Photography and bodily identity

The pronouns that I use are he, she, they/their or loosey-goosey (ft.1) depending on each artist’s and theorist’s preference.

Photography, a constructed language.

As a lens based artist working mainly with self-portraiture I experienced the limits of the photographic medium really early on in my practice, along with the limits of my body. Being bodily engaged into your practice was and still is a really ambiguous experience for me. When I work on the character/role preparing it for the camera and later on performing it, I feel that I am exploring unrevealed sides of my identity. I am looking at a version of myself that does not belong to me anymore and it is nothing else but a photograph. I wonder sometimes if I could describe it as the dead cells of our skin that we get rid of them when we are rubbing our skin. The outcome is liberating and suffocating sometimes. I am not just leaving a part of me feeling lighter afterwards but there is a picture to remind me of the very specific shape of my existence. I remember Elina Brotherus saying in an interview that she got shocked the first time she saw herself in a photograph. She had a different idea of what she looked like. (ft.2)

But does the medium reveal just sides of us or also shape them? Does the photographic camera re-introduce us to ourselves instead of just depicting us?

Photography is a visual language that creates narratives and frames notions. Like any other form of art and communication it is an extract of the western culture and at the same time it shapes and reproduces the identity of the culture that created it. It works in a similar way with language. The American philosopher and gender theorist Judith Butler phrases in their essay Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex “the prior to language is offered within language” (ft.3). They were mostly referring to the notion of sex and how language has shaped it even though it was created to describe it. An oxymoron circle that limits our perspective within the shapes that it creates.

The activists of the Feminist Archive in 1978 embraced this idea with alternative spellings such as wymn or womyn instead of women underling the importance of linguistics in their battle against patriarchal standards.This act expands Butlers’ statement and lead us to the writer and Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity, Gender Studies and Comparative Literature at the University of Southern California Jack Halberstam who claims that we have to unlearn the existed narratives in order to create a new one.

In photography and visual arts there are a lot of artists that also query our visual vocabulary by creating new narratives and invite us to the unlearning process.

Visual art questions identity

Alix Marie (b.1989) is a French artist based in London. She works with photography and sculpture and with a focus on the human body. Within her work she creates new narratives on the body and expands the boundaries of the photographic medium itself. She shifts the body into an image and the image becomes a photo-sculpture, the subject and the medium lose their initial identity and invite the viewer into new perspectives.

In 2019 in her solo show Shredded in London she presented images of three male body builders’ bodies in a context of amputation. Photo-sculptures of body builders’ body parts like animal meat on the grill or mounted and placed in shallow vitrines, invited me in a place of transformed dehumanized bodies into material for visual consumption.

Besides Shredded her work is consists mainly of skin and body parts images transformed into site specific installations. The skin close ups and their enlarged prints on the wall shock the viewer and lead them into the limits of abject. With humor and ingenuity she shifts the bodily identity and the standards of representation. You see something familiar and at the same time you cannot recognize it. The prints on fabric and the photographic sculptures are a discourse between the subject and the material. She invites the viewer in new narratives both of the human body and the photographic medium itself. She uses the means of construction in order to deconstruct an established visual vocabulary. She intrigues our perception of the human body.

The French artist Stephanie Solinas (b.1978) is based in Paris and works also with photography and sculpture. In her piece Les brills I found a connection with Alix Marie’s pieces but in a less grotesque way and I would say mostly humorous and straight forward. The installation is constituted by four frames portraying silicon casts of belly buttons which they are placed on a living room assistant table and accompanied with the subtitle Why the face to represent identity. She uses the stereotypical visuals for the preserved memory and she tricks our subconscious. We still watch something we can identify at the first glance but our reading is being poked.

On the discussion of the bodily identity though it is important to add the gender aspect. In the publication Doing Gender in Media, Art and Culture there is a collection of essays discussing gender in Art and I found intriguing what Marta Zarzycka states in her essay “Cindy Sherman confronting feminism and (fashion) photography”: “…the materiality of the body restricts the artist and prevents her from being totally detached from her image. Being white, she only explores white femininity. Being a woman, she almost always presents female figures. Sherman occasionally escapes those restrictions by using artificial parts, masks, or mannequins, but still her photographs prove that we almost never experience ourselves out of our bodies.”. That thought lead me in two directions. On the one hand I agree that our bodies can be very specific, someone could not become taller than he/she/they is/are or could not change race. But on the other hand they can be very fluid. Everyone has a very unique way of experiencing their body but the interventions that someone could do are radical. The body is our boundary but not our limit. Queer artists and theorists who have enriched the perspective of the body have added “a view from elsewhere” like Sin Wai Kin described (ft.4). Sin Wai Kin (b. 1991, Toronto CA) is a Canadian artist based in London. Their work could be described as an offspring of Cindy Sherman’s in a mix with pure drag art. Sin Wai Kin introduce themselves as Victoria Sin and reenacts characters from Western female stereotypes and ethereal male figures. In an interview with Nowness, they describe their act and drag art in general as a “blow up” of the gender. Photography here is just the mean of documentation. The medium that shaped the role model stereotypes now it is used to blow them up. In Sin’s case it is not the medium that is questioned but our visual vocabulary. The visual vocabulary that defines what a woman or a man looks like. In Back to Earth: Queer Currents episode of the Serpertine podcast, Sin participates in a discourse with Ama Josephine Budge, Macarena Gómez-Barris and Jack Halberstam on queer theory, environmental activism and climate justice where they underline the importance of reframing , moving away from absolutes and embracing the queer view as another perspective.

