Overcoming Image Fatigue: Non-representation in Analogue Cameraless Photography

The rate at which we now communicate with images online almost defies comprehension, with 290 billion photographs uploaded daily to Facebook and Instagram in 2018.[1] It could be said that we live now in an age of image overload, of visual overstimulation and of pictures that we consume mostly via illuminated glass screens. For most people, the physical photograph is now a thing of the past, and many artists working with photography have understandably made the move to the cheaper, more accessible and more pliable digital medium. Beyond standard digital photography, photographers are harnessing new technologies to create their art; for example, Rob Munday’s 3D holograms of flowers and Aydin Büyüktaş’ warped drone landscapes. Mat Collishaw, who created a virtual reality version of an 1839 William Henry Fox Talbot photography exhibition, predicts that such technology will have the same revolutionary impact on the art world as photography itself did.

Yet despite the prevalence of new technologies available to photographers, many are returning to the original DNA of the photographic method, the grass roots, the experimental processes that were used by innovators of the medium such as Louis Daguerre, John Herschel and Talbot. This return to the origins of photography isn’t quite as straightforward as simply using a camera to produce a physical negative instead of a digital file; many artists seem to be increasingly drawn to photography’s ‘building blocks’, its genetic make-up: emulsion, light and paper. But hasn’t everything that can be done with these ingredients already been done in the intervening 180 or so years since Louis Daguerre harnessed the light-sensitive properties of silver salts? Why is it that photographers continue to cling to these archaic methods in the face of abundant new technologies?

I first turned to cameraless methods myself when I started a research project in which I intended to represent my problematic relationship with the internet, the absorbing virtual universe that tends to be rich in text, colour, detailed and visually complex still and moving imagery. What photograph could I possibly take that could encompass the internet in all of its visual complexity? How do you photograph the internet, and the complicated relationship it has to the human body and the mind? For me, a potential answer lay in utilising the internet itself in creating an image – or rather, the device which is a portal to the digital world, my smartphone. On the other hand, I also wanted my practice to take me away from the screens that had become what felt like an overwhelming component of my life, so I headed to the darkroom. When I arrived there, a compromise emerged, synthesising my problem and its solution: introducing the screen of my phone to the surface of the light-sensitive paper in a controlled way blocked my access to the device as I simultaneously used it to paint an image into being (see figs. 1 and 2).

The earliest experiments in the development of the photographic medium began in a similar way, with a sense of curiosity about what happens when you introduce light to silver nitrate solution, for example, coupled with the instinct (and backed up by scientific knowledge) that something will happen. Back in the mid-19th century, the earliest innovaters, the likes of Talbot and Daguerre, toiled away over their solutions of salt and silver or mercury and silver iodide, striving for detail in their imagery and racing to be the first to produce a crystal clear representation of the world that would remain permanently fixed to its paper or glass plate. In contrast, many contemporary artists who work with photographic materials seem instead to be striving for lessdetail; blank sheets in varying shades of cyan in Nanna Dubois Buhl’s Collected Walks (2012), or the abrupt fade from black to white in Broomberg and Chanarin’s The Day Nobody Died (2008), long scroll-like prints edged by ragged jags of colour formed by light interference. The large-scale photograms of Liz Deschenes’ Gallery 7 (2014) are, like many of her works, nothing but sheets of colour, unfixed and therefore encouraged to transform during their exhibition – exactly the opposite of what Talbot and co. aimed to achieve. In The Day Nobody Died, Collected Walks, and Gallery 7, figurative representation is eschewed entirely, refusing the focus provided by the lens, the accuracy and measurement offered by camera apparatus; instead, the artists generate the works with only light and reactive paper.

