How to use photography to get closer to nature: A field guide

I am sitting in my car alone, driving. It’s winter, it’s snowing, and it’s pitch dark. I’m tired, there have been many hours on the road. Some time ago I took a turn off the highway, into the smaller inland roads where the traffic gets more and more sparse the further away from the coast you get. But I still have many hours left to go. I just passed a village, where I was centimetres from crashing into an oncoming snowplough. But I’m safe now, as long as I’m careful.

The forest is dense and dark on both sides of the road. The only light is from the cars’ headlights. I am on my way to the area where my grandmother grew up, in the inland of Västerbotten, close to the Norwegian border. I have the car fully packed with most of my cameras and a load of film that will last me for weeks. It’s January, and the thermometer shows minus 25 degrees Celsius.

Suddenly, just after a turn, a flock of reindeer are standing in the middle of the road. I hit the brakes, the car slides onto the ice and is impossible to control. I start to panic, but the tyres finally grip the road and the car stops just a meter away from the reindeer, who are unmoved. I get out of the car and look at them. The only sound comes from the car fighting the cold. Everywhere else there is nothing. Just me and the reindeer. Just me and nature.

The word ‘nature’ is said to be one of most difficult words to define. It stands for the wild – the forests, the seas, the mountains and the animals. But it is also a representation of human history, a reflection of our idea of ourselves, our society and the world outside our society.

In his essay Ideas of Nature (1980), the British academic and critic Raymond Williams points out two basic meanings of the word: according to the first definition, nature stands for the ‘true’ essence of reality. In the second definition, nature is the piece of the world that has not been formed by humans. Together, these definitions give the word quite a wide meaning. But one thing is certain, nature can’t be understood without relating it to ourselves.

I grew up in a suburb of Stockholm. My grandmother, on the other hand, was born in a small village in the middle of the forest, in the sparsely populated inland of Västerbotten in the north of Sweden. She moved to Stockholm in the 1940s during the war and lived the rest of her life there. My grandmother was a restless person who was unfortunately never at peace with herself during her life. When I was a child, she often told me stories about her home village and her own childhood. Her parents were farmers, like most of the people in the area at the time, and the households were mainly self-sufficient. It was a hard life, and the line between surviving and starvation could, in bad years, be slim. Despite this, she always talked about her home village with warmth. These were fascinating stories for me as a child, a huge contrast from where I grew up in Stockholm. Through her stories, Västerbotten and its nature became a place loaded with magic, and it eventually grew into a symbol for everything that I felt was missing in my life.

My interest in Västerbotten increased with the passing of my grandmother in 2019. I found myself thinking more and more about nature, and eventually felt that I had no other choice than to work with the subject. I wanted to feel a connection to the land of my ancestors, a place I only knew through my grandmother’s stories. I wanted to understand my roots and I wanted to get closer to nature.

As a photographer, an interest in the Nordic landscape has for a long time been present in my work. But it was not until lately that nature really started to play a bigger and more important role. For the past ten years, I have used photography to create my own emotional narrative and history. A truth, maybe, that somehow makes more sense to me. The use of photography has been my way of connecting and creating a feeling that I belong somewhere.

I have many times used photography to create a relationship to people and places that has for me been unknown, but I had never before used it to create a bond to nature itself. Since the aim of this work was different in comparison to projects I’ve previously worked with, I quickly realised that I could not implement my normal way of working. I started researching photographers and artists who had been working with photography in relation to nature to get some insight into their processes. However, quite soon I realised that I had to be in nature myself to figure out what it meant to me. So I decided to go to Västerbotten and photograph.

I packed my car with almost all of my cameras and film. Large format, medium format and different kinds of black and white and colour film. I was not sure what the process would be, but I felt an urge to experiment and leave room for chance. I did feel insecure in stepping back from the controlled way of making photographs that I knew by heart. Nonetheless, I was excited when I was heading North.

It was a long drive from Stockholm, and it became even longer since I decided to take the small inland roads. The long journey gave me a lot of time to think, and the closer I got to my destination, the more hesitant I became about my abilities. Could I step away from the controlled process of making photographs? How much room should I leave for chance? Just using different films and a 4×5 field camera was a huge step out of my comfort zone. What if the results turned out bad – or worse, unusable? I was nervous about coming across as a bad artist and photographer, someone who did not know what he was doing. This realisation made me anxious, but also alert and determined.

Experimenting with photography with the aim of investigating nature has been attemped by numerous other photographers before me. One photographer whose process I studied in the research for this task was the Swedish writer August Strindberg (1849 – 1912). He is one of Sweden’s most prominent authors, but what is less known is that he was also a painter and an experimental photographer. In the winter and spring of 1894, he conducted a series of experimental photographs with the aim to make a more “true and objective” representation of nature.

Strindberg was influenced by the rapid developments in science at the time, and his aims with his photographic experiments were, unlike mine, scientific rather than artistic. When I read his essay Om ljusverkan vid fotografering (‘About the influence of light during photographic image making’), released in 1897, this becomes clear. In the text he describes his photographic experiments. He started by removing the lens from the camera, instead making a hole with a needle for the light to come in – today, we would call this a pinhole camera. Then, he compared the resulting photographs with others on the same subject conducted with a normal photographic lens. Viewing the results, he argued that photographing without a lens makes the light pass more freely through the camera, creating a more ‘representative’ image of reality.

