relevant today. The Grenfell Tower fire in London in 2017 tragically shows this governmentally sanctioned socio-economic neglect is not unique to Irish society30.

In the ten years since the economic downturn a succession of Irish governments and politicians have continued to mismanage Ireland’s housing market, both public and private31. It seems the issues that “Here After” raise are ones that we are doomed to be haunted by, a trauma being inflicted once again on another generation of Irish citizens, where the home in the basic sense as roof over your head, a dwelling that lends shelter and protection is not guaranteed by the state, currently being experienced by the 3,646 homeless children in Ireland.32 As the gap widens between the rich and the poor for many owning your own home is an impossibility and trying to keep the one you have is wrought with anxiety, an issue not only Ireland needs to face.33

List of illustrations

- Still from “Burn” (2002) Patrick Jolley and Reynold Reynolds. Source: Courtesy of Art Studio Reynolds. http://artstudioreynolds.com

- Still from “Burn” (2002) Patrick Jolley and Reynold Reynolds. Source: Courtesy of Art Studio Reynolds. http://artstudioreynolds.com

- Still from Here after(2004) Patrick Jolley, Hansen and Trost. Originally Sourced:https://vimeo.com/35882401

- Still from Here after(2004) Patrick Jolley, Hansen and Trost. Originally Sourced: https://vimeo.com/35882401

- Still from Here after(2004) Patrick Jolley, Hansen and Trost. Source: http://www.mexindex.ie/work/hereafter/

- Still from Here after(2004) Patrick Jolley, Hansen and Trost. Originally Sourced: https://vimeo.com/35882401

- Still from Here after(2004) Patrick Jolley, Hansen and Trost. Originally Sourced: https://vimeo.com/35882401

A note on the images: Firstly, I would like to thank artist Reynold Reynolds and Art Studio Reynolds not only for permission to use images from “Burn” (2002) but for generously providing me with the two still I have used in the text.

Emails were sent to the contact email from the Patrick Jolley Estate website and to Inger Lise Hansen asking permission to use stills from “Here after” (2004). But Idid not get any reply. (I could not find contact information forRebecca Trost)

I am using the images in good faith, in that I have not received any objections, so I am presuming it is acceptable to proceed. The stills used were taken from the film editor Bobby Good’s Vimeo page, he worked with Patrick Jolley on a number of projects, he has since moved the video to his own webpage where it is still free to view:http://www.bobbygood.de/portfolio/patrick-jolley-hereafter

The Patrick Jolley Estate has videos embedded in their website for the public to view. If I am contacted by the Patrick Jolley Estate, Rebecca Trost or Inger LiseHansen to say they do not want the images used they will be immediately removed.

Bibliography

- Abrams, L. Oral history theory (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge 2016

- Adorno, T. Minima moralia : Reflections from damaged life (Radical thinkers). London: Verso. (2005)

- Arendt, Hannah, and Canovan, Margaret. The Human Condition. 2.nd ed. Chicago, Ill.: U of Chicago, 1998.

- Bachelard, Gaston The Poetics of Space Beacon Press, Boston, 1994. Originally published in French under the title La poetique de l’espace by Presses Universitaires de France, 1958

- Baer, U. Spectral evidence: The photography of trauma. Cambridge, Massachusetts MIT Press. 2002.

- BBC News Website, report on the Grenfell Tower Fire. http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-40272168. Date Published: 19/07/2017 Date accessed: 15/04/2018

- Bloom M.D,Sandra L. Reenactment. 2010. Sourced: http://sanctuaryweb.com/Portals/0/2010%20PDFs%20NEW/2010%20Bloom%20Reenactment.pdf Date accessed: 29/11/2017

- Boothby R. “Now You See It …”: The Dynamics of Presence and Absence in Psychoanalysis. p.397-430 In: Babich B.E. (eds) From Phenomenology to Thought, Errancy, and Desire.: Essays in honor of William J. Richardson, S.J. Phaenomenologica (Collection Fondée par H.L. van Breda et Publiée Sous le Patronage des Centres d’Archives-Husserl), vol 133. Springer, Dordrecht. 1995