Abstraction in these works appears to be a deliberate and outright refusal of the index as we know it, with no visible referent to cling to and the ‘imagery’ telling the viewer very little; however, the gestures surrounding the works’ production are loaded with meaning. The Day Nobody Died (see fig. 3) was created when Broomberg and Chanarin travelled to Afghanistan in 2008 to be embedded as conflict photographers with British army forces on the front line in Helmland Province. Rather than taking photographs, however, the pair created abstract luminograms by exposing a roll of photographic paper to the light. So, when a soldier or civilian suffered a violent death, or when a more mundane event occurred such as a press conference that would usually be photographed in a conventional way, the only photographic record is a vague colourful rendering of light upon paper. These results are both beautiful, and nothing. Their abstraction is frustrating, their means of production outrageous to some such as photography critic Sean O’ Hagan, who described the process as an arrogant stunt – and the artist’s description of co-opting the British Army into their ‘absurd performance’ does indeed seem somewhat patronising. It’s true, though, that the works’ mystique encourages reflection and engagement; we wonder at how they were made, and why. The sensuousness of the non-images serves as an inroad, and then a catalyst for thinking around the long relationship between photography and suffering. The prints are as impeding as they are absorbing – blocking us from bearing witness and yet making us think about war without seeing it in front of us, as we are used to.

There is a potent indexical power to these photograms as objects which have been there, and which have borne witness to suffering that (unusually) we as viewers are in this instance denied access to. The traditional referent object that appears in front of a lens is displaced: here, it is the photographic material itself that is both referent and index, discounting entirely the notion of power relations between photographer and subject, while the rejection of the figurative unburdens photography from the debate on representation that has dominated discourse in the field for decades. Denied a referent, we as viewers are forced to see this photogram instead as a witness as defined by Max Kozloff, “with all the possibilities of misunderstanding, partial information or false testament that the term ‘witness’ may be taken to imply.”[2]

Why analogue materials, though? Of course, emptiness can be conjured through digital means too. Broomberg and Chanarin’s cloaking of reality could also have been performed using digital techniques, a central subject later removed from a digital image in Photoshop, for example. But there is just something that feels less organic about digital intervention: has that TIFF file really, actually been there? In The Day Nobody Died, the roll of paper becomes a character in the artists’ narrative, an idea expanded upon in a film accompanying the physical works in which we see the roll of paper transported through airport luggage carousels and through the desert landscape. There becomes a sense that this paper, coated with layers of colour emulsion to soak up light, could also absorb some ephemeral element of the atmosphere. Variations on this fantastical idea have existed since the early days of photography. In the late 19th century, a retired French soldier named Louis Darget strapped photographic plates to people’s foreheads when they were sleeping, believing that the resulting vague wisps of light that appeared on the print were a visible manifestation of their dreams. Later, in 1929, a spiritual medium named Madge Donohae pressed photographic plates to her face, resulting in odd circular impressions of light which she claimed to be “a visual code sent from the spirit world”.[3]

Of course, that’s impossible. But perhaps we somehow still need to believe that there is a means of recording some aspect of life’s essence that is unseeable, unknowable. We know by now that the camera lies, but we are conditioned to understand that the images we see contain some element of truth – and whether or not we believe that, we are exposed to a staggering amount of images on a daily basis. The sheer volume of imagery we consume arguably has an anesthetising effect on viewers,[4] when in fact the opposite is intended, as is often the case in conflict photography; to jar us out of apathy and into action. Maybe we need a break from processing so many images, a pause which could perhaps be provided in a blank space with a hint of colour, allowing a moment for reflection and a place in which our own thoughts, ideas, and daydreams can manifest.

