The Decisive Moment and the Encounter (in a new place)

Part 1(Introduction and thoughts on light and destruction)For photography and photographers light is both a source of creation and destruction. The very light that brings photographs into being, can also make them disappear, or in other words, destroy them. It’s a balancing act. Not too little or not too much light. That’s why photographers early on learn the basics of camera exposure.

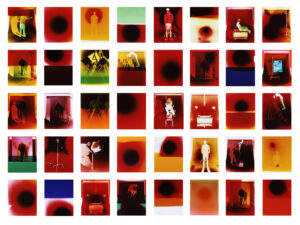

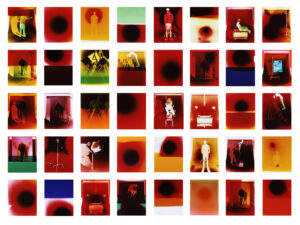

Light is active. It can be beautiful, it gives or “breathes” life and shape. It is usually a symbol for, or represents the good. But ironically light also has a dark side. It can be destructive, aggressive, and in fact, standing in the darkroom you’ll notice that it is intrusive. This duality, or paradox, is something I have worked with in my series Pause Between Thought and Action (2019).

When exposing too much light through a camera lens onto the negative or the sensor, the image then becomes lighter. In the analogue darkroom, it works the other way around. There I turn the space into a camera, adding layers of light during the print making process and the more light I expose, the darker the image gets. Every act of added creation demands the destruction of the original photograph and becomes a way to embrace the dual identity of our human nature, both as creator and destroyer.

As a more rather extreme example, which I’m also completely struck by, I could mention a work from Chris McCaw’s series Sunburns. For him, it started when he accidently left the lens of his camera open during a night shoot and captured the early morning sun and the intensity of the light burned a streak across his film. The images in the series sometimes look brutal, like someone cut through them with a knife.

After his burning accident, he started using paper negatives and deliberate overexposure to record a process by which light both records and destroys images.[i]

Part 2

(Accidents)

In 2016, during my bachelor studies, I was preparing for an exhibition that I was doing together with my Norwegian classmate Sofie Kjorum Austlid. Inspired by Wolfgang Tillmans’ Hasselblad Award exhibition in 2015 at the Hasselblad Center, our sincere ambition was to break conventions around photography. One important ingredient for us both, was that by doing the show together we agreed on losing a bit of control in the process of creating it.

One evening in the color darkroom, an unexpected event occurred that would come to be of importance for my future artistic practice and my attitude towards unplanned results and/or failures.

I was printing a photograph I took on Sicily a few years earlier. It showed my friend Camilla who is dancer, as she was stretching in a garden before a performance. I remember being fond of her pose, and her vertical body looking like one of the trees in the garden.

As usual, not to waste so much paper, I made some test strips and exposed them to light, trying different times and color filtrations. I made a few different exposures to have different versions of the same picture to choose from and then decide which one to go for.

Of the seven strips that I put through the ra-4 machine, only five came out the other end. I was too busy looking at those five strips, comparing their different hues and colors, that I forgot about the other two strips that had gotten stuck in the machine. It was about two hours later when a big print also got stuck that I took them out. They had somehow been folded inside the machine, after being developed and fixed and then gotten stuck in the drying section. I immediately wanted to open it up, to see the picture inside of the fold but when I did, I accidentally tore it apart, but luckily in the most beautiful way. It was an accident, but it seemed so perfectly arranged. A new shape appeared, similar to Camilla’s body. A new door had litterally opened and all of a sudden, I could not only in my mind, but also with my eyes, actually enter the paper.

The mistake quickly turned into what one would call an unforeseen or, most definitely, an unexpected result. Also, what was so striking was the simple fact that a destroyed piece of paper, something so ordinary and familiar (and worthless) became an unknown object which I felt completely drawn to. The mystery was obvious. In that moment I didn’t think about my choice of keeping the destroyed piece of paper as being an important decision, but now, five years later, I have understood that it has been a part of shaping the current way in which I work with photography.