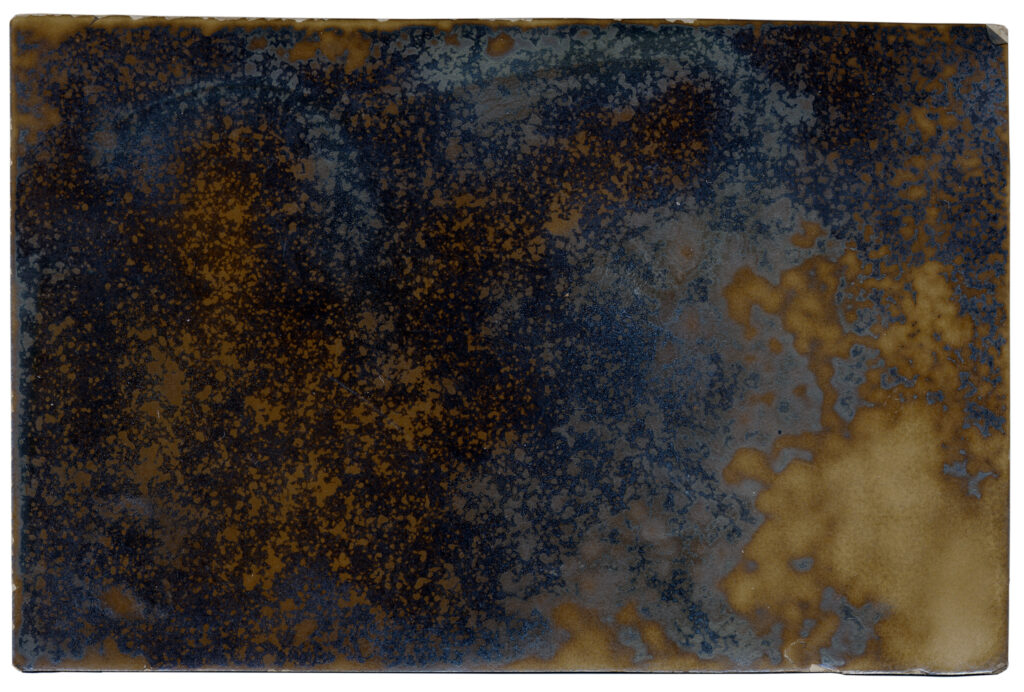

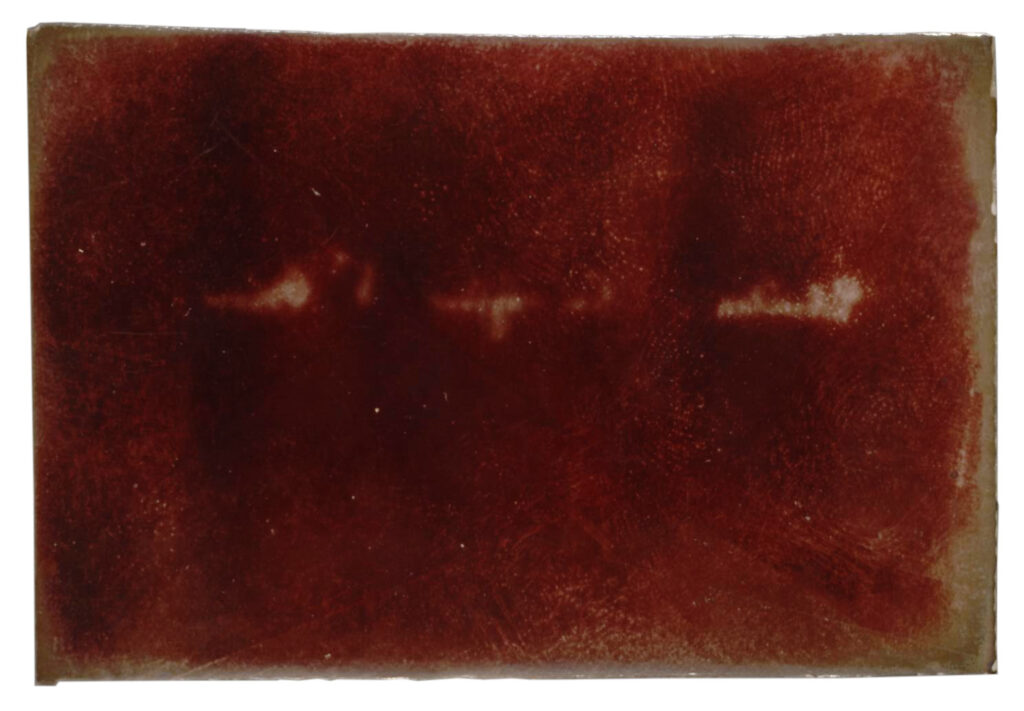

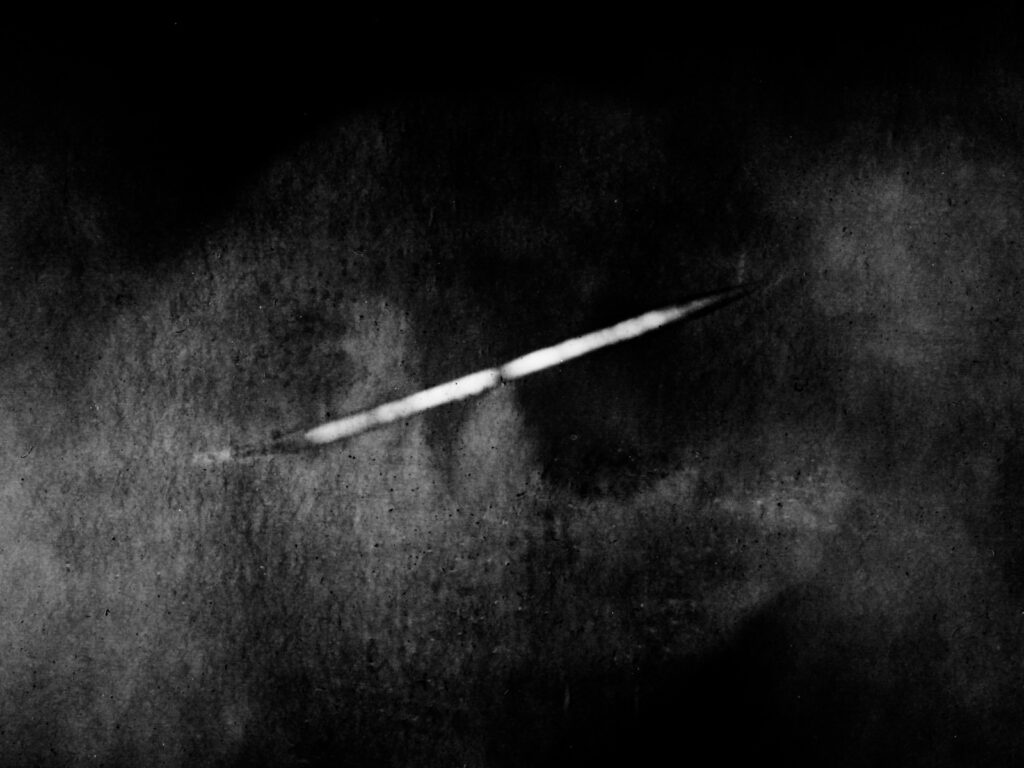

His next step was to remove the camera completely from the photographic process. Instead, he put a photographic bromo silver plate placed in developer on the ground during the night or the day. His aim was to capture the stars, the moon and the sun straight on the plate without any interference of a camera or a photographic lens. He called his newly invented technique “Celestography” after the French word for sky: céleste.

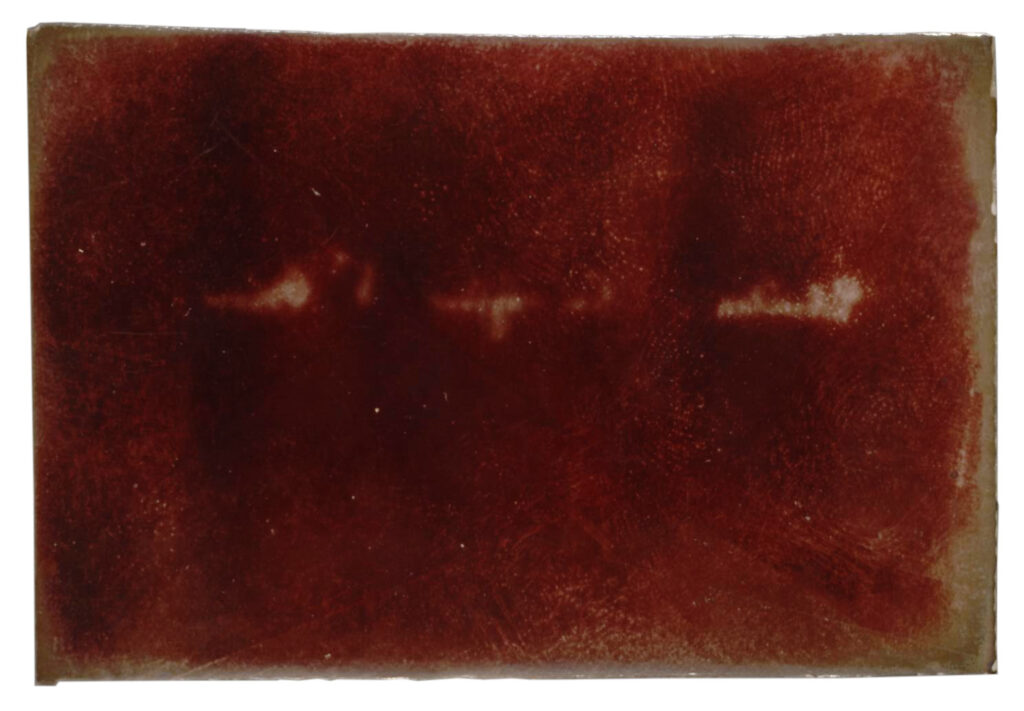

When Strindberg ‘photographed’ the sunset with this technique, the result was an image that he described as “covered in flames”. With a photograph of the starry sky, the plate was covered with “small white dots”.

He thought that this outcome proved his thesis, and therefore he had invented a new way of making photographs. He sent his celestographs to the French Astronomic Society for evaluation. The society, however, was not interested in his experiments. They probably knew what we know today: the plates were instantly destroyed by the light outdoors, and the traces on them were simply a result of a chemical reaction. The small white dots Strindberg interpreted as stars were actually no more than specks of dust. But Strindberg was a stubborn man and was nevertheless certain that he’d invented a new way of making photographs. He ends his essay from 1897 with the quote:

“Physics and chemistry have not yet solved the world’s problems: that the laws of nature are simplifications, dictated by simple people and not by nature, and that the universe still hides its secrets from us.” [i]

Strindberg saw the altering of the photographic process as necessary to create new knowledge about the world around us. Despite his scientific approach, I realised that he was onto something. I too felt an urge to step away from the camera’s reality-recording capacity and alter the photographic process to visualise something else, other than what I could see with my eyes.