- Boucher, Geoff. Adorno Reframed: Interpreting Key Thinkers for the Arts. Contemporary Thinkers Reframed Series. London: I.B. Tauris. Print. 2013

- Briganti, Chiara & Mezei, Kathy editors The Domestic Space Reader. Toronto, Buffalo, London, University of Toronto Press,2012

- Buse, P., & Stott, A. Ghosts: Deconstruction, psychoanalysis, history. Basingstoke: Macmillan. 1998

- Byrne, Nicola & McDonald, Henry. More cheers than tears as Ballymun is destroyed Published: 11/07/2004 Date accessed: 20/02/2018 https://www.theguardian.com/society/2004/jul/11/communities.regeneration

- Castle, Terry. The female thermometer: Eighteenth-Century culture and the invention of the uncanny (Ideologies of desire). New York: Oxford Univ. Press. 1995

- Crow, C. editor. A Companion to American Gothic (Blackwell companions to literature and culture; 85). Chichester: Wiley Blackwell. 2014

- Farago, Jason “Doris Salcedo review – an artist in mourning for the disappeared” https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/jul/10/doris-salcedo-review-artist-in-mourning 2015. Date accessed: 10/04/2017

- Focus Ireland Charity. Report and regularly updated figures: Why are so many people becoming homeless? https://www.focusireland.ie/resource-hub/about-homelessness/ Date accessed: 20/02/2018 & 12/05/2018

- Foster, Dawn Right to Buy: a history of Margaret Thatcher’s controversial policy https://www.theguardian.com/housing-network/2015/dec/07/housing-right-to-buy-margaret-thatcher-data Published: 07/12/2015. Date accessed: 06/05/2018

- Foster, Hal. Death in America article published in October Vol.75, p. 36-39 Winter 1996 Cambridge, Massachusetts, MIT Press. 1996

- Freud, Sigmund The Uncanny (first published 1919) Penguin Books Ltd., London. 2003. First published in Imago, Bd. V., 1919; reprinted in Sammlung, Fünfte Folge.

- Gelder, Ken editor The Horror Reader Routledge Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Informa PLC, London 2005

- Good, Bobby http://www.bobbygood.de/portfolio/patrick-jolley-hereafter Date accessed: 12/05/2018

- Goodwin, Sarah Webster, and Elisabeth Bronfen. Death and Representation. Baltimore: John Hopkins U. Parallax. 1993

- Gordon, Avery “‘Who’s there?’: some answers to questions about ghostly matters” (2007). Talk presented at United Nations Plaza (Berlin) for Seminar 6: “who’s there?—an interrogation in the dark” organized by Natascha Sadr Haghighian, Ines Schaber, Anselm Franke (22–26 October 2007). Available here: http://www.averygordon.net/writing-haunting/whos-there/ .Date accessed: 01/08/2017

- Gray, R. Online notes from University of Washington for German Lit., English Lit. and Literary Composition courses. http://courses.washington.edu/freudlit/Uncanny.Notes.html Date accessed: 21/10/2016

- Hansen Inger Lise’s website http://www.ingerlisehansen.com/text.html Date accessed: 01/07/201

- Hogle, J. editor. The Cambridge companion to the modern gothic (Cambridge companions to literature) 2014

- Houses of the Oireachtas. (The Irish Parliament and seat of government) official website. Transcript of : Adjournment Debate. – Ballymun (Dublin) Living Conditions Dáil Éireann debate – Tuesday, 20 Feb 1990 http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/debates%20authoring/debateswebpack.nsf/takes/dail1990022000027?opendocument Beta of new website:https://beta.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1990-02-20/26/?highlight%5B0%5D=february&highlight%5B1%5D=1990&highlight%5B2%5D=ballymun&highlight%5B3%5D=ballymun&highlight%5B4%5D=ballymun&highlight%5B5%5D=ballymunTranscript of: Committee on Finance.- Vote 26 — Local Government (Resumed)DáilÉireann debate – Thursday, 7 Dec 1967 http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/Debates%20Authoring/DebatesWebPack.nsf/takes/dail1967120700008 Beta of the new website: https://beta.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1967-12-07/7/?highlight%5B0%5D=committee&highlight%5B1%5D=finance&highlight%5B2%5D=vote&highlight%5B3%5D=26&highlight%5B4%5D=local&highlight%5B5%5D=government&highlight%5B6%5D=resumed Date accessed: 20/02/2018

