I Think I’d Like to Stay Here for a While: Forever Searching Within Family Albums

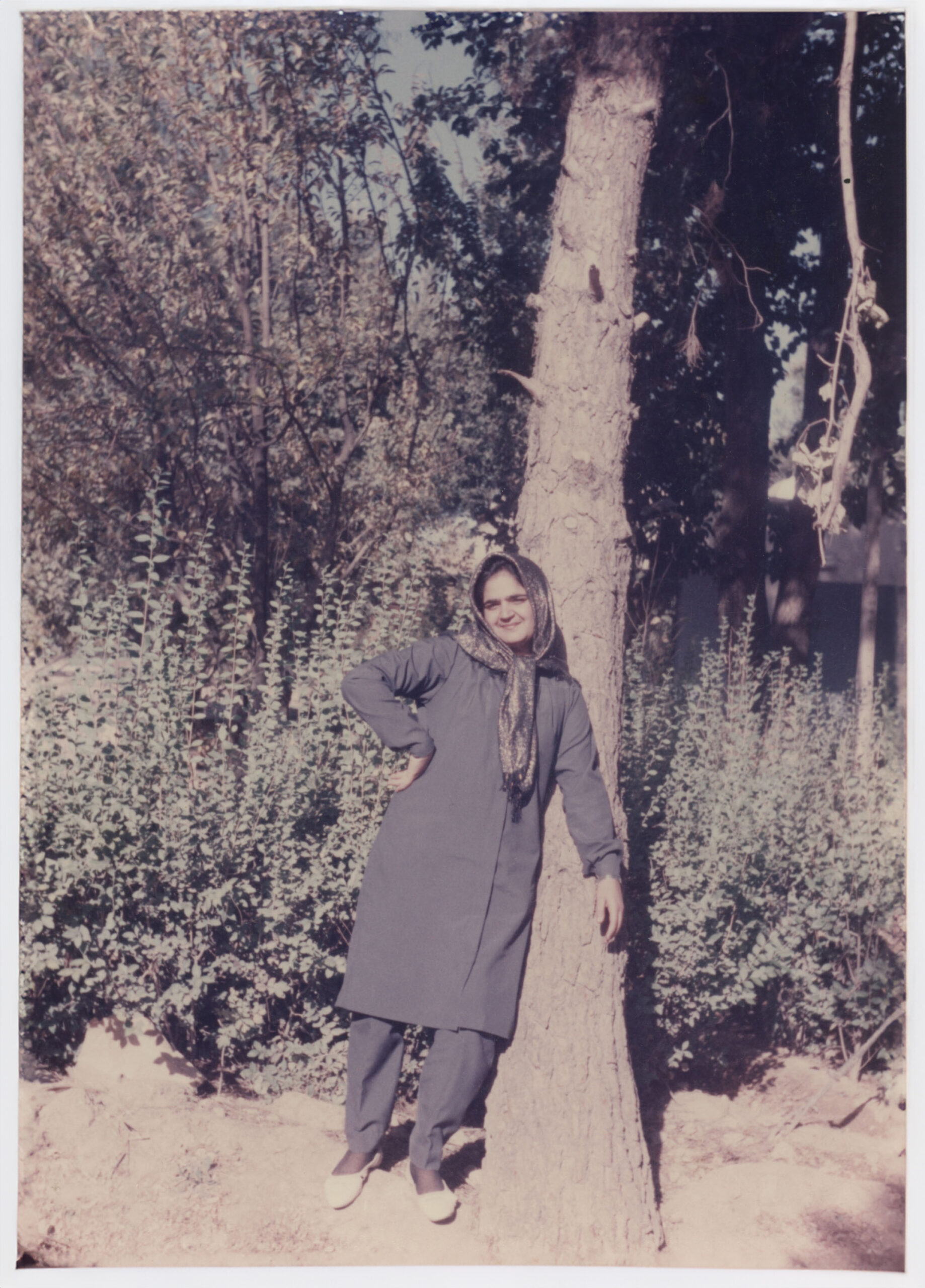

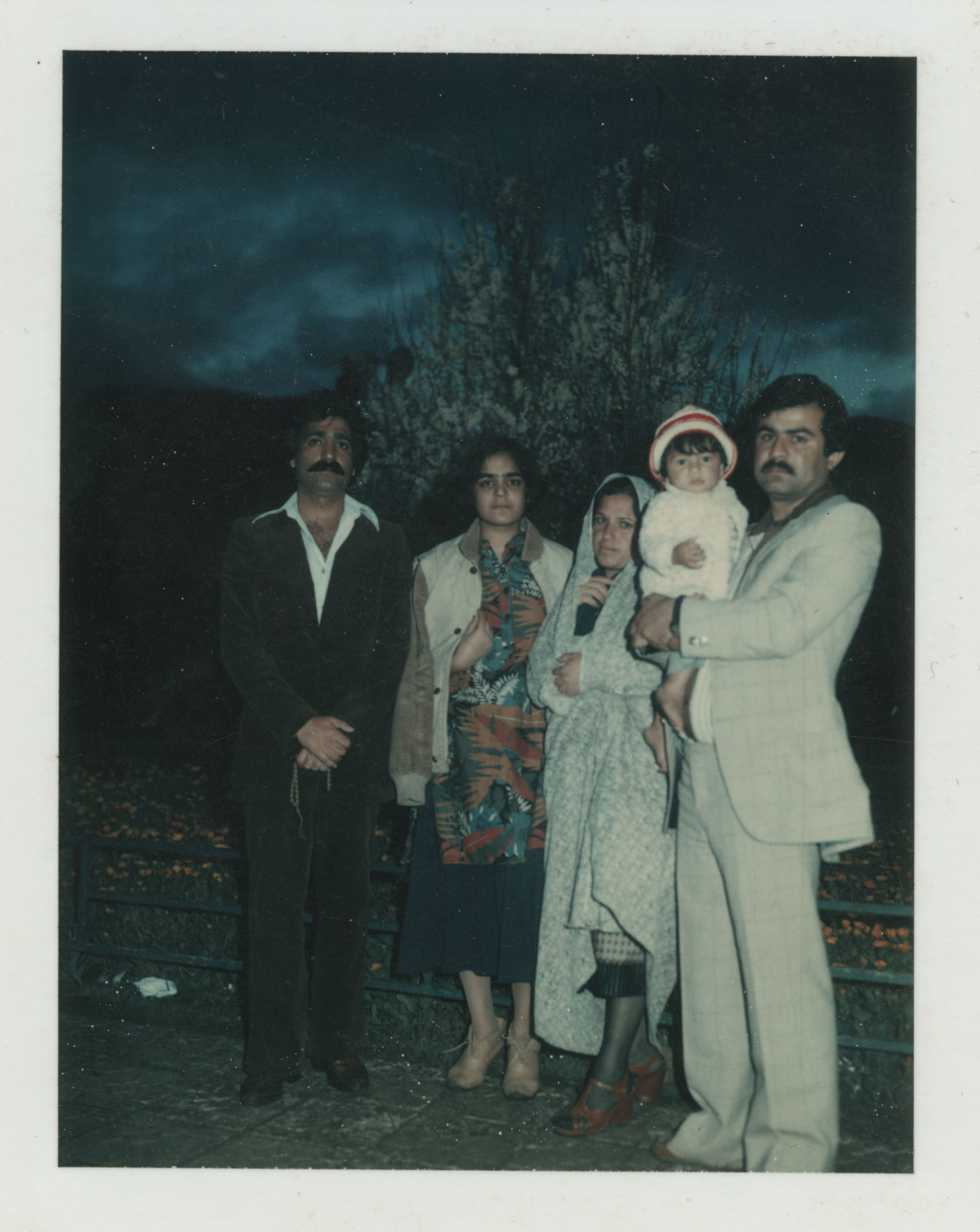

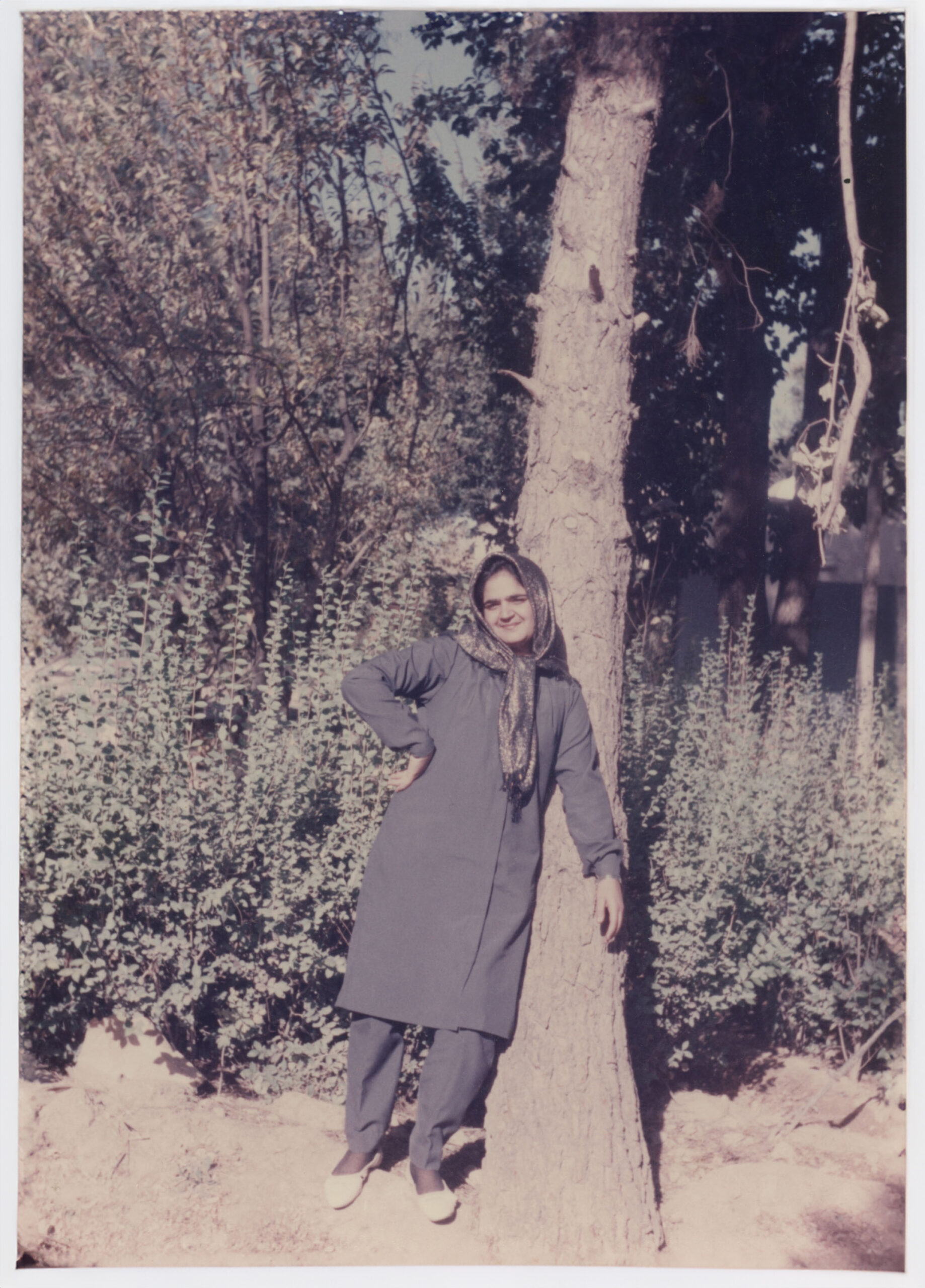

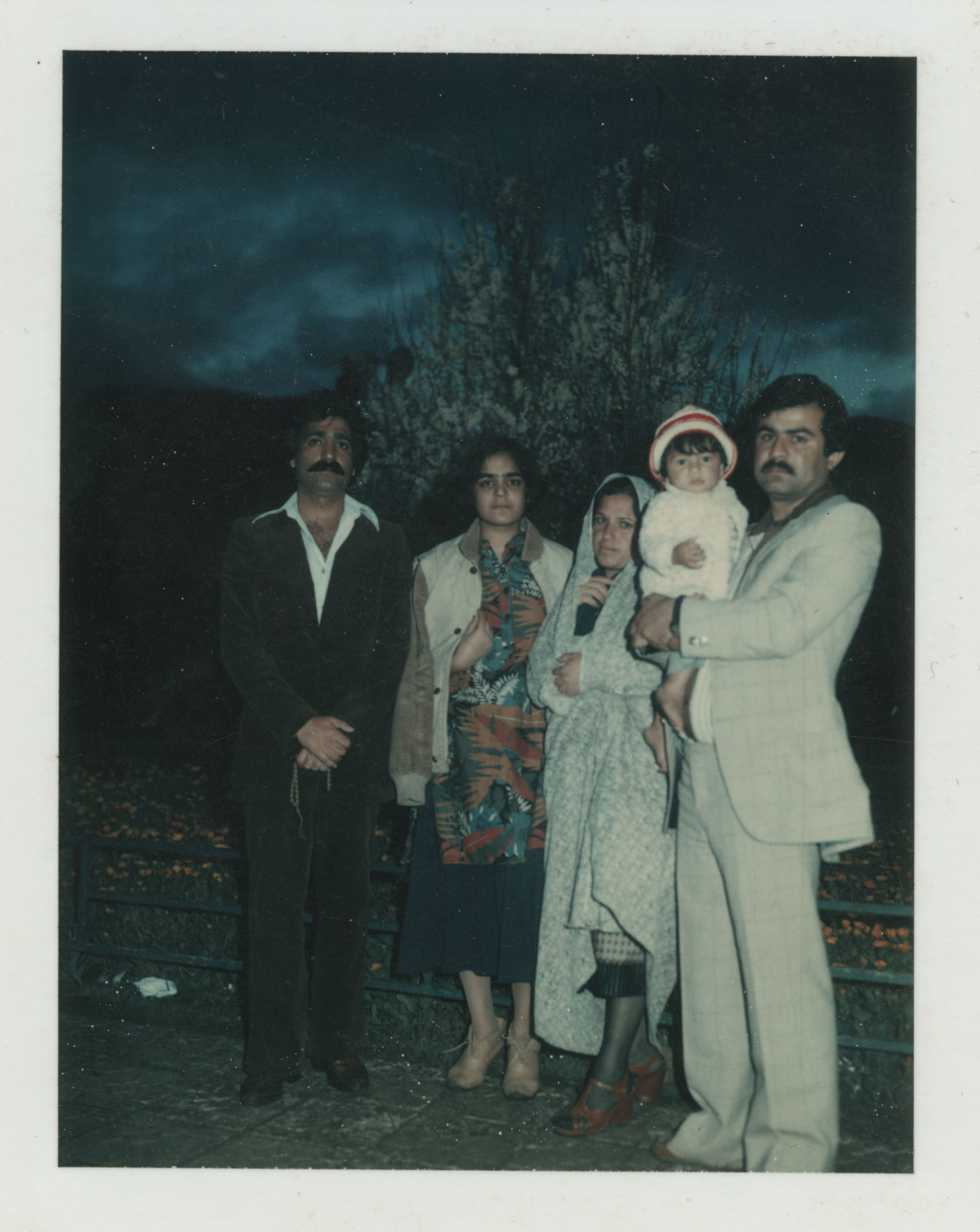

Every time I go back to Malmö to visit my mom, I have a habit of going through our family albums. Regardless of whether I’ve flipped through every album and every messy box of loose photographs hundreds of times by now, there’s always something new to discover, some detail that I may have missed or forgotten. It’s like a manic search for something. When I flip through these fragments