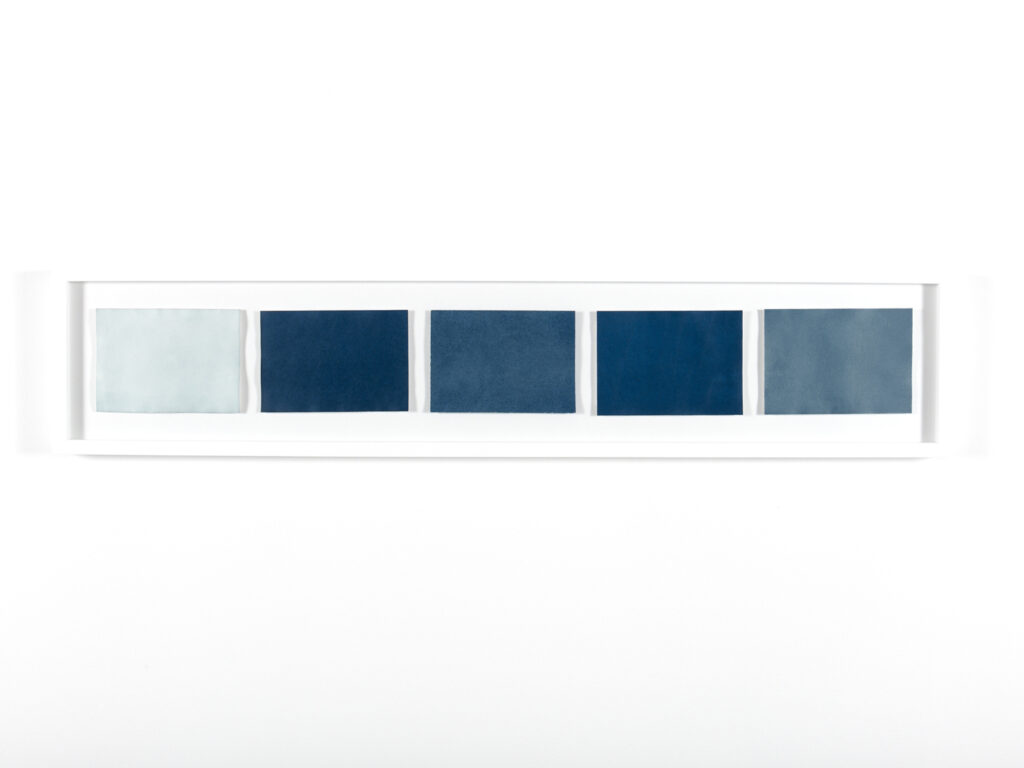

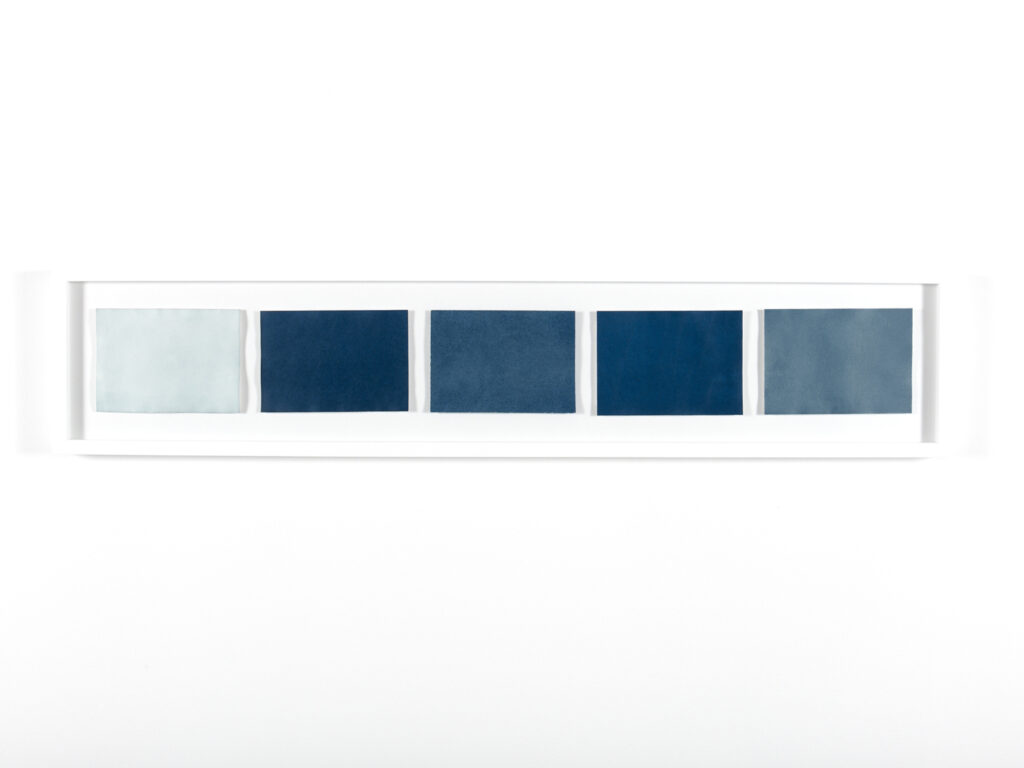

Nanna Debois Buhl’s Collected Walks (2012) is a series of cyanotypes created by the artist as she took walks through different cities, exposing the chemically treated papers to the light as she walked. The results, rectangles of varying shades of plain blue, are exhibited grouped together in frames (see figs. 4 and 5). While the walks were performed in different cities, each grouping appears more or less the same, and the sheets of paper, blank besides their colour, really tell us nothing about the cities Buhl was walking through. The vibrant, bustling city streets, which have long been a favourite subject of photographers the world over, are here denied to us. The only thing that could be discerned (and only by those with an understanding of the mechanisms of photography) is that the darkest blue sheets were produced when the sun was shining, or perhaps during a longer walk.

Why does Buhl choose to show us this blankness instead of the life of the streets? On her website, Buhl describes the cyanotypes as “a diary or logbook… each print an abstract registration of the weather and light conditions at a given time and place”.[5]Again, this gives us the sense that the paper itself is capable of capturing the experience of walking through city streets, an experience that can occasionally possess a potency that it is hard to describe in representative imagery, particularly when walking the streets of an unfamiliar city for the first time.

As with the film accompaniment to The Day Nobody Died, Buhl’s cyanotypes have a companion piece which complements the performative production of the work, an audio collection of literary quotes about women walking through different cities by writers such as George Sand, the 19th century noblewoman and author who found she was able to wander more freely in Paris when wearing male attire. The audio is suggestive of another layer to the work regarding the presence and absence of women in public space, and the societal rules which might limit their ability to move through the world freely in both historical and contemporary settings. The absence of detail in the cyanotypes coupled with the audio