Part 3

(Looking for the unknown)

A while ago I got deeply drawn to the color blue and it wasn’t just any type of blue, it was that Yves Klein kind of blue. I had discovered the magical world of Anna Atkins’ cyanotypes, which made me think of a beautiful blue and asymmetrically framed artwork, made by the artist Graham Collins. I saw it for the first time in the magazine Kennedy (Issue 4) some years back. Later I scanned the image and have had it saved on my computer’s desktop since then. I remember thinking that I would use the image as inspiration for something I would create in the future, but those vague ideas faded out and eventually I stopped giving it notice.

Until it popped up in my mind again.

It didn’t take me long before I found myself in the darkroom looking for that blue. It felt new and exciting being driven by the search of a color instead of a certain idea or concept, or a perfectly printed photograph. At the same time, I also knew that when I had found the particular kind of blue, the color in itself wouldn’t be enough. For some reason I remembered what happened to the print of Camilla that got stuck in the machine and I felt that I wanted to do something along those lines.

Could I somehow actively reenact what happened? I didn’t want to create a similar image, nor the exact same result, I just wanted to be surprised again.

In Rebecca Solnit’s book A Field Guide to Getting Lost, she’s confronted by a student of hers with a quote from what she said was the pre-Socratic philosopher Meno. It read,” How will you go about finding that thing the nature of which is totally unknown to you?”. [ii]

Basically, how do you look for something when you don’t know what you’re looking for? And if you find it, how do you know that what you find, is what you were looking for?

Working with chance and accidents as tools of creating I see a clear difference in losing control and actively getting lost within your process. In her book, Solnit writes about the method of getting lost on purpose, as a way of searching, an attitude and a way of being so utterly immersed in what is present so that its surroundings fade away. She refers to Walter Benjamin saying that, to be lost is to be fully present, and to be fully present is to be capable of being in uncertainty and mystery. [iii]

Now, looking back, reflecting on me wanting to be surprised, I would say that instead of creating a monologue I wanted to create a kind of dialogue. Me ”saying”, by creating the work of art, and the work of art itself ”saying” whatever it might want to say by having been created. Us communicating. Us being separated from each other. Both giving and receiving.

The American academic W. J. T. Mitchell suggests that pictures are not only vehicles of meaning and instruments of power, but expressions of desire. Instead of talking about what pictures mean he shifts the focus to what they want. The expression of want may not always be visible or in correspondence with what is depicted, it might manifest itself through absence, through what remains concealed. [iv]

By being a physical photograph, an object of this world, it could now, perhaps, have the ability to channel the invisible, the unknown. Referring to Mitchell’s text, I like to play with the idea that the photograph becomes the gateway through which the unknown and the invisible manifests itself. I immediately think about the story of Narnia and the wardrobe which mysteriously functions as the gateway to the unknown and the unfamiliar. A new world, or, an extension of the familiar world.

Even if it is a bit of a side track to what this article addresses, I think my interest in metaphysics and theology is worth mentioning. Growing up in a Christian family I was early on intrigued and confronted with questions around God, and from that, stems my curiosity towards the unknown. That curiosity is, I guess, partly expressed through my photographic works, and sometimes it even functions as the reason for my art making. There are of course also other reasons, one being the unbearable need to create which also gives an enormous amount of satisfaction.

I found the deep blue after exposing the glossy Fuji paper for 77 seconds with that perfect combination of yellow and magenta filtration. Before putting the 110×76 cm paper through the Ra-4 machine I folded it, hoping that the paper would stick to itself so that I could rip it open again. But it didn’t. Instead, when I opened the paper after having passed through all the chemicals, it smoothly unfolded and the surface which was still wet from the chemicals looked extra glossy.

