Where do you store me?

She died almost 10 years ago. We were really close, and she was the only person in my family I felt a strong connection to. I even look more like her than my parents. After she died my mom found an envelope with photographs addressed to me. “To Emi. Only she understands art.” Her cheeky attitude made me smile. She always made me feel like we had our own secret society, and the rest were just stupid.

I hold a picture of my grandmother in my hands. She stares at the camera with defiance in her eyes, the same look she had whenever she told me stories about leaving Karelia. Her hair is gathered on the top of her head, tied together with a brown hair clip. We used to braid each other’s hair while watching Days of Our Lives on TV. Her hair was long and dark, rough, just like mine.

Looking at the picture I can almost feel the weight of her hair. Almost. I wish I could. My hands are just reminiscing something they used to feel. Like a copy of a memory, or a ghost.

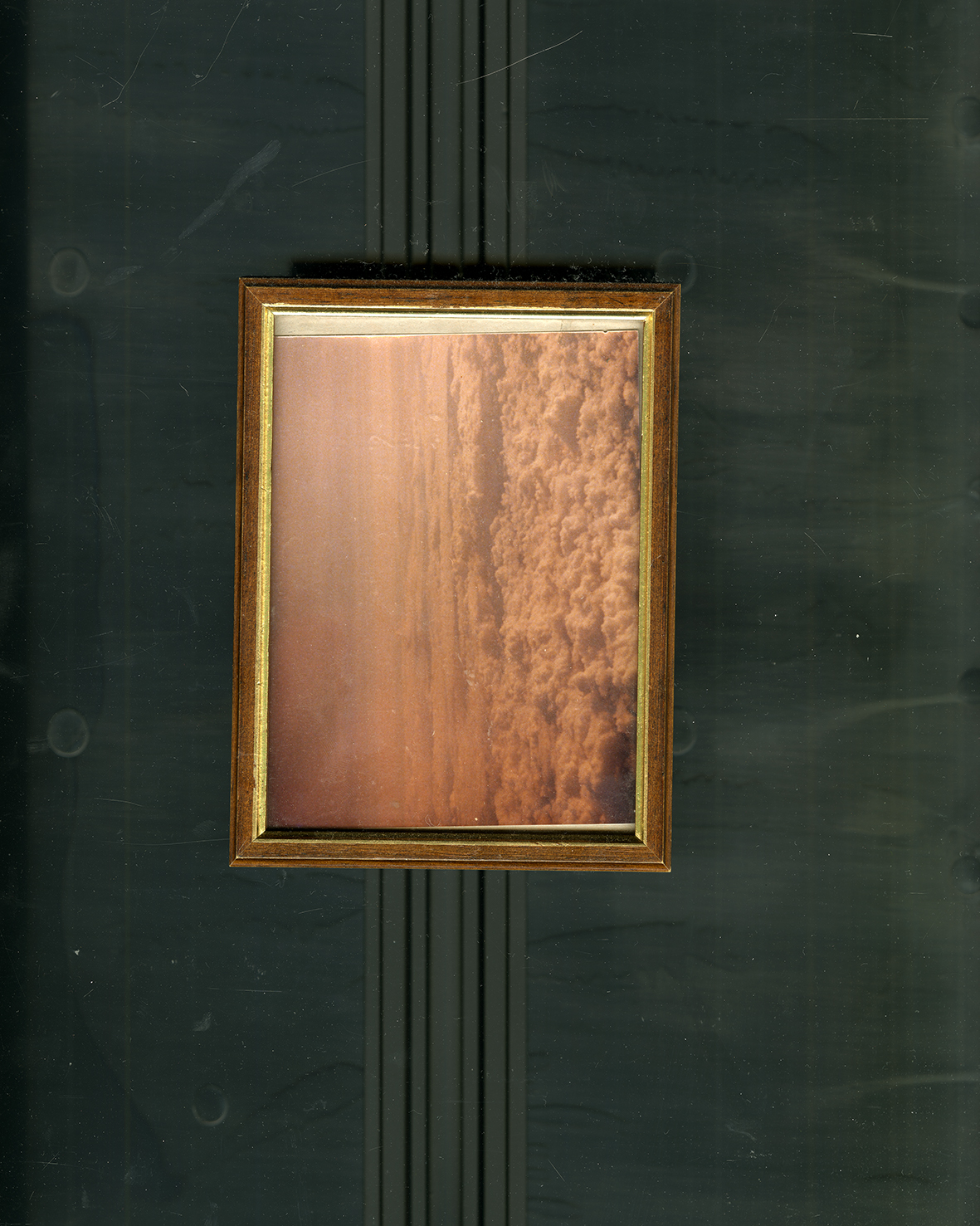

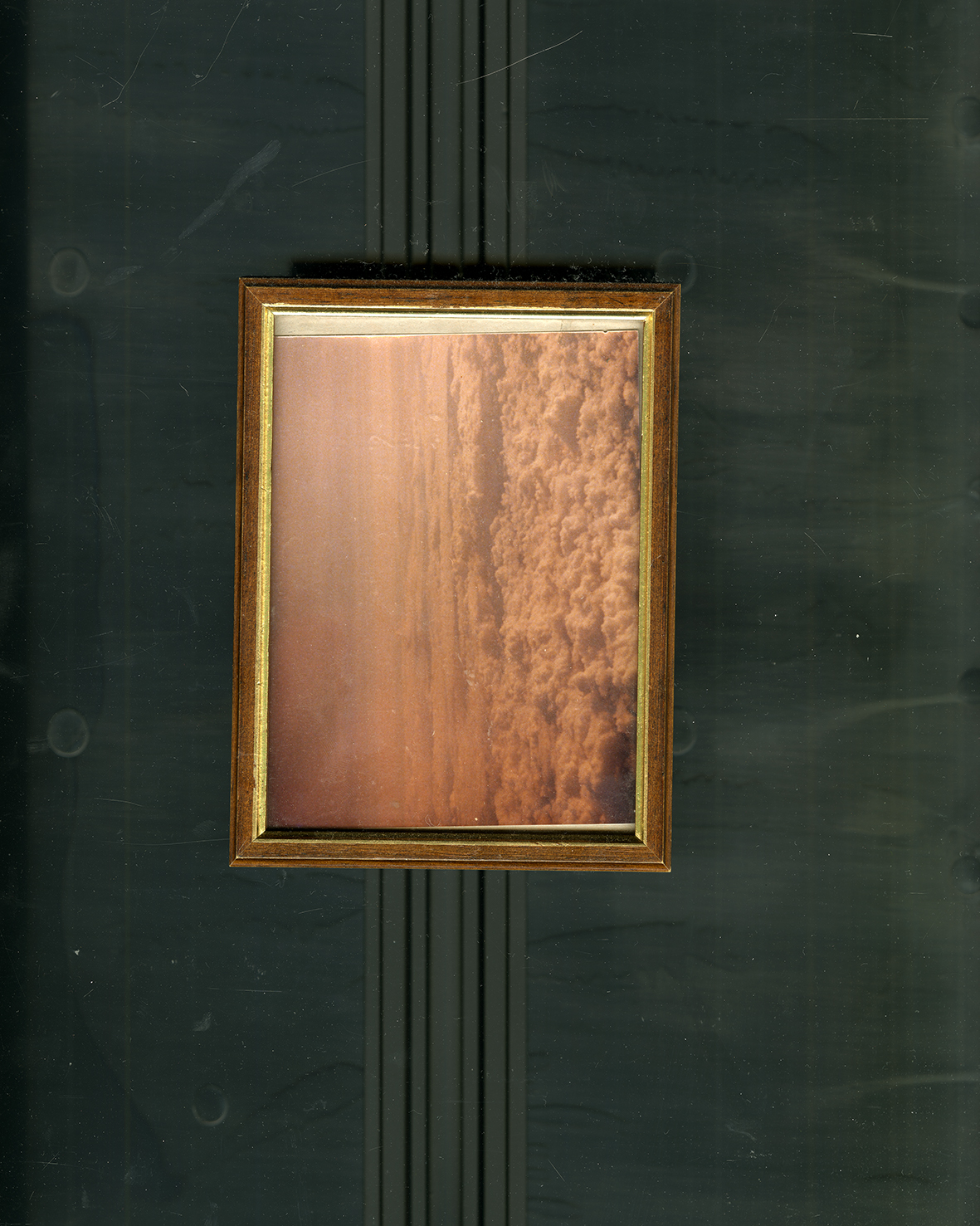

With photography there will always be a sense of distance. It captures something, but leaves out a lot too. Geoffrey Batchen speaks about breaking the distance with daguerreotypes accompanied by different elements, which open a deeper layer to the memory. The details not always experienced with eyes. Batchen refers to these as signifiers of memories.

In my grandmother’s case her picture would be mounted on a casket made of hand-painted porcelain. It would smell like it does in kitchens when you fry onions and mushrooms in butter. It would be installed under birch trees, in a forever partly cloudy place. It’s probably not how my grandmother would signify herself, but it’s me who holds the memory of her. The tiniest details create the memory. The kind of details one has little to no control over.

I recall a saying about dying twice; first in one’s physical body and secondly when one’s name is said aloud for the last time. The second death happens when the people holding the memory of the dead pass away too. Whose death will make me truly dead?1 In a way it’s kind of comforting. Us, humans, interlocked, creating clusters of remembrance, carrying parts of each other to different lifetimes. And, in a way, if dying twice, I guess one could also say we have two lives. The one that’s ours to live, and the other curated by people holding the memories of us. Susan Sontag states all photography to be memento mori, remembrance of our mortality.2 To take a photograph of someone is to participate in their mortality, act as a bare witness for the body they will from that moment on only drift further away from.