of memories, I am transported to Iran: all the streets, all the bazaars, all the mehmooni’s (parties), and my mom’s face resembling mine. I find solace in the collection of photographs from my family’s past in Iran. Each faded photograph becomes like a portal to a time and place that I may otherwise never have known.

Recently, I came across Nazanin Raissi, an artist and psychologist based in Gothenburg. Her work centers on photography, exploring themes of memory, time, loss, and belonging. What Nazanin and I share is an interest for exploring and working with family archives and albums, as well as our common origin from Iran. Nazanin’s work immediately piqued my interest, and I felt the need to meet her to discuss the meaning of the family album and its resonance within us. Being able to exchange thoughts with someone who dives into the complexity of the family album in the same way I do provides a sense of liberation and understanding. The purpose is to clarify my thoughts and feelings through this interaction. We meet to converse.

Nazanin shares her fascination with the family album and emphasizes its significance with a clear emotional value, which I can also relate to. She reflects on how the family album represents a pursuit of something unfathomable, an existential quest that may never receive a complete answer. We delve into a discussion about how our parents, despite their closeness, can be strangers to us, and how observing their lives before our birth through these images generates a complexity of thoughts and feelings about our identity and heritage. In our dialogue, I also discover how strongly memories and nostalgia are intertwined with our relationship to the family album. It serves as a reminder of the past and of our own history. Our discussions lead me to deeper reflections on the significance of our roots and how they shape us as individuals.