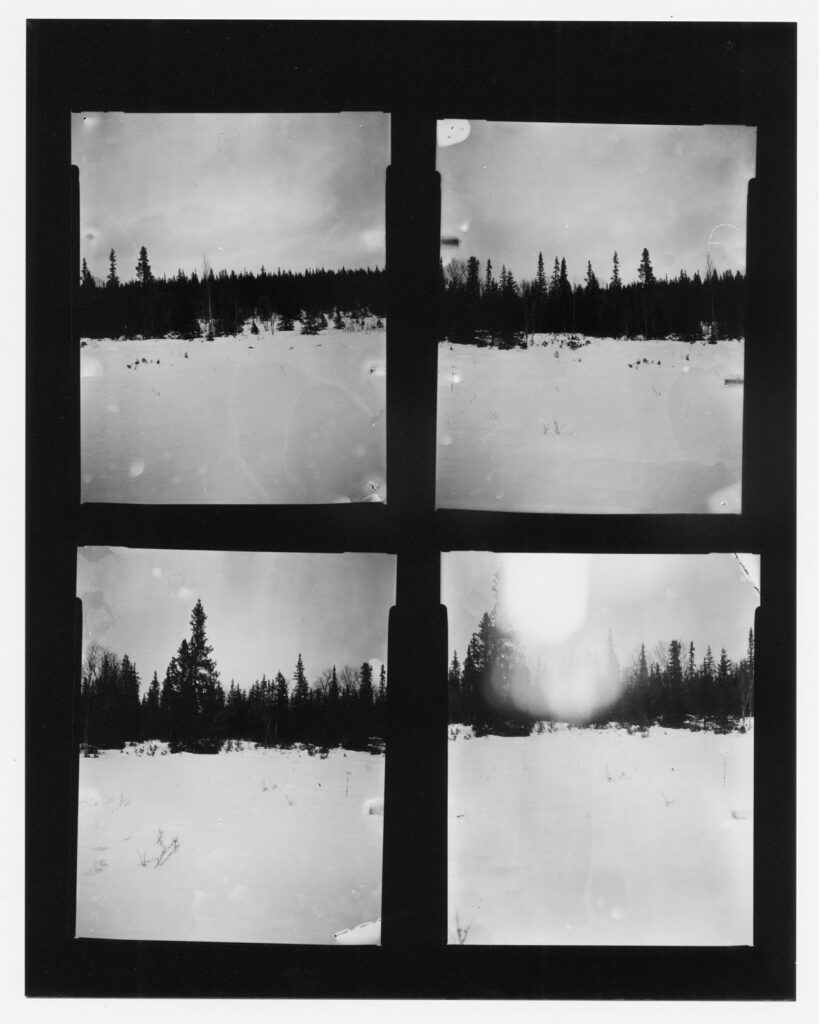

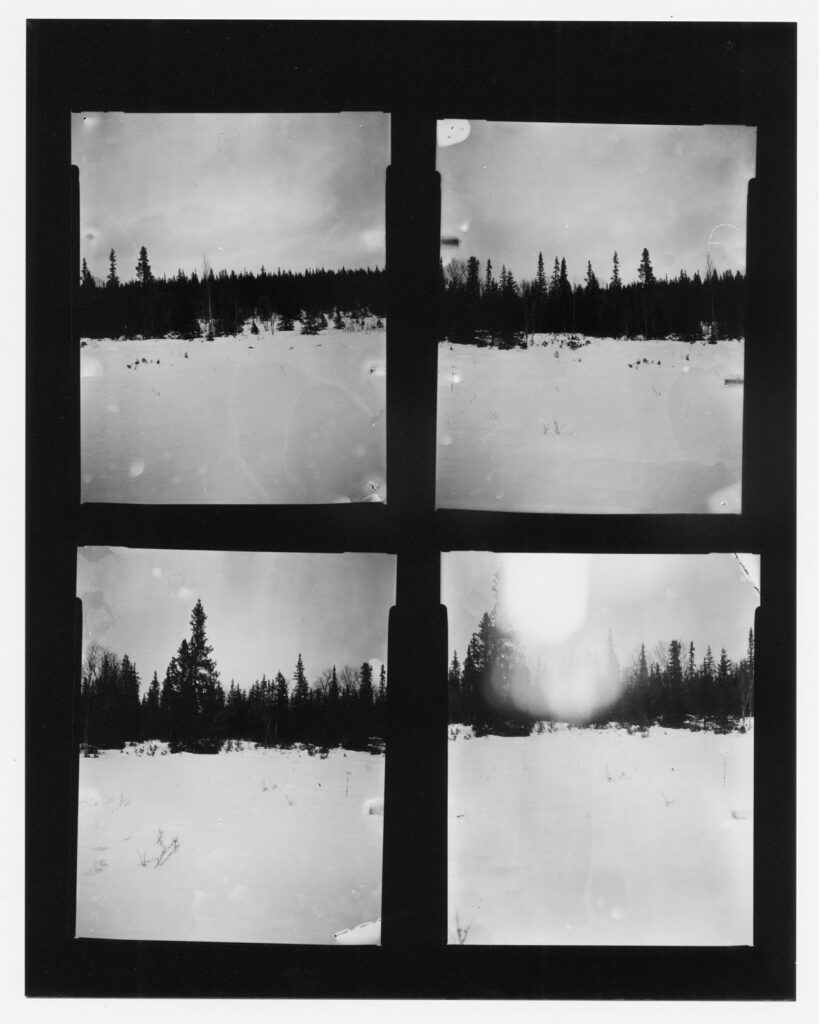

After my first visit to Västerbotten, I went through my contact sheets to view the results. When I map out a new project, I usually take a lot of pictures, aiming high and low. Most of the pictures are, in this stage, unusable, but it is in this process where I find the leads. In the contact sheets I found some images where I felt the aiming was right. There were some light leaks and accidental double exposures that came out of my unfamiliarity with a 4×5 field camera, as well as some over and under exposures. These accidents somehow added to the feeling I had when taking the photograph. I realised that the photographs were not depicting what I saw, but rather they depicted what I sensed when being in nature.

