Portraits of High Places: Conversations With the Fairies

“Why on earth am I photographing a mountain?”

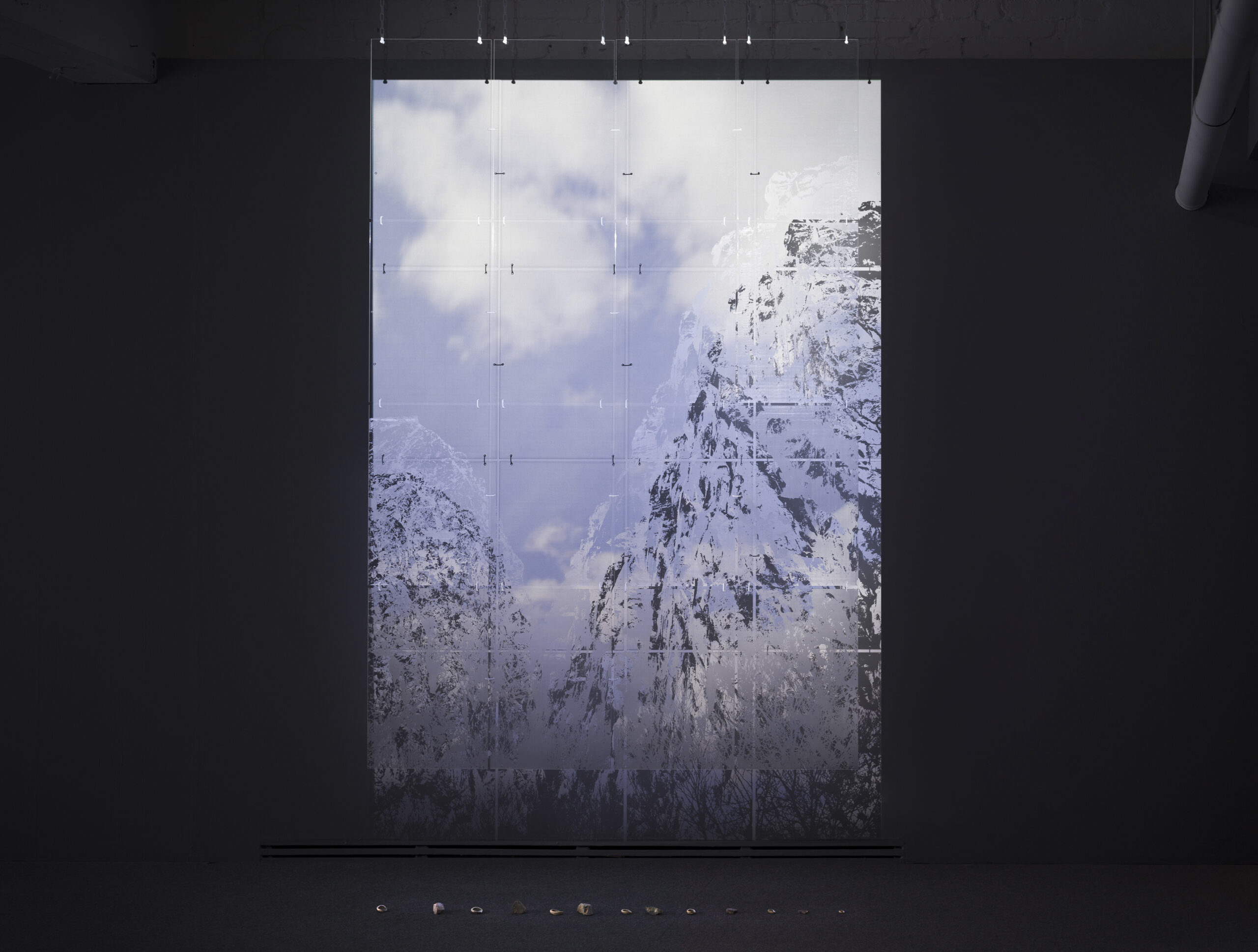

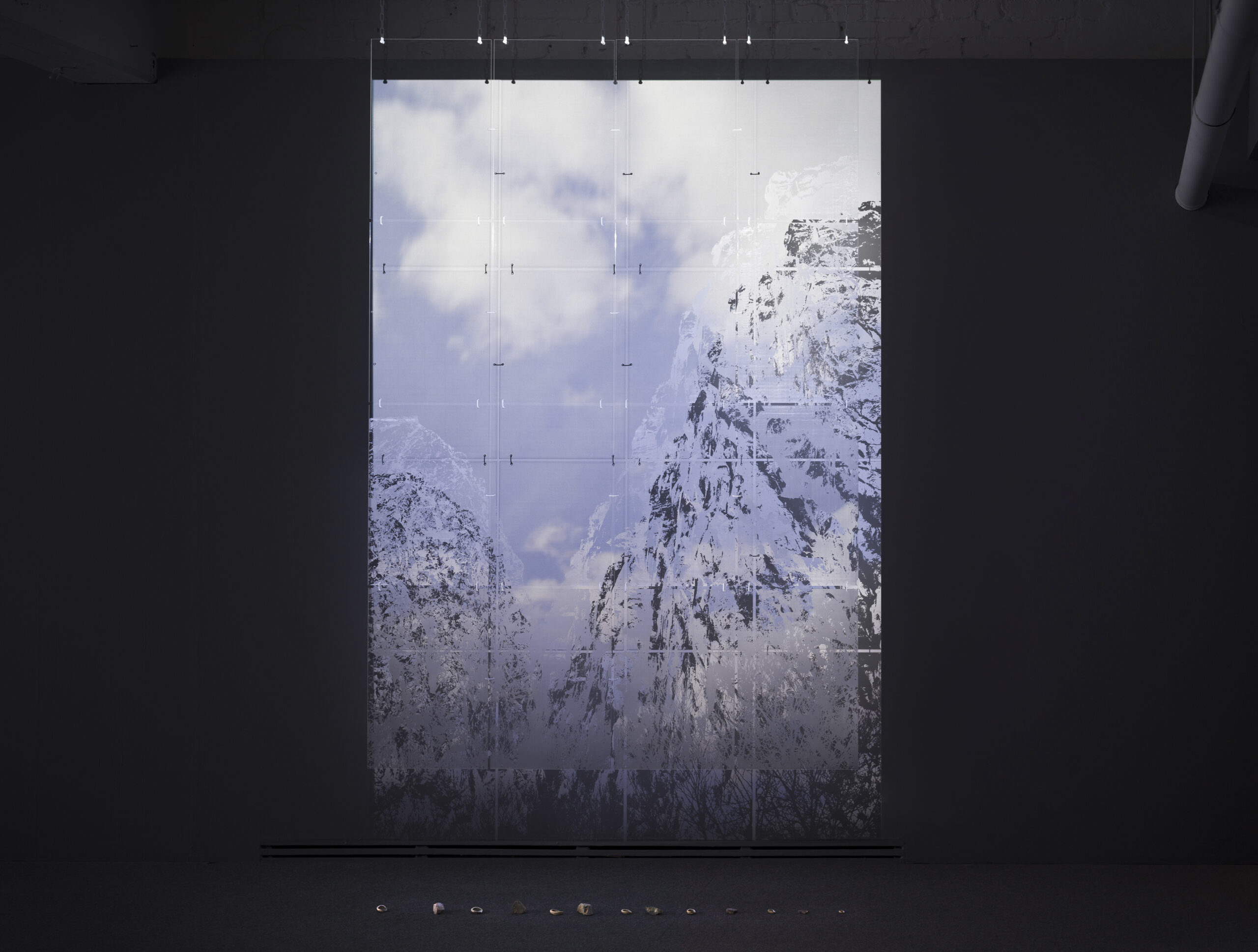

I’m standing outside on the deck of the ferry from Rab to Stinica, breathing in that salty sea breeze, The sky is blue and the sun feels warm against my skin. Two weeks have passed since I arrived at Vidova Dorica, to the family house under the holly oak. The small house hidden behind olive groves and fig trees. On the island where I have spent many summers together with my father. Biking through pine tree forests and diving in clear blue waters. I’m just about to walk back to the car deck, while Velebit grows before my eyes. That special feeling spreading inside me as I glance over the Adriatic Sea, up towards the bold formations of the mountain peaks. Velebit stretches along the coast, framing the lively waters. The pungent rocks and the lack of vegetation giving the mountain a solid facade. The strong sunlight casts shadows that land along this solid surface of the mountain, adding to the dramatic vision that resides, there on the mainland. Clouds slowly floating around the mountain, like lost souls searching for memories of times that passed. The closer I get to the coast, the better I hear the sound of the cicadas’ as their song becomes clear. Constant and pervasive.

…

– Oh Velebit, the rocks of the fairies’. Where are you hiding?

– Are you flying among the misty peaks? Or, perhaps you transformed into clouds.

…

I imagine “the room” as the photography itself, i.e. what exists between me and the mountain. The meeting between us, illustrating a process of something that happens which is not always easy to describe with only words, but possibly together with the camera. Then I reflect upon those many photographs there must already exist of this mountain. Or of mountains in general. I’m thinking of what Roland Barthes writes in Camera Lucida about how photography mechanically repeats something that will never occur again. I wonder how that thinking process works in relation to a photograph picturing something as consisting as a mountain: Something which historically has and most likely will remain nearly unmodified. In other words, a landscape that seems permanent. So, how come that I’m again standing here with my cameras? How can I be fueled by such wonder and reverence, driven by the mere sight of this landscape? What is my relationship to this mountain and what do I wish to get right, along with my camera?