My grandfather was a photographer. I never got to know him – he stayed distant and separate from my life until his death. What was left of him, for me, is his photography, and some of his camera equipment. It is strange to examine someone’s personal photographic archive. It could have felt like crossing someone’s personal boundary, but seeing my grandmother in the pictures made me feel welcomed in. The archives consist of pictures of mundane but beautiful things – flowers, landscapes, views from bus windows, my grandmother… never himself. I found one picture of him, probably taken by my grandma, because there was a similar one of her. At least it seems to have been taken in the same place, with the same light. He looks uncomfortable in the picture. He is not looking at the camera, he is gazing at the ground in front of him, as though he was already making his way out of the shot. It stands out from the rest of the pictures, because it is a portrait of him. The only picture where he didn’t have all the control. The pictures revealed a side of my grandfather I never knew. Through his pictures he seemed like a soft, loving man. The man I (hardly) knew always sat alone in silence.

I wish I could have talked with him about his photography. I wish I could ask him what made him photograph, and what he thought was going to happen to his pictures after his passing. He must have thought about it. At that time everything was analog. All the pictures and negatives were left in their physical form, in their basement. He must have thought about it. Sometimes I play with the idea that he left them for me to find. We never had a relationship, but maybe this was his way of connecting with me, or with anyone. I just happened to be the one to find them. Maybe he photographed simply to have proof of his existence, even if he himself wasn’t visible in the pictures. Because when I look at his pictures, I think of him. I think of him even if it’s my grandmother in the picture. There are no photographs without someone taking them.

His photography changes the memory I hold of him. With his photography he curates the memory of him. It is creating a layer of him that didn’t exist to me before I found his archives. Here, of course, I place a great value on the objects he photographed – the new layer of him would be different if instead of beautiful mundane things he’d shot pictures of dead animals and trash cans, for example.

They are quite powerful, the photographs. Was he a soft, curious, loving man after all? Maybe he just didn’t know how to be a grandfather? No one cold hearted would shoot flowers their whole life, would they?

Beauty is always attached to mourning. The thing that makes the sad beautiful is the presence of mortality. The knowing of something ending makes it special, and acknowledging that makes one hold on to it tighter, cherish it, before letting go. Obviously, many things that are sad are not beautiful in themselves. But what comes with the sadness of these things is always a wish for something else, better. Or a memory of what used to be. And in those lies the beauty. To grieve something is to say that something mattered, because its passing left a wound deep enough for us to feel a sense of loss.

I photograph, and always have, for this reason. The melancholic value. To possess the past, and to celebrate, remember and mourn the time lost. I think about my own death quite a lot. I used to be terrified of it, obsessive. Not knowing when, or how, made me insane. Not that I ever wanted to know, which made it even harder. I literally can’t know, not even if I wanted to. It could happen any minute now. Photographing makes me feel less worried about dying, at least the thought of it – as if I was more alive now. I imagine the way my loved ones would read me after my passing, would my work change the memory they hold of me? How they’d think of me?

Being insignificant. That fear has always been a thriving force in my work. I made a short film about the pain of being forgotten, Act of Violence. It consists of a moving view from bus window and a voice over reading a poem I wrote:

did it hurt? does it ever?

where do you store me?

did it hurt, does it ever?

how much memory did you have to erase to get rid of my eyes?

the opposite of love isn’t hate, it’s indifference

the absence of emotion

oblivion

the lack of caring

i’d much rather be hated by you

you see, hate is rooted in passion

you passionately hate someone

you wish them bad things, misery

you think about their stupid face

and the tone that drives you mad

how they move, and oh, how much you hate

they are everywhere

you give so much space for them to stay,

and burn the walls of your rooms

in some way you have to care,

to be able to hate that much

i’d much rather have you hating me really

because to be forgotten is an act of violence and it really hurts

so did it hurt you? does it ever?

to forget something is an act of violence

Being forgotten comes with the assumption of insignificance – if something is important, it’s on our minds. What is not important, we try less to remember. So eventually, we forget. Being forgotten by someone indicates lack of importance, significance. Being forgotten by someone states we are not enough to hold on to.

Maybe more than dying, everyone is scared of being forgotten? Living only once, while dying twice.

When thinking about the signifiers of my grandma’s memory, I can’t help but to think of mine too. We never see ourselves like others do. Would we recognize ourselves in the mind of someone else? Can the second life be curated?

1 Irvin D. Yalom

2 Susan Sontag, On Photography, 1973, p. 15