excerpts perhaps remarks on how, historically, women’s experience of being in public spaces has gone under-documented when compared with male experiences. Now, of course, things are quite different; if we travel to a different city, it feels that there is an inherent expectation to document and share our experiences visually on Instagram, for example. Buhl’s refreshingly blank cyanotypes could be viewed as antithetical to this contemporary desire and expectation to collect ‘experiences’ through social media sharing, and instead to simply have experiences without feeling the pressure to document them.

A feminist reading of cameraless photography is also applied to the work of Liz Deschenes by Eva Respini, who views much of contemporary experimental work in photography by female practitioners as an act of defiance. As an art form that was (and sometimes still is) seen as ‘other’, photography was historically an accessible medium for some women because it didn’t have the same tradition and social prestige as revered art forms such as painting and sculpture: “In its infancy, photography was practiced by scientists and alchemists, not artists. A photographer didn’t have to be enrolled in the hallowed halls of the academy; she could cook it up in the kitchen.”, says Respini.[6] Deschenes, who produces large-scale cameraless works, agrees that her outsider status as a woman has contributed to her creative approach: “It does not make much sense for women to follow conventions. We have never been adequately included in the dialogue around image production.”[7] Respini suggests that this defiance manifests in doing something outside of the norm, and it is demonstrated also in the physicality and scale of Deschenes works, which often stand taller than the viewer, confronting them in the gallery space, as seen in her Gallery 7 (2015) works. These photograms are created using a unique process devised by Deschenes in which she exposes photosensitive paper to the night’s ambient light, and then washes the paper in silver toner, creating a metallic, mirror-like effect (see fig. 6). In the gallery, the only figurative element of the work is the viewer’s own vague reflection in it, a kind of live, real-time referent.