- Humphries, Jane from Subversion to Celebration: The Emergence of a Domestic Avant in Contemporary Irish Art M.Phil. Thesis Irish Art History, University of Dublin, Trinity College, 2006

- Kearns, David Dublin Fire Tragedy: ‘There are 14 people now without homes who need help’ says Southside Traveller group https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/dublin-fire-tragedy-there-are-14-people-now-without-homes-who-need-help-says-southside-traveller-group-31600474.html Published: 11/10/2015 Date accessed: 15/04/2018

- Kelly, Olivia Council tenants may get 60% discount to buy houses https://www.irishtimes.com/news/social-affairs/council-tenants-may-get-60-discount-to-buy-houses-1.2625578 Published:27/04/2016. Date accessed: 06/05/2018

- Kristeva, Julia Translated by Roudiez, Leon S. Strangers to ourselves Columbia University Press, 1991. First published by Librairie Artheme Fayard, 1988

- Kristeva, J. Powers of horror: An essay on abjection (European perspectives). New York: Columbia U. P. 1982

- Jentsch, Ernst On the Psychology of the Uncanny PDF sourced from http://blog.worldswithoutend.com/2011/09/automata-101-gothic-romance-and-the-uncanny/#.WGK6frF0fdQ in an article by Rhonda Knight. Originally Zur Psychologie des Unheimlichen was published in the Psychiatrisch-Neurologische Wochenschrift 8.22: pp. 195–8 (25 Aug. 1906) and 8.23: pp. 203–5 (1 Sept. 1906). Date accessed: 09/10/2016

- Loughran, Hilda Dr. & McCann, Mary Ellen Dr. “Ballymun Community Case Study: Experiences And Perceptions Of Problem Drug Use” from 2006 available from Irish National Advisory Committee on Drugs School of Applied Social Science , University College Dublin (2006) http://www.drugs.ie/resourcesfiles/research/2006/NACD_Ballymun_Case_Study.pdf Date accessed: 15/04/2018

- McDevitt, Niall Article: No Poetry after Adorno on The International Times website: http://internationaltimes.it/no-poetry-after-adorno/ Published September 2012. Date accessed 05/10/2017

- McGuire, Kristi. The University of Chicago, Theories of Media, Keywords Glossary: Object Petit A. http://csmt.uchicago.edu/glossary2004/objectpetita.htm Date accessed 30/09/2017

- “Maddalo” Blog post Death/Women/Power: The Sublime and Beautiful in Burke http://maddalo.blogspot.se/2015/02/deathwomenpower-sublime-and-beautiful.html 2015. Date accessed: 02/03/2017

- Masschelein, Anneleen A Homeless Concept Shapes of the Uncanny in Twentieth-Century Theory and Culture Published in “Image & Narrative” Online Magazine of the Visual Narrative, Issue 5. The Uncanny –Guest editor: Anneleen Masschelein. ISSN 1780-678X, January 2003, Article available here:http://www.imageandnarrative.be/inarchive/uncanny/anneleenmasschelein.htm Issue available here: http://www.imageandnarrative.be/inarchive/uncanny/uncanny.htm Date accessed 14/09/2017

- Masschelein, A. The unconcept : The Freudian uncanny in late-twentieth-century theory (Suny series, Insinuations: philosophy, psychoanalysis, literature). Albany, NY: SUNY Press. 2011

- Mercyhotsprings. Video of Inger Lise Hansen’s film “Hus” (1997) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H2V4K2BU2mo Published: 15/11/2011 Date Accessed: 10/03/2018

- Merewether, Charles. “To Bear Witness”, in: Doris Salcedo. Edited by: Tim Yohn. New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art 1998

- Middleton, Nicholas Photography & The Uncanny http://www.nicholasmiddleton.co.uk/thesis/thesis3.html 2005. Date accessed: 05/12/2016

- Neil, Ken. Repeat: Entity and ground. Visual arts practice as critical differentiation Chapter four pp.60-72 In Thinking Through Art: Reflections on Art as Research edited by Katy Macleod & Lin Holdridge. London, Routledge Press. 2009

- Notthoff, Anna-Verena Barbarism: Notes on the Thought of Theodor W. Adorno published in” Critical Legal Thinking – Law and the political” (Oct. 2014) Access here :http://criticallegalthinking.com/2014/10/15/barbarism-notes-thought-theodor-w-adorno/ Date accessed 05/10/2017

- Perkins Gilman, Charlotte The Yellow Wallpaper (1st published 1892) London, Virago Press. 2005 edition.