To my surprise, the fold and the vacuum it created, made the chemicals not reach all parts of the paper. It created a horizontally mirrored abstract image, a photograph that didn’t seem to refer to anything but itself. It looked weird, nothing like what I had expected nor hoped for. Still I decided to try again, because it was something with its deep blue surface softly intertwined with nuances of green and its white undeveloped parts that I liked. I continued doing around ten of these folded images and they all came out very different except two that almost looked the same. I understood that how the paper was inserted in the machine effected the outcome of the abstract pattern.

I decided to put the two similar images next to each other so that they also mirrored vertically. And there it was, the result of the process and act of getting lost, and, – of the decisions made along the way. There in that moment, the world suddenly became larger than my knowledge of it.

I believe it is those decisions that do it. By creating photographs without the use of a camera, the moment of the ”click” is replaced by the decision, or decisions, made along the image’s coming into being.

In the process of getting lost one will sooner or later face a moment where the making of a decision is unavoidable. It may be when to interrupt and take control again, or to decide when it’s time to find one’s way back to the track. It requires some presence and sensitivity to be able to recognize the significance of these events.

In the end, it all comes down to the decisive moment, or moment of decision, in which one has to decide which piece of paper will stay and which will be thrown away.

Part 4

(The decisive moment, intuition, recognintion and the encounter)

Whether a practitioner or visual consumer, most people interested in photography are familiar with the concept of ”the decisive moment”.

For me, coming from a typical documentary photography background, the decisive moment has always been about being at the right place at the right time, or more accurately, pressing the shutter at the right time with the right shutter speed, catching that perfect moment. And of course, composition!

Even though my photographic practice looks a lot different now, I think that the concept and the idea of the decisive moment is still present, but, rethought and adapted to my present work. To clarify what the original thoughts behind the concept are, I turn to the source himself looking for an explanation.

In 1952 the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson proposed what would be one of the most highly debated and well-known concepts in the history of photography. The Decisive Moment is the English title of his famous photobook originally titled Images à la Sauvette (Images On the Run), published by Verve in France in 1952. [v]

In the preface of the book, in the chapter regarding composition, the reader is offered a text that deals with the idea of the concept saying that:

To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression. [vi]

As mentioned in the introduction, I don’t mean to directly apply the concept of the decisive moment associated with street-photography in this new context. Instead I want to use it as a point of departure in explaining my flow of navigating and negotiation through the moment of decision.

Recognition plays a key part in the moment of decision. But how exactly do I recognize what is good or not? I could simplify it and say that I just know, that it’s something that I just feel. And probably most people can relate to that when for example choosing the red sweater over the blue, it just felt right. There’s a quote by the photographer George Tice that tries to describe that:

“As I progressed further with my project, it became obvious that it was really unimportant where I chose to photograph. The particular place simply provided an excuse to produce work… you can only see what you are ready to see – what mirrors your mind at that particular time.” [vii]

In this last chapter I’d like to look into and try to explain the terms recognition and intuition from a philosophical and personal point of view. How does it work and am I even able to come near an answer? Is an answer always good? Take intuition to start with, which could be explained as the ability to understand something instinctively, without the need for conscious reasoning. A way of thinking-in-the-body. It’s close to what we commonly would call a gut-feeling, so maybe one could simply say that it’s about feeling rather than thinking. Intuition is something we react to, or act upon. In the moment of having to make a decision, intuition might be the actual decision trigger, taking you in either this or that known or unknown direction.