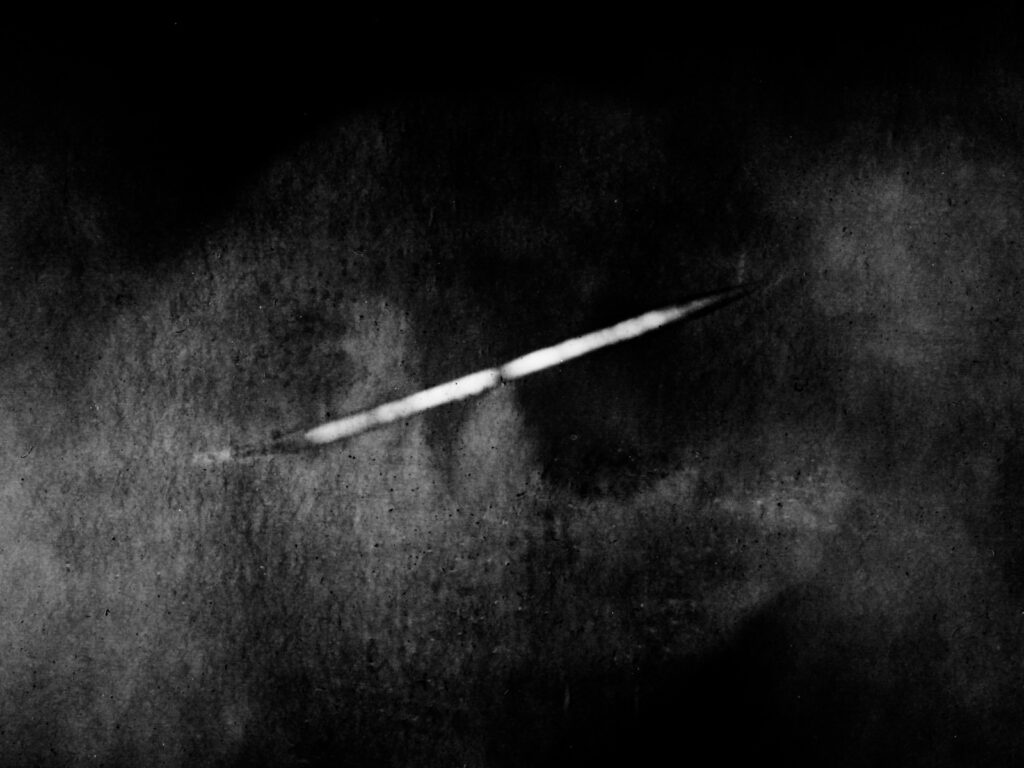

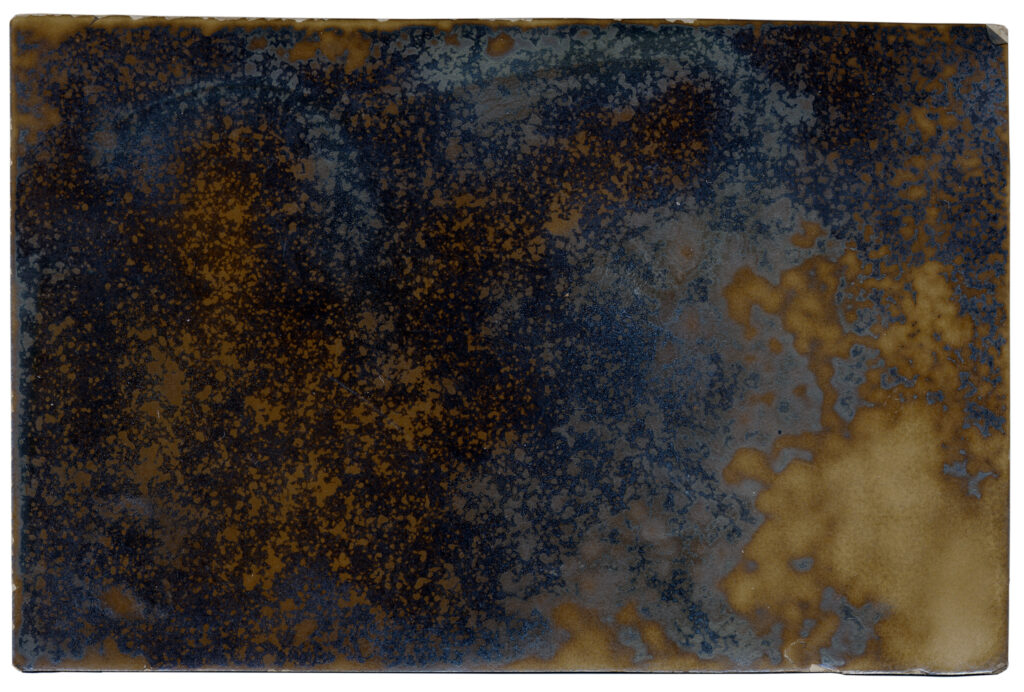

On my next visit to Västerbotten, I started to build pinhole cameras from old film canisters, loading them with photo paper. I realised that the conventional camera was not always necessary in making photographs. I went around the area and taped the pinhole cameras to poles and trees, aiming them south. I let them be for two weeks. The results were small negative pictures of the sun moving over the sky. They lacked details and were rather abstract and grainy, but I could see the trace of the sun almost burning a long hole in the photo paper. They were different to, but not totally unlike, Strindberg’s images. And what I saw in these small pictures was something that was the opposite of photography’s freezing moment – I saw the time passing.