- Patrick Jolley Estate. Archive of Jolley’s work includes essays and reviews of his art and practice. http://patrickjolleyestate.com Date accessed: 20/01/2018

- Power, Jack Over ¢4m for Traveller housing left unspent https://www.irishtimes.com/news/social-affairs/over-4m-for-traveller-housing-left-unspent-1.3371661 Published: 29/01/2018 Date accessed: 15/04/2018

- Punter, David editor A New Companion of the Gothic Wiley Blackwell Ltd., Sussex, U.K 2015

- Reynolds, Reynold http://artstudioreynolds.com Date accessed: 10/03/2018 Art Studio Reynolds Vimeo page: Drowning room(2000)https://vimeo.com/34463913; Burn2002 https://vimeo.com/20706577, “Sugar” (2005) https://vimeo.com/19667993Date accessed: 09/11/2016

- Salcedo, D., & Basualdo, C. Doris Salcedo (Contemporary artists). London: Phaidon. 2000

- Searson, Sarah & Shaffrey, Cliodhna editors site manager, Brady, Jenny http://www.publicart.ie/main/directory/directory/view/hereafter/4d5984e34400862fa22d0e2d05898a96/ The site is managed by the Arts Council Ireland. Date accessed: 18/12/2016

- Todorov, T. The fantastic: A structural approach to a literary genre (Cornell paperbacks). Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press. (1975)

- Trigg, D. The memory of place : A phenomenology of the uncanny (Series in Continental thought ; 41). Athens: Ohio University Press. (2012).

- Van der Kolk MD, Bessel A. Article: The Compulsion to Repeat the Trauma, Re-enactment, Revictimiztaion and Masochism in Psychiatric Clinics of North America, Volume 12, Number 2, Pages 389-411, June 1989. Sourced from: http://www.cirp.org/library/psych/vanderkolk/ Date accessed: 29/11/2017

- United Nations website. Universal Declaration of Human Rights http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ Date accessed: 05/05/2018

- Walker, Gregory A. editor American Horrors University of Illinois Press,1987

- Withy, Katherine Heidegger on Being Uncanny Cambridge Massachusetts & London, Harvard University Press. 2015

- White, Jonathon. Article: Precarious work and contemporary capitalism https://mronline.org/2018/03/30/precarious-work-and-contemporary-capitalism/ Published: 30/03/2018 and notes on the article: https://tradeunionfutures.wordpress.com/2018/03/27/precarious-work-and-contemporary-capitalism/ Published: 27/03/2018 Date Accessed: 03/05/2018

- Yansori, Ali The Concept of Trauma in Lacanian Psychoanalysis http://psychoanalyzadnes.cz/2018/02/19/the-concept-of-trauma-in-lacanian-psychoanalysis/ Published: 19/02/2018 Date accessed: 15/04/2018

- Žižek, Slavoj. Welcome to the desert of the real!: Five essays on 11 September and related dates. London; New York: Verso. 2002

Endnotes

- It would be remiss of me not to mention some of the many other recent and contemporary artists whose work deals with the domestic and the uncanny, as examples of the context Jolley’s work can be placed in e.g. Gregor Schneider, Robert Gober, Louise Bourgeois, Jonas Dahlberg, Ron Mueck, Cindy Sherman, Sarah Lucas, Gregory Crewdson, Mike Kelly, Mona Hatoum, Doris Salcedo, Shadi Ghadiran, Shona Illingworth, Erwin Wurm, Lori Nix, Mark Manders, Sonja Braas.