Over time, the colour and reflective sheen transform as the unfixed materials oxidize. These are photograms that, according to one reviewer, “absorb phenomena – light, shadows, the presence of viewers – beyond Deschenes control”.[8]

The issue of control, of letting go, is a central factor in all of the works discussed. Despite the meaningful gestures surrounding the works, ultimately, some of these artists simply open the box of papers and let the light go to work on them. It’s not only photography that is unburdened from the responsibility of representation, but the photographers themselves. It would be easy to view this as indicative of some unwillingness on the part of the artists to engage with the complex ethical issues that confront all photographers. Yet the gestures surrounding these works reveal that there is meaning in the emptiness, and the poetic aesthetic of blankness acts as a lure, inviting us first to look, to imagine, and then to think and uncover the pertinent topics the works explore – war, censorship, women’s untold histories and the complicated histories and responsibilities of the photographic medium. In contrast, it could be argued that contemporary engagement with on-screen images leaves little time for the imaginative thought which is central to the works discussed here, in which you’re shown a mystery, a riddle, and have to puzzle it out.

The processes used by these artists are only a few steps removed from those developed in the mid-19th century to conjure photography as we know it today into being, and such methods have endured now for almost 200 years. Just as sculptors and painters continue to create with marble and oils, it seems likely that photographers will continue to soak up the world around them by directing light towards emulsion, despite the prevalence of new technologies.

Blankness should not completely replace the images to which we have become accustomed and which are still necessary to see, however painful or complicated they might be. Instead, blank abstracted images provide a space for the eyes to rest and for organic thought to emerge, before we plunge back into the daily routine of ‘image overload’ once more. Unburdened from photography’s representative role, the spaces provided by The Day Nobody Died, Collected Walks and Gallery 7 allow for reflection and imagination, while through the materials’ presence at the site of creation and their creation through performative alchemical processes, they become powerful phenomenological art objects whose materiality records the unseeable and unknowable.

Illustrations

Fig. 1. Lauren Spencer, 2019

Fig. 2. Lauren Spencer, 2018

Fig. 3. http://www.broombergchanarin.com/installation-the-day-nobody-died

Fig. 4. http://nannadeboisbuhl.net/walks/

Fig. 5. http://nannadeboisbuhl.net/walks/

Fig. 6. https://walkerart.org/calendar/2014/liz-deschenes

References:

[1] S. O’Hagan, ‘What next for photography in the age of Instagram?’, The Guardian, 14 October 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/oct/14/future-photography-in-the-age-of-instagram-essay-sean-o-hagan (Accessed 20 March 2020)

[2] D. Price and L. Wells, ‘Thinking about photography: debates, historically and now’ in L. Wells (ed.), Photography: A Critical Introduction, 5th edn.London, Routledge, 2015, p. 34

[3] G. Batchen, Emanations: The Art of the Cameraless Photograph, DelMonico Books-Prestel; Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, 2016, p. 16.

[4] S. Sontag, On Photography, London: Penguin, 2014 (Kindle edition), p. 20

[5] N.D. Buhl, Collected Walks, [website], 2012, http://nannadeboisbuhl.net/walks/ (Accessed 13 January 2020)

[6] E. Respini, On Defiance: Experimentation as Resistance, Aperture, no. 225, 2016, p. 105, www.jstor.org/stable/44404717.

[8] A. Greenberger, ‘Photography Has Always Been a Hybrid’: Liz Deschenes on Her ICA Boston Survey’, ARTnews, October 12 2016, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/photography-has-always-been-a-hybrid-liz-deschenes-on-her-ica-boston-survey-7043/ (Accessed 15 January 2020)