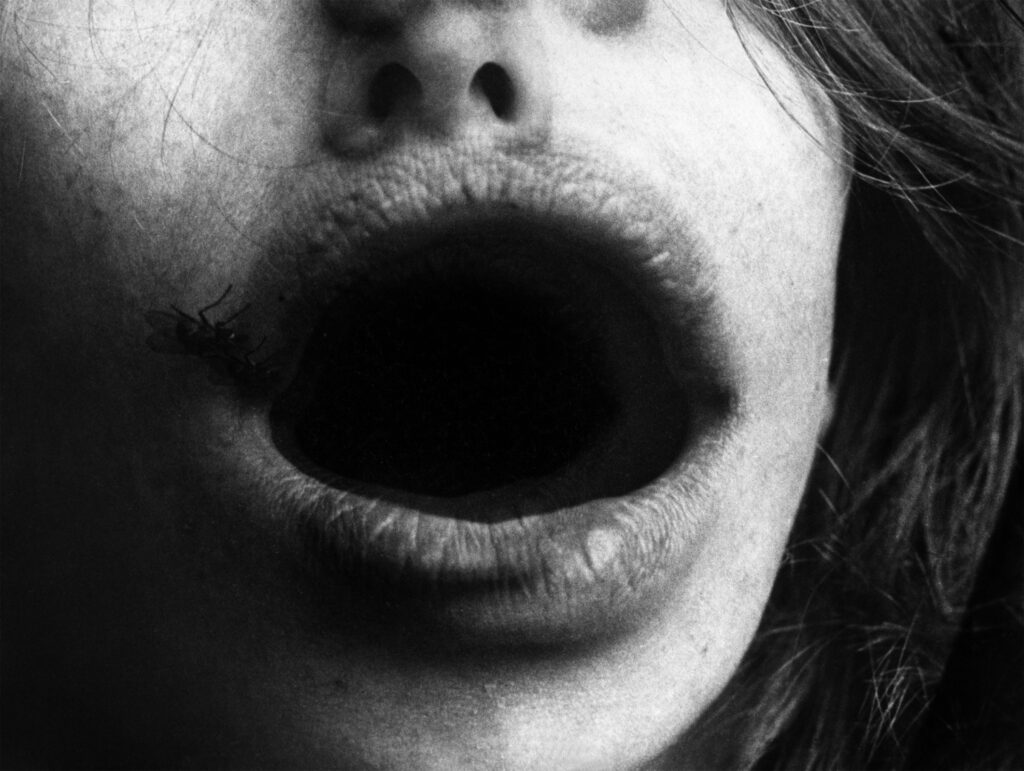

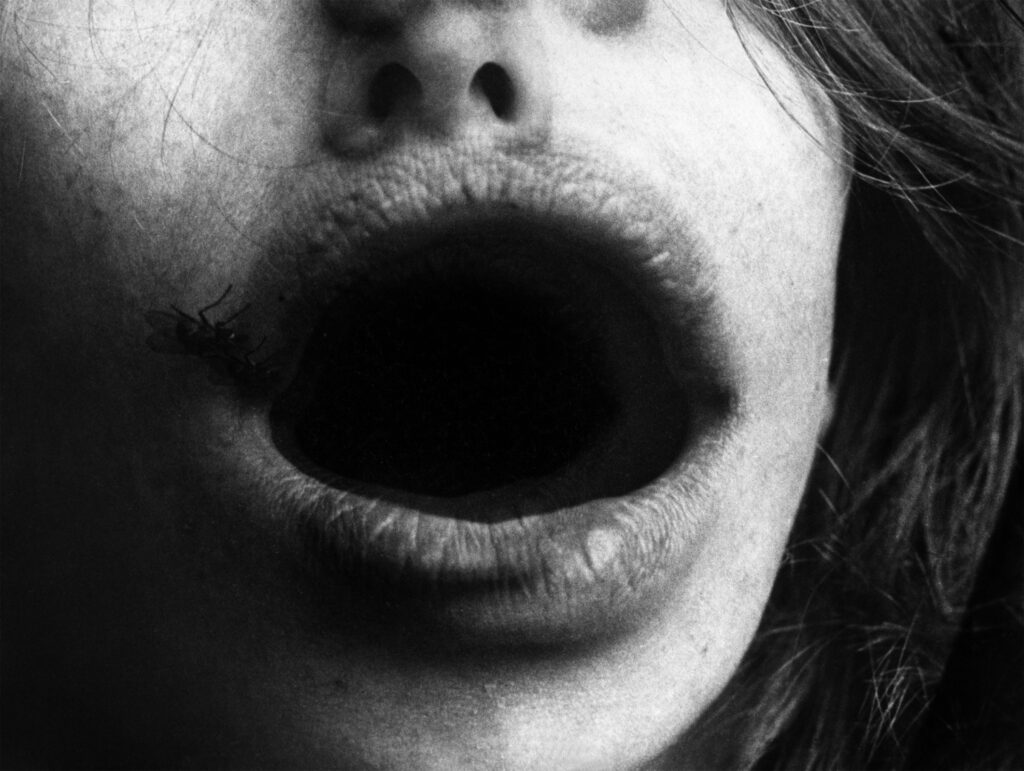

Another experimental photographic work that has been influential to me while working in Västerbotten is the book Tall-Maja from 1967. The work was made by the photographer Agneta Ekman when she was only 22 years old, and it’s been the most important reference for me in the making of my Västerbotten work. The book revolves around folk tales and nature and could be described as an investigation of the forest and the human mind through photography. The work is considered to be Sweden’s first conceptual photo book, and the photographs depict forests, trees, flowers and various portraits of people who are, for instance, dancing and screaming. They are raw and in high contrast black and white, according to the 1960s tradition. Most of the images do not contain any hints at when or where they were taken – this is left for the reader to imagine.

In the appendix to the facsimile edition of the book from 2013, Ekman describes her process of making the work. Here, she described how she made the book with a “raw intuition”. Together with three friends she went to a cabin in the woods for a few weeks and photographed. With help from each other, they staged different scenarios in front of the camera, something that Ekman explains as a kind of creative play. At the time, Ekman studied under the documentary photographer Christer Strömholm at the Photography School in Stockholm. Despite this, she was quite uninterested in the documentary tradition that was taught at the school and instead felt a closer relationship to early conceptual photographers like Bill Brandt.