- Here after (2004) http://www.bobbygood.de/portfolio/patrick-jolley-hereafter

- By this I mean that our ideas of the domestic space are both constructed through personal experience and culturally given notions.

- Freud, Sigmund The Uncanny (first published 1919) Penguin Books Ltd., London. 2003. First published in Imago, Bd. V., 1919; reprinted in Sammlung, Fünfte Folge. His writing on the uncanny was somewhat inspired by Ernst Jentsch essay- “On the Psychology of the Uncanny” (1906) and a number of other works e.g. German philosopher Friedrich Schelling, Otto Rank’s where he associates the uncanny with the spiritual, or feeling a closeness to the divine. ‘The Double’ of 1914 (which was not translated to English. “The double a psychoanalytical study 1925” was translated to English and published in 1971)

- For interesting thoughts on the sublime see: Blog post “Death/Women/Power: The Sublime and Beautiful in Burke” http://maddalo.blogspot.se/2015/02/deathwomenpower-sublime-and-beautiful.html 2015. “Terror Sublime” is discussed in paragraph 3.

- Freud’s theory around the compulsion to repeat, as related to anxiety and trauma, have been explored further by Lacan and his idea of “jouissance” (beyond the pleasure principle) where there is a pleasure and pain in this compulsive repetition [in the way that people cope with trauma]) which he also connects to anxiety and to the “objet petit a” (the unattainable object of desire). “object petit a” as defined by Kristi McGurie http://csmt.uchicago.edu/glossary2004/objectpetita.htm The University of Chicago, Theories of Media.

- Terry Castle has written on the origins of the uncanny in her book “The Female Thermometer, 18th century culture and the invention of the uncanny” tracing its origins to the Enlightenment.

- Originally in Daniel Sanders’ 1860 dictionary Worterbuch (which Freud quotes in his essay The Uncanny [1919] [Freud,2003, p.134]).

- Louis Vax “Que sais-je” pocket series on “L’art et la littérature fantastique” Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. (1960). Louis Vax’s phenomenological approach to the uncanny is somewhat echoed in Tzvetan Todorov’s work “The Fantastic: A structural approach to a Literary Genre” (1975) where he defines the fantastic or the uncanny as an experience we label after the fact. It is named after the occurrence of our intellectual hesitation/uncertainty a result of encountering something which we find undefinable or estranged from categorization.

- It may also near Edmund Burke’s ideas of the “terror sublime” as mentioned earlier in the text

- By which I mean it doesn’t have to be unattractive /horrific /repulsive in appearance to meet the criteria of the uncanny.

- Julia Kristeva’s renowned works Powers of horror: An essay on abjection (1982) and Strangers to ourselves (1988) (English translation 1991).The philosopher Heidegger’s theories around the uncanny differ somewhat, he considered that as humans we can experience the uncanny due to the strangeness of being aware of existence, there is an uncanniness to ‘being’. “Dread reveals no-thing.” Heidegger in What is Metaphysics Translation by Miles Roth p.44. Source: http://wagner.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/psychology/files/2013/01/Heidegger-What-Is-Metaphysics-Translation-GROTH.pdf Also see Katherine Withy’s Heidegger on Being Uncanny (2015) section “Uncanniness” p.92Mark Fisher in his 2016 work “The weird and the eerie” considers “Freud’s ultimate settling of the enigma of the unheimlich – his claim that it can be reduced to castration anxiety – is as disappointing as any mediocre genre detective’s rote solution to a mystery” (p.9, par.3). Mark Fisher attempts to untangle the weird and eerie from the uncanny, he places the weird with the strange and changed and the eerie in connection with absence and presence. I place these two firmly in relation with the uncanny, I believe the uncanny has room in encompass the weird and the eerie esp. in relation to absence and presence which can be tied to Lacan’s seminars on anxiety at the Hospital Sainte-Anne in 1962- 1963 where he discussed the uncanny in association with “lack” “object-a”, “desire” “extimacy” and of course anxiety, these lectures are referred to in The unconcept : The Freudian uncanny in late-twentieth-century (2011) (p.52-p.59)

- Drowning room (2000) https://vimeo.com/34463913; Burn 2002 https://vimeo.com/20706577, http://artstudioreynolds.com/burn/

- Here after (2004) http://www.bobbygood.de/portfolio/patrick-jolley-hereafter

- “Sugar” (2005) https://vimeo.com/19667993 “Art Studio Reynolds” Vimeo page.