J. Halberstam has a really interesting jumping off point from Gordon Matta Clark’s work to the transgendered body on his essay Unbuilding Gender: “…we might take up the challenge offered by Matta – Clark’s anarchitectural projects in order to spin contemporary conversations about queer and trans*…A person with a trans body “build” their own identity. They “remap gender and its relations to race, place, class, and sexuality;” (ft.5)

Gordon Matta Clark (1943-1978) was an American artist known for his site specific artworks and his building-cuts. He approached the notion of deconstruction literally by creating his pieces from their destruction. He perceived the act of demolition as an opposition to social conditions or restrictions* .

This liberating process of undoing a building, undoing a gender, undoing an identity and inviting a culture to walk towards this path triggered my own practice as well.

In my case I try to unbuild my identity and deal with the uncertainty and excitement of destruction.

Personal artistic practice in conjuction with literature.

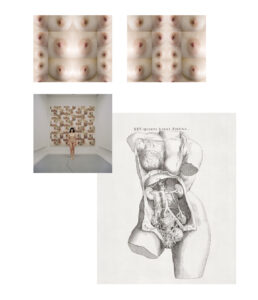

I used distance to observe the stages of my practice and I saw a shift from the costume of womanhood to the body. Reading the artist’s Laura Gibellini exposition, A Place Constructed , my attention was captured by the phrase the Place…takes place as an event: it is something one happens upon, it is a moving target, an achievement in progress.(ft.6) This phrase lead me on the parallelism with social identity. The identity as a place constructed on the prior ground of the human body. Our body is the primal material our very first identity that is given to us at birth and carries our sex and race which later on the social layers start to build on the top of them.

I started working on the body and I ended up in a visual discourse with the female breast and my body as the ground of this exploration. During this process I came across Philip’s Roth novel The Breast, a surrealistic narrative based on the Kafkaesque transformation of Mr. Kepesh into a six foot mammary gland.

It is a humorous provocative novel with a character trapped in an unwanted body. A claustrophobic situation with no given hope for ending by the author. I saw a parallel with my practice and I saw both me and Kepesh dive and get drowned into the flesh, losing control and surrendering to its impetus. It was liberating and suffocating at the same time.

Comparing mine and Roth’s path towards the breast regardless of our sex and gender, I see a body part which becomes an entity itself detached from the human body. I wonder how much it could take over ones identity and how it could be shifted or shaped. In Roth’s novel the breast is Kepesh’s nightmare, a bad hormonal joke. In a night he loses his body along with his identity. He is automatically transformed into a freak.

In my visual narrative though the breast is presented under a different concept yet it is still a provocative existence.

When I started working on my subject I did a few experiments with viewers from my inner social circles — which by chance are quite varied.

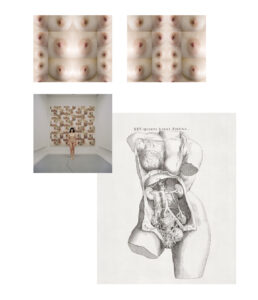

I photographed my breast, enlarged and printed it, creating a collage/background of gigantic nipples and breasts and placed them on my bedroom wall. I put my nipple in a frame and hung it on the wall, and later I photographed it as an installation. I also made a collage and took a self-portrait in front of it. Some of the viewers felt abjection, some liked it and others found it to be just too much.

But what exactly activated each of these feelings when viewing my installations. Everybody has seen breasts, big, small, in real life or printed in magazines, posters or art pieces. Is it the unfamiliar representation of them that brings the discomfort? Do they lose their identity? Do they become monstrous?

What I understood in the first place is that the breast had become anti-erotic and unpleasant.

I liked this aspect.

Inspired by Gordon Matta-Clark whose knowledge of building lead him to “unbuilding” and since I was working for many years as a photographer “building” appealing images, I was keen on the idea of breaking the viewers pleasure.

But I was not really aiming to shock them, mostly to poke them.

I went through the breast’s history and the way our notions have been shaped. I stripped the layer of “social clothes” and tried to see it naked and simple, just as a “mammary gland”. Afterwards, I created fictional images.

As I mentioned in the first chapter, photographing my self equals to giving up on a part of me. My interest to the social identities and female gender came from the need to understand my placement on society and get rid of any pattern that repress me. I do not know yet if I managed through my work to deconstruct the identity of my female body but I know for sure that I feel much lighter after this process!

Footnotes

01. loosey-goosey is the way that J. Halberstam calls herself when it comes to the choice of his pronouns (http://www.jackhalberstam.com/on-pronouns/)

02. Interview with Elina Brotherus for the exhibition “It’s Not Me, It’s a Photograph” at KUNST HAUS WIEN (March 14 – August 19, 2018) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WrvtCrJH6_o)

03. Butler, Judith, (2011). Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. Routledge. p.5

05. J Halberstam (2018), Unbuilding Gender, Trans* Anarchitectures In and Beyond the Work of Gordon Matta-Clark (https://placesjournal.org).

06. Gibellini Laura. A Place, Constructed (JAR paper)

Illustrations

All of the displayed images belong to Katerina Tsakiri and are part of the process and the final material of the work I Climbed Across My Two Little Mountaintops.