When I was growing up, I wasn’t always aware of the value and significance of my background and history. I remember often striving to fit into the white Swedish society, attempting to assimilate into the culture that surrounded me. In that pursuit, my own culture and history were sometimes downplayed, as if they weren’t as important or relevant. It was as if I, to some extent, denied my own identity to meet society’s expectations and norms. I didn’t want to stand out; I didn’t want to be different. So, I ignored or diminished the heritage my family had to offer, and I avoided learning about my culture, my history, and where my family truly came from. The family album, filled with old photographs and memories from generations before me, became almost like an object from another world. I didn’t want anything to do with it; it reminded me of my different background, something I wasn’t sure I wanted to embrace. Instead of exploring the album’s pages and letting the pictures speak to me, I tried to ignore them and pretend they didn’t exist.

Pictures from my own childhood don’t affect me in the same way, I mean in the sense that I actually experienced those moments. There’s a particular feeling when I flip through the pages and come across pictures from my childhood. I recognize the places, I recognize the people, but still, I feel a distance from the little girl playing in the photos. It’s like I’m observing someone else’s life, someone else’s memories, even though I know they’re mine. It’s when I look at pictures of places I’ve never been to and people I’ve never met that something changes. Then, my curiosity comes alive, a longing for the unknown. Why am I drawn to these pictures, to places I’ve never visited and people I’ve never known? Perhaps it’s because they represent something I have yet to discover within myself. Each picture then becomes an opportunity to approach the unknown and explore new parts of my history and identity.

I believe there’s something special about the tactile experience of flipping through a physical family album that can’t be replaced when viewing pictures on a phone or a screen. It’s as if the intimacy and depth inherent in the act itself disappear when trying to digitize memories. I particularly think about the empty pages in some of our albums, where my mom removed pictures of my dad after their divorce, or even cut him out from certain photos. The physical act of removing or clipping pictures from a family album wouldn’t feel as vulgar as deleting them from a phone. There’s also something unique about there typically being only one copy of each picture in the album. Every photograph feels more valuable and significant, as if it’s a unique treasure that must be cherished and preserved for future generations. The album somehow becomes their home, their safe place where they get to live on.

My continuous pull towards the family album and my dependence on flipping through its pages is something that has occupied my thoughts extensively. It’s as if I’m trapped in a perpetual spiral of thoughts revolving around the fear of loss and destruction. My concern that things will disappear or be lost follows me every day. When I think about life, I often think of it as fragile and vulnerable, and that realization has penetrated my consciousness in a way that’s difficult to explain. When I see images and videos of the unimaginable suffering that people experience in wars or genocides like Palestine, it’s as if my own memories and experiences take on a new meaning. I think about my family, about the place where I come from, and about how quickly everything can be changed and destroyed by human hands. It’s sobering to think about all the family photos that are destroyed and how the visual heritage disappears in the shadow of ongoing genocide or war. I think about those who survive, about their struggle to remember and honor their families, relatives, and their cultural identity without losing hope or being drowned in grief.

Photography plays a role in preserving culture and the heritage of generations. It functions as a time capsule capturing moments and narratives. As family albums slowly fade away, we risk losing a valuable part of our history. In addition to losing the visual representations of our ancestors and past generations, we also lose the stories told through these images. By flipping through these albums, we gain insight into the lives of our ancestors, their culture, and traditions, helping us understand our own heritage.

As I delve into the photographs and contemplate their significance, I cannot help but recall Roland Barthes’ words on photography. Barthes describes photography as an intrusive illusion of presence, and that’s precisely the feeling I experience when I examine old family photos or pictures from distant places. This “illusion of presence” allows me to step into another time and place, feeling intimately connected to the people and events depicted, even though I have never experienced them myself. It’s as if the photographs breathe life into the past, enabling me to relive it in a new or entirely different way than reality, even if only for a brief moment.

Images: Gloriya Talebi

References

Raissi, Nazanin; Artist and Psychologist. 2024. Conversation March 14th.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida : Reflections on Photography. New ed., 1993.