I guess there’s an assumption that acting intuitively would be the same as sloppy decision making. A lazy way of navigating through choices, taking chances. But I wouldn’t call that anywhere near “sloppy”, or not-really-knowing-but-doing-it-anyway. That sounds like how religious people sometimes are described, having a so-called blind faith. But I would instead argue that, as the Historian of ideas Per Johansson speaks of belief or having faith; that it can be seen as a deep intellectual intuition of the nature of existence. [viii] His definition stems from the book of Hebrews 11:1 in the New Testament where it says: “Now faith is the assurance that what we hope for will come about and the certainty that what we cannot see exists”. [ix]

One could even apply that to modern physics with its formulas expressing the laws of nature. We can’t see the laws of nature nor the mathematics behind the physical world but we strongly believe they explain why and how the physical world works. And all of a sudden faith and science doesn’t seem to contradict each other that much. I am in general not so interested in the dead-end zones of contradictions, but rather the areas in between them. The same way goes with art-making. I am more interested in issues of duration and process, and not starting-points or final results. Of course, I find it exciting the moment I’m struck by a great idea or when I stand in front of a finished artwork, but I’m more drawn to being in a state of transformation, being lost moving towards the unknown, being in suspense, which is also, in a way, being at risk. There’s a risk of failing and a risk of being disappointed. The doubt that it might not work out is also what makes the satisfaction so great when it actually does.

Risk. Yes, risks. I once read that love is a risk in the book “In Praise of Love”, by the philosopher Alain Badiou. After taking it up again, re-reading the introduction I was struck by his quotation from Plato saying: “Anyone who doesn’t take love as a starting point will never understand the nature of philosophy.”[x] In my mind I switched philosophy to photography and wondered if that could ever make sense.

But I’ve now come to settle my mind around the idea that love actually might be one way of describing the moment of decision and the moment of recognition.

So first, what is love? According to Badiou, love is, “in fact, anything from the moment our lives are challenged by the perspective of difference”[xi]. This would mean that love makes us see the world in a new way and it is within this challenge that the risk lays. Either you take on that challenge, take a chance and realize how enriching life all of a sudden gets, but that very difference can also become what threatens your view of the world, your truth. The perspective of difference is an unknown territory, an unknown perspective, because we have no idea what the world is like when it is experienced, developed and lived from the point of view of difference and not identity.

For this to even be an option two people must meet. What Badiou calls “the encounter” is when two people meet and start to experiencing the world in a new way. It often happens by chance, that we randomly meet someone interesting and exciting, but how can what is pure chance at the outset become the fulcrum for a construction of truth?[xii] To curb chance and to turn it into a process that can last, Badiou suggests that we repeat and endure.

The same question and answer go for making abstract images in the darkroom using chance as a tool of creating. At the moment of decision, the moment of recognizing if the image is good or not, maybe love is the answer. Maybe, through repetition, endurance and collecting experience, the moment of recognition is exactly like “the encounter”, in the way that the good image, the good work, somehow make you see the world in a new way.

Images:

Image 1: Images from the series ‘Pause Between Thought and Action’

Each 25 x 20cm

C-type prints.

Image 2: A tree, a girl, a decisive moment, 2016.

53,5 x 35 cm

C-type print

Image 3: Untitled I (Folding series), 2019.

155 x 110 cm

Collage of two c- type prints.

Refere

[i] Rexer, Lyle, The edge of vision, the rise of abstraction in photography, Aperture, 2013 (p.184)

[ii] Solnit, Rebecca, A Field Guide to Getting Lost, published in Penguin books 2006 (p.4)

[iii] Ibid. (p.6)

[iv] Mitchell, W.J.T., what do pictures want? The lives and loves of images, published by The University of Chicago Press, 2005.

[v] Published by Simon and Schuster (in collaboration with Verve of Paris), New York 1952.

[vi] Cartier-Bresson, Henri, The Decisive Moment, Published by Simon & Schuster in collaboration with Editions Revue Verve, 1952.

[vii] Sontag, Susan, On Photography, Penguin Classics, 2008, quote by George Tice (p.154)

[viii] https://sverigesradio.se/sida/default.aspx?programid=4462 (07-12-20)

[ix] https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Hebrews%2011&version=ISV (06-12-20)

[x] Badiou, Alain, In Praise of Love, Serpent’s tail, 2012, London (p.3)

[xi] Ibid (p.23)

[xii] Ibid (p.41)