- http://www.ingerlisehansen.com/filmpages/hus.html , https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H2V4K2BU2mo Jolley continued to be interested in using time/pacing to create tension in his film pieces. For example “Sitting Room” from 2012. http://patrickjolleyestate.com/portfolio/sitting-room/ and the influence of Samuel Beckett and other existentialist playwrights seems plausible, perhaps more apparent in his work where people play a role.

- A subject tackled by Anthony Vidler in his book “The Architectural Uncanny” (1992).

- On Psychology of the Uncanny (1906) Ernst Jentsch referring to imitation (P.8); The Uncanny (1919) Sigmund Freud referring to the haunted house (P.148)

- Please note The Oireachtas website is being updated. The new site is only available in beta. But I will put both versions in the bibliography. A debate in the Irish Dail by ministers, on efforts to address issues and aid improvements in Ballymun from 1990 http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/debates%20authoring/debateswebpack.nsf/takes/dail1990022000027?opendocument Debate from 1967 two years after the Ballymun Housing project was built addressing the mistakes and lack of planning involved http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/Debates%20Authoring/DebatesWebPack.nsf/takes/dail1967120700008 Article in the Guardian newspaper reporting on the tower blocks demolition from June 2004 https://www.theguardian.com/society/2004/jul/11/communities.regenerationAn interesting report from the School of Applied Social Science , University College Dublin “Ballymun Community Case Study: Experiences And Perceptions Of Problem Drug Use” from 2006 available from Irish National Advisory Committee on Drugs (2006) by Dr Hilda Loughran and Dr Mary Ellen McCannhttp://www.drugs.ie/resourcesfiles/research/2006/NACD_Ballymun_Case_Study.pdf

- A point played out in the economic crash of 2007 where people lost their homes, the current squeezed rental market and the ongoing homelessness crisis resulting from this, in March 2018 the officially figures were: 9,681homeless people, 3,646 of which were children. The most recent figures (from 2016) showed 61,600 households qualified as being in need for social housing https://www.focusireland.ie/resource-hub/about-homelessness/

- p.250 The Gothic Film by Heidie Kaye published in A new companion to The Gothic edited by David Punter 2015 edition Publisher: Wiley Blackwell Ltd., Sussex, U.K (p.239-p.251)

- In The Trauma of infancy in Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby. Virginia Wright Wexman writes ‘ I love the clichés,’” … Polanski has said… Practically every film I make starts with one. I just try to update them, give them an acceptable shape The way he updates clichés…implicitly forces us to confront the ways in which we use the institutions of popular genres to express and disguise the structures of power underlying social interactions (p.31) Published in American Horrors University of Illinois Press,1987, editor Gregory A. Walker (p30-43)

- More on Jacques Lacan’s The Real : http://csmt.uchicago.edu/glossary2004/symbolicrealimaginary.htm The Real with popular culture examples http://psychoanalyzadnes.cz/2018/02/19/the-concept-of-trauma-in-lacanian-psychoanalysis/

- the doppelganger, the unintentional return, but also the compulsion to repeat, the return of the repressed, and re-enactment as it relates to trauma. Also see: Freud’s essay “The Uncanny” (1919) p142, p144-145,M.D,Sandra L. Bloom’s essay Reenactment. 2010. http://sanctuaryweb.com/Portals/0/2010%20PDFs%20NEW/2010%20Bloom%20Reenactment.pdf

- Be that the habitual of the banal everyday routines of the domestic space, or the social norms and mores we have become habituated to, so much so that we tend to overlook or forget to question them.

- or attempt to repress it on a societal level.

- Jean Baudrillard Symbolic exchange and death 1993 as discussed in the essay ‘The Gothic Ghost of the Counterfeit and the process of Abjection by Jerrold E. Hogle published in A new companion to The Gothic edited by David Punter 2015 edition Publisher: Wiley Blackwell ltd., Sussex, U.K p.496-509Point as referred to earlier in this essay, about the persistence of gothic tales. That they may seem to be destined to be continually reborn to suit the fears and desires of each new period p.250 The Gothic Film by Heidie Kaye published in A new companion to The Gothic edited by David Punter 2015 edition Publisher: Wiley Blackwell ltd., Sussex, U.K (p.239-p.251)

- Ireland is not alone in this, in having incompetent and/ or uncaring governance, the widening economic gap can be seen in many countries, and as the West and Europe are forced to face the reality and side effects of wars in the middle east and their colonial pasts- in the ongoing refuge crisis- the types of homes these fellow world citizens can hope for must also be considered.Detention centres and group housing that quickly turn from the temporary to the long term, echo back to the ghettos, tenements and poorly built tower blocks that we would like to think we have moved on from. The Home can be seen to be addressed in article twenty two (which refers to social security) and article twenty five (in regard to a basic standard of living including food and shelter) of the UN’s list of Human Rights. http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/The West has always talked to itself of the improvements it has enjoyed- the increased quality of life, health and life expectancy. But for us, for the Europeans, for people from North America, for the West. From our colonial past- first occurring with our own neighbours and then across the far reaches of the globe- we have robbed resources and enslaved people, we must recognise much of these improvements have been on the back of other nations suffering. The citizens of other countries have often not seen any of the benefits of our great surge forever forward into the Hegelian future. Today much of our consumer products are made in conditions we will no longer tolerate for ourselves, but we will ignore if it means we get a cheap new t-shirt and the latest i-phone for a little less.It seems with all our grand ideals and rhetoric we can also ignore our own citizens, the poor and the underclasses, the abject of society and the refugees of recent years, which is clear evidence that our utopia does not exist; that our privilege is not just a matter of luck but a direct result of the neglect and disenfranchisement of others. Works like “Here after” makes us face the effect of this neglect and to consider the position of people in our own societies. But also, to reflect on the wider socio political issues we face when it comes to the right to a home with safety and shelter and whether or not these basic human rights, that our countries have signed up to, are even being attempted to be met…if we as a society or/and as individuals even care at all.

- The Irish Times newspaper: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/social-affairs/over-4m-for-traveller-housing-left-unspent-1.3371661 The Irish Independent newspaper: https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/dublin-fire-tragedy-there-are-14-people-now-without-homes-who-need-help-says-southside-traveller-group-31600474.html

- The Grenfell Tower tragedy in London in 2017. BBC news report on the Grenfell Tower fire: http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-40272168

- But they have followed on a tradition, in the 1970s under Charles Haughey’s leadership people in social housing were giving the opportunity to buy their houses, paying directly to their local council as opposed to a bank. A wonderful way to help people own a home that would otherwise be prohibited to them. But the money was not reinvested in social housing. There was already a lack of public housing but this action left the country with a terrible deficit of badly needed homes and no government since has been interested in addressing it. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/social-affairs/council-tenants-may-get-60-discount-to-buy-houses-1.2625578 by Olivia Kelly ( Thatcher’s Conservative government in the UK in the 1980s also promoted a “Right to buy” scheme https://www.theguardian.com/housing-network/2015/dec/07/housing-right-to-buy-margaret-thatcher-data by Dawn Foster)

- The 3,267 children homeless, as mentioned earlier in this text, often sleep in B&Bs or are moved from shelter to shelter. (Figures from March 2018. Source as quoted in endnote 20. https://www.focusireland.ie/resource-hub/about-homelessness/ )

- Many home owners have been left in negative equity. There is a lack of long term security when it comes to employment which effects the people’s ability to attain and retain a home, seen also in the demand for a more mobile work force where companies want their employees to transfer where and when they are needed, a notable move to agency work as opposed to direct employment and the existence of zero hour contracts. There is an interesting essay which addresses some of these points “Precarious work and contemporary capitalism” by Jonathon White in the “Monthly Review Foundation- MR Online” (the particular focus is on the situation in Britain) https://mronline.org/2018/03/30/precarious-work-and-contemporary-capitalism/ or https://tradeunionfutures.wordpress.com/2018/03/27/precarious-work-and-contemporary-capitalism/