Maybe it was this lack of interest in the documentary that made her able to freely experiment with the images in the dark room later on. The most striking of her images in the series are the double exposures. Some of them are very abstract, almost psychedelic, others are just plain, with two different clear motives or the same picture twice. These double exposures add another sense of reality to the image, something that a conventional photograph would not be able to show. Instead of creating a frozen moment, they create multiple layers in the same image – like a parallel reality that is happening all at once. Ekman later describes her process of creating double exposures like this:

“I don’t know why I started using several negatives on top of one another. But it was part of my wanting something more – the feeling that my imagination was present too and was just as real as the outside world. The camera’s ability to register documentary realities was not enough. Our senses are so much more than a technical registration of what happens to be in front of the camera lens.” [ii]

Ekman’s pictures are haunting and it’s impossible not to get sucked into her visual world. Her unconventional approach to photography and her lack of time markers makes the images still relevant today. Ekman had, like me, realised that the camera is a device that is constructed to depict a kind of single-dimensional reality. It is fairly easy to take a photograph of a beautiful landscape, just by aiming the camera and pressing the shutter at the right moment. But I always considered conventional nature photography to be flat and boring. Rather, I am interested in how I could translate a notion of nature, instead of a depiction of it.

In the making of the work in Västerbotten, I have been using material and tools that mostly have been new to me. The use of unfamiliar processes has for me, just like Ekman, been like a creative play. But unlike her, my double exposures had, so far, been the results of lucky accidents rather than a conscious choice.

With some of my photographs, I had already experimented with opening the camera, creating random light leaks directly on the negatives. Inspired by Ekman’s post-processing, I now tried to alter the developing process with some negatives. I experimented in opening the film tank in the middle of the developing process, creating a solarisation effect on the negatives. The results varied and were hard to control, and I decided to end these experiments. I became anxious that the photographs I’d been working so hard to capture were going to be lost forever.

Both Strindberg and Ekman stepped away from the photographic conventions of their time, actively creating room for chance to happen. Their processes were playful, exploratory and unconventional, and they both had quite an overconfident aim with their work. Strindberg wanted to reveal the secrets of universe while Ekman aimed to visualise the impossible.

One aspect that I came to think of in researching for this work is the notion of time. Both Strindberg and Ekman created works where time is barely present. It could, especially in Ekman’s work, be interpreted as a multi-layered concept – like in a dream where several elements can occur at once instead of the linearity of time in the real world. The lack of time markers gives the feeling that nature is something constant, like a realisation that nature was here before us, and will still be here long after we are gone.

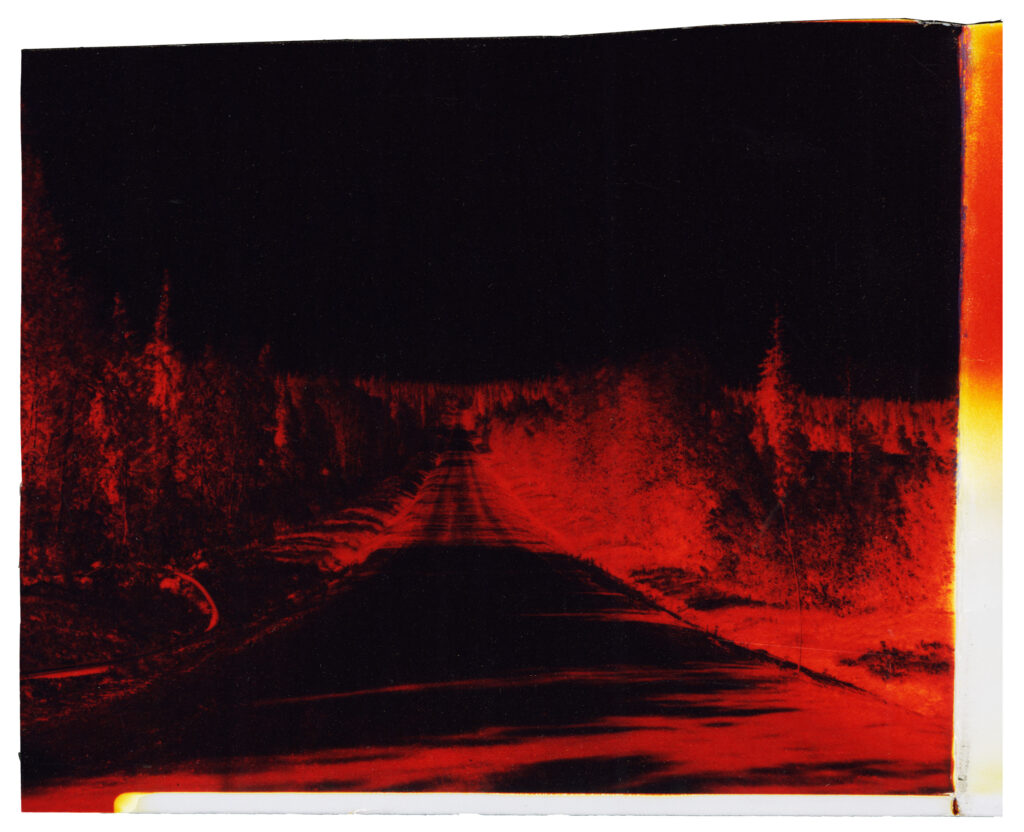

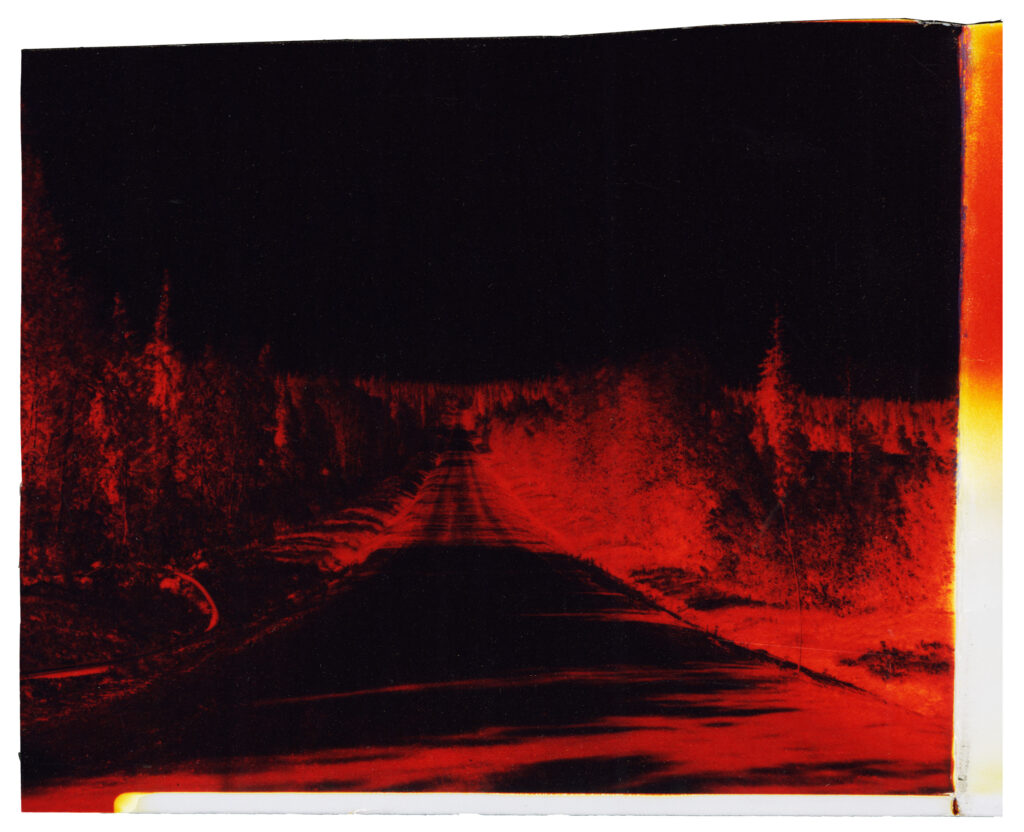

After my fruitful experiment with pinhole cameras, I decided on my next trip to Västerbotten to stretch this further. I loaded my 4×5 camera with photographic colour paper and went out into the forest. I had never done this before, and I had no idea how the results would turn out. But I aimed right. When I later developed the prints, the results were stunning. The photographs showed haunting red and black negative images whose appearance led me to think of infrared photography used by the military, like a different reality that was only visualised through these photographs.

In the work with this project I have been struggling with how to do the location justice without getting blinded by the sometimes breath-taking landscape. How do you depict something that is so beautiful and that has been photographed a thousand times before? For me, it came through the people populating it. Through portraying and having conversations with people, I gained another understanding of the local history and the landscape. These conversations became influential in the making of the pictures.

I have visited Västerbotten four times for this project, but I feel that I am just getting started. It is still a long process that I am in the initial phase of. To create a real bond to a place and its nature takes stubbornness and a large amount of time. Luckily for me, these two elements happen to be my richest resources.

In the works I’ve been looking at, the artists have used photography in an experimental way, pushing its reality-recording capabilities into something else. Whether or not their main topics differ, they have all made works based on their perception of nature and the intangible aspects of the world surrounding us. And they have all actively used chance in the creation of their works. Whether it is with post-processing, double exposures, different kinds of cameras or the lack thereof, they have all found ways to create experimental photographs that push the idea of what photography and our perception of nature can be.

My own quest for nature has just started, and I will continue my photographic exploration of it. I want the viewer to feel what I felt standing at the top of a mountain, photographing the stunning landscape below. I want the viewer to hear the sound of the water flowing in the river. I want them to hear the sounds of the reindeer bells. But most of all, I want the viewer to understand the magic of my grandmother’s stories.

The last time my grandmother visited her home village was together with my mother a few years before she passed away. The trip was a last goodbye to her childhood home; we all knew that she would not be able to make the long journey again. During this trip, my mother saw her own mother in new light. The restlessness was gone, and her shoulders relaxed. She was at ease with herself. “She was natural there,” my mother said, “It was here, in the nature of Västerbotten, where she obviously belonged”.

One day I hope to belong there as well.

References:

Bengtsen, P., Liljefors, M., and Petersén, M., Bild och natur, Tio konstvetenskapliga betraktelser. Lund studies in Arts and Cultural Sciences. 2018.

Feuk, Douglas. August Strindberg: Inferno Paintings and Pictures of Paradise. Edition Bløndal, 1991.

Strindberg, August, Tryckt och otryckt IV, 1897.

Strindberg, August, Du Hasard dans la production artistique. La Revue des Revues. 1894.

Ekman, Agneta, Tall-Maja, Journal förlag (2nd ed), 2013.

Ekman, Agneta. Artist Interview. Dagens Nyheter. 2016-08-09.

https://www.dn.se/kultur-noje/agneta-ekman-malar-med-fotografi-igen/ (Accessed 2020-04-20).

Ekman, Agneta. Artist Interview. Fotografisk Tidskrift. 2014-01-29.

https://www.sfoto.se/portratt/fotofika-med-agneta-ekman/ (Accessed 2020-04-20).

Author unknown. August Strindbergs photographs. Fotografisk Tidskrift. 2012-03-07.

https://www.sfoto.se/nyheter/fotografen-august-strindberg/ (Accessed 2020-04-20)

Nathéll, Ingrid. August Strindbergs photographs. Sydsvenska Dagbladet. 2012-01-20.

https://www.sydsvenskan.se/2012-01-20/forfattarens-foton-i-fokus (Accessed 2020-04-20)

Olsson, Ulf. Paper about August Strindberg. 2019.

https://riksarkivet.se/publikationer?item=11392 (Accessed 2020-04-20)

[I] Strindberg, August, Tryckt och otryckt IV, 1897. p.241.

[II] Ekman, Agneta, Tall-Maja, Journal förlag (2nd ed), 2013. p. 120