…

– Vila Velebita, the creatures of the air and heavens, I followed you and now I’m lost.

– Last night as I lay sleeping I thought I heard you call my name.

I set the focus and hold down the shutter

”Click”

…

When I photograph Velebit I think of the mountain as a place, but also as a figure of constant presence. This is one aspect which particularly affects my photography more than I would think: Me seeing the mountain as if it were another person. Similarly to the unpredictability I find in another human being, may the mountain also overpower me with capricious winds and sudden thunderstorms. The difference is that almost every time I’m photographing another person, I find an uncomfortable feeling in my body. A feeling I don’t have when photographing landscapes or other subjects that do not look me straight in the eyes. Or rather, straight through the camera eye. I have always found it easy to get in touch with my own feelings through an actual place. Especially a place that holds so many of my memories, which connects me to my background and the family history.

…

– Vila Velebita, where did you go?

– Can you tell me about the past? Or will you show me what the future holds?

…

A man once told me he saw a fairy through his window at the slopes, behind his house. When he opened the door and went outside to take a closer look, she was gone. On the spot where she sat there were traces of her presence in the grass. Myths and legends have had different functions throughout history, frankly they still have today. Among others, they have been used to warn, or to foreshadow something that is about to happen, but also to witness something that has happened. Historically, we’ve been using these types of stories for a long time, long before the photograph itself. I thought of the collective memory of these myths, especially those concerning the mountain range which I stand in front of in this very moment. The myths preserved in both text and the folklore, but not yet much in photographs.

The photographer Ansel Adams devoted much of his time to depict mountains and a reviewer once wrote that Adam’s photographs resemble portraits of those massive rock pieces, which in turn seem to be inhabited by mythical Gods. While standing below the cliffs of Velebit, when the light is just about to set, my surroundings become almost spellbinding. I think of what Adams once called his ‘visualization’, i.e. not what his eye, but the inner lens of his imagination could see. His intention was to transmit the mountains emotional quality onto the photograph itself and he knew exactly how he wanted the actual print to look like. There was a moment when the light was failing him and he was down to only one or two glass plates. He then came up with the idea of using a deep red filter to turn the sky in the photograph almost black, which created a great contrast between the snow and the mountain. His decisions resulted in one of his most admirable photographs called Monolith, the Face of Half Dome.

…

The sun is about to set, as I turn my camera towards the shimmering heights.

– I heard you singing below the rocks as the sun went down.

– I think saw your beautiful hair, flowing in the swaying wind.

”Click”

…

…

It’s getting dark and through the lens I see the contours of the mountain in soft moonlight.

– The night-wind rocks the bellflowers to sleep and I can hear your footsteps by the opening of the cave.

– Vila Velebita, I will leave you now, knowing that we will meet another time.

“Click”

…

Literature:

Alinder, Mary Street. Ansel Adams, an Autobiography. 1st ed. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1996.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. 2nd ed. New York: Hill & Wang, 1982.

Bergman, Linda. I August Erikssons fotspår. Verk. 2020-01-01. https://www.verktidskrift.se/i-august-erikssons-fotspr-linda-bergman (Accessed: 2023-01-18).

Brunnbauer, Ulf & Pichler, Robert. Mountains as “lieux de mémoire”. Balkanologie. Vol. 4, n° 1-2, 2002.https://journals.openedition.org/balkanologie/433 (Accessed: 2023-01-03).

LegendFest. Beings in Croatian folklore. LegendFest. https://legendfest.hr/en/festivals/folklore/ (Accessed: 2023-01-18).

Luck, Addison. Ecoperspectives Blog. Vermont Journal of Environmental Law. https://vjel.vermontlaw.edu/rights-nature-movement-closer-look-new-zealand (Accessed: 2023-01-18).

Stone, Christopher. 1972. Should Trees Have Standing? – Toward legal rights for natural objects. Southern California Law Review. Vol. 45, 1972: 450-501. https://iseethics.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/stone-christopher-d-should-trees-have-standing.pdf

(Accessed: 2023-01-18).

Solnitt, Rebecca. A field guide to getting lost. 1st ed. Edinburgh: Canongate Canons, 2017.

Unesco. Velebit Mountain. Ministry of Culture. 2005-02-01. https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/2013/ (Accessed: 2023-01-18).

W, Jilly. The Japanese concept of Ma. art design Asia. https://artdesignasia.com/the-japanese-concept-of-ma/(Accessed